App State 90 years ago was very different from the university of today. For one, its population was much smaller.

According to 1940 census data, the town of Boone’s population clocked in at around 1,700 people. Today, Boone houses over 19,000 residents. Meanwhile, App State had 21,253 students enroll for the fall 2023 semester. In the very first issue of The Appalachian, dated Oct. 9, 1934, a cover story reported that a mere 913 students had enrolled that year.

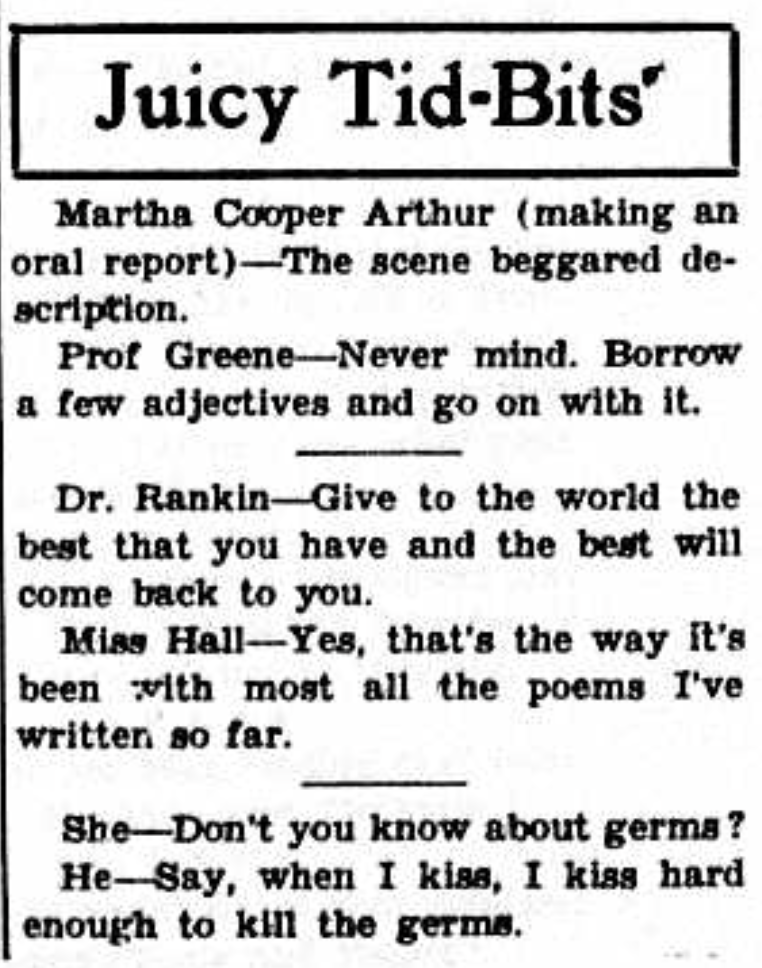

The duties of a newspaper for that tiny community of students focused on smaller scale events. Columns in old issues of the paper included a catty sense of humor. Perhaps the funniest pieces can be found in a feature called “Juicy Tid-Bits,” or pieces of hot gossip from around campus. The column brings the reader into the Teachers College classroom and the drama of the community’s halls.

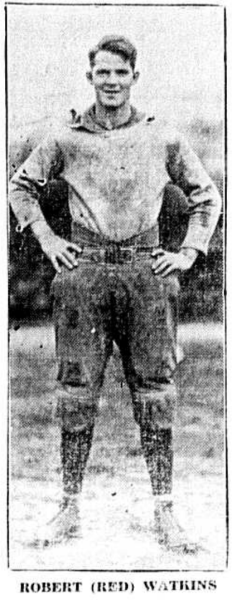

“Red Watkins wonders where Chinkapin Kendrick spent Saturday, Monday and Tuesday of last week –– and why she came in during the wee, wee hours of the morning,” one of the Oct. 9 tid-bits goes.

The Oct. 26, 1934 issue documents a particularly witty collection of comebacks and takedowns. In one quotation, Martha Cooper Arthur is making an oral report. “The scene beggared description,” she says. The juicy tid-bit kicks into action with Professor Green’s witty retort: “Never mind. Borrow a few adjectives and go on with it.”

The names of the students and faculty in the “Juicy Tid-Bits” column are given without context. The implication is that for readers of The Appalachian, the community that the paper served was small enough that the names alone would be completely recognizable. A similar effect can be found in Novella Dixon’s Oct. 26, 1934 column “Campus Tatlers,” where Dixon frequently references students by their first names alone. “Did you see Mac holding that baby Sunday? He does look ‘fatherly,’” one of her tattles reads.

The names of the students and faculty in the “Juicy Tid-Bits” column are given without context. The implication is that for readers of The Appalachian, the community that the paper served was small enough that the names alone would be completely recognizable. A similar effect can be found in Novella Dixon’s Oct. 26, 1934 column “Campus Tatlers,” where Dixon frequently references students by their first names alone. “Did you see Mac holding that baby Sunday? He does look ‘fatherly,’” one of her tattles reads.

Today, students turn toward social media for sharing juicy tid-bits of social information or funny classroom anecdotes. The concept of using a newspaper to do so is antiquated and charming, yet must have seemed bold and vital in those old issues.

Likewise, early copies of The Appalachian featured a full-page spread of clubs and their recent activities. This central hub of information for the 1930s resembles what an Instagram page or Engage email covers in 2024. For that small community, The Appalachian was the place to find new opportunities and shared hobbies.

Today, The Appalachian’s scope is much wider. While student clubs and academics remain the bedrock of its journalism, the focus of the paper is not merely for students about students. Instead, The Appalachian grants a perspective on the community at large from the point of view of its students. In recent years, the paper has covered everything from anti-semitism to local elections to major sports victories. There are feature pieces about community members, photos series of student and local life and national recognition for the paper’s reach.

There is a specificity to the early issues of The Appalachian that demonstrates an admirably tight-knit college town. The Appalachian was an outlet for a community already close together. In contrast, 2024’s paper serves as an inlet for a community that wishes to become more connected in an increasingly bigger world. Today The Appalachian focuses on the macro to bring people together on important topics and big events. Yesterday’s paper focused on the micro to bring students in on new opportunities and local happenings.

However, some things never change. There is a hefty section of the Oct. 9, 1934 paper devoted to college sports, including a photograph of “Juicy Tid-Bit” star Red Watkins. Watkins is revealed as the coach of the freshman football squad, something that would have been common knowledge to the students of 1934, but is a delightful example of campus community to a 2024 reader.

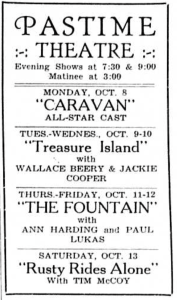

The early papers have advertisements for the Watauga Drug Store and since-demolished but familiar names like the Daniel Boone Hotel. The Pastime Theatre, which predates the Appalachian Theatre of the High Country by 14 years, listed showtimes and the bill of films coming to their screen. Alumni are referenced by local businesses. Current students are referred to the “Book Room,” home of “a full line of college stationary” among “cold drinks & confections.” The establishment may as well be an ancestor of the Campus Store and Market in Plemmons Student Union today.

Another similarity in The Appalachian of the past and the present is the coverage of performances and production in the community.

There is a lengthy segment at the end of the Oct. 9, 1934 issue about the upcoming third season of the Playcrafters, App State’s first student-run theater club, including a profile of their past productions. One notable accomplishment of those early Appalachian thespians was a production of the Ancient Greek sex comedy “Lysistrata,” performed in the spring of 1933 by the Playcrafters with a cast of 53 characters.

The arts were a unifying force for the paper’s readers then and now, as productions at the Schaefer Center, local Boone bands and App State theater groups receive regular coverage today.

The Appalachian was a different organization in its early days. The 1930s were a very different time. There is a specificity to the early issues of The Appalachian that demonstrates an admirably tight-knit college town. The Appalachian was an outlet for a community already close together. In contrast, 2024’s paper serves as an inlet for a community that wishes to become more connected in an increasingly bigger world. Today The Appalachian focuses on the macro to bring people together on important topics and big events. Yesterday’s paper focused on the micro to bring students in on new opportunities and local happenings.

The Appalachian was a different organization in its early days. The 1930s were a very different time. There is a specificity to the early issues of The Appalachian that demonstrates an admirably tight-knit college town. The Appalachian was an outlet for a community already close together. In contrast, 2024’s paper serves as an inlet for a community that wishes to become more connected in an increasingly bigger world. Today The Appalachian focuses on the macro to bring people together on important topics and big events. Yesterday’s paper focused on the micro to bring students in on new opportunities and local happenings.

However, it is a testament to the power of student journalism to unite a community that The Appalachian still stands nine decades later. While “Juicy Tid-Bits” may have moved other places, the importance of community at the heart of the paper has remained.