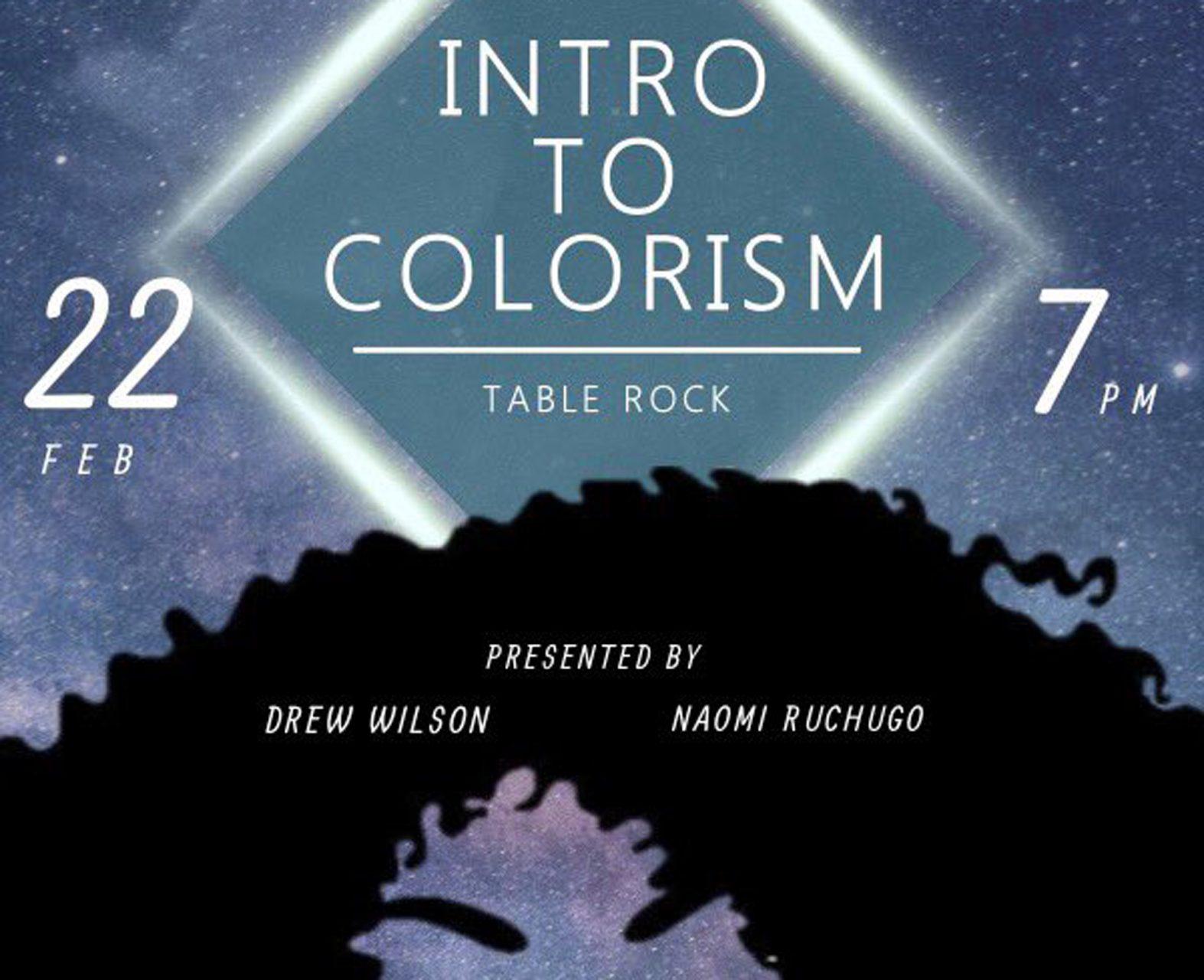

The Black Student Association and Minority Women’s Leadership Circle partnered with the Rho Theta chapter of the Delta Sigma Theta sorority to present a discussion on colorism at Plemmons Student Union on Thursday night.

The discussion, which focused on colorism in the black community, was presented by public relations major Drew Wilson and biology major Naomi Ruchugo. The talk covered the history of colorism, how it manifests itself in the digital age and how it can be addressed.

The Oxford Dictionary defines colorism as, “Prejudice or discrimination against individuals with a dark skin tone, typically among people of the same ethnic or racial group.”

In America, colorism acts as a sort of internalized racism that appears in the forms of implicit bias, stereotypes, microaggressions and media that have repercussions in interactions with strangers, friends and family alike, Wilson and Ruchugo said.

“Colorism penetrates every facet of our society, just like many other systematic, oppressive systems work in our lives,” Wilson said. “There was a study done at the University of Georgia that found that employers prefer light-skinned black men to dark-skinned black men, regardless of their qualifications.”

The presentation contained a poll where attendees texted stereotypes they had heard about light and dark-skinned people. The texts were collected in a server that compiled the results and entered them into a word cloud that highlighted the frequency of the most common stereotypes.

“There are obvious differences in the ways dark-skinned people are received and light-skinned people are received,” Naomi Ruchugo said.

Men are often subject to colorism through means like the Brute Caricature, which characterizes black men as animalistic, violent and threatening to society. The Brute Caricature was prevalent during Jim Crow and the Reconstruction Era, but is still often seen today. However, women face the brunt of the mistreatment, Ruchugo said.

“Colorism is enacted against black men, but it’s not on the same scale,” Ruchugo said. “And often times, we see colorism enacted against black women by black men. The intersection of colorism, misogyny and misogynoir where it pertains to black women is something I see a lot more, and that black men have the privilege of being men, meaning they still benefit from a patriarchal system as well.”

Colorism can also be particularly harmful in predominantly white areas like Boone, where there are fewer black people in general, but even fewer dark-skinned people, Wilson said.

“Usually, there’s power in numbers,” Wilson said. “But it’s hard to have power in numbers when there are such few numbers. Considering the fact that there’s 3.7 percent black people at this school, imagine the number of darker-skinned people who come here. It makes it harder for us to get by.”

Dark-skinned people are also often pushed aside in the media in favor of lighter-skinned people in order to appeal to whiter audiences, Ruchugo said.

“I think white people are more comfortable, when it comes to things concerning blackness, with lighter-skinned black people,” Ruchugo said. “Beyonce is a huge star, but we can’t deny the fact that Beyonce was in Destiny’s Child with two darker-skinned women, and she was the only person to go solo and be as big as she is.”

The talk ended with suggestions for addressing colorism in the black community, with ideas like starting a dialogue, making spaces for voices of dark-skinned people to be heard and rejecting the notion that light skin is better on any platform.

For those that are interested in learning about colorism but did not attend Thursday’s presentation, Wilson and Ruchugo will be leading the discussion again at Equity in Action on April 13 and 14.

Story by: Mack Foley, Intern Reporter

Photo courtesy of the Black Student Association