During the Boone Town Council’s March 19 meeting regarding the noise ordinance, Michael Hamilton, owner and operator of Boone Beats entertainment and sound engineering, measured decibel readings during the meeting on his smartphone as calibrated to the readers used by Boone Police.

As participants filed into the chambers, he came up with a reading of 70 to 75 decibels at its peak. If these sounds were to carry at the same levels to 10 feet outside of the chamber doors, the meeting would be in violation of Boone’s current noise ordinance, which was under discussion that night.

Boone has had a noise ordinance in some form for the past 12 years, but it has only seen serious dispute in the last few years due to vocal opinions from local late-night business owners who feel targeted by equally-vocal nearby residents with a tendency to call police and complain about blaring music, even when it isn’t in violation.

As a result, some businesses claim they have had to cut back on their musical acts while residents, on the other hand, claim they have had to down on sleep. Neither side thinks the current ordinance is working, although for entirely different reasons.

On March 19, the Boone Town Council motioned to vote in April on the possibility of adopting a modified noise ordinance that would raise the permitted decibel levels from 70 dB to 75 dB from 10 p.m. until 2 a.m. on Thursday, Friday and Saturday nights at downtown businesses that allow live and recorded music.

If these measures are approved at the April 17 meeting, Boone will enter a three-month trial period to evaluate its effectiveness.

This most recent conversation was sparked almost four years ago in response to residential complaints about the noise emitting to local properties from a mix of the bar scene and house parties in the downtown area.

Three years ago, the conversation took around 10 months to come to a vote with lots of committee input, said now-Mayor, then-Councilman, Andy Ball. He remembers around 60 local residents and business owners coming in public comment at the first meeting, and around 200 at the final vote, making the case for downtown businesses to have the ability to play music at a higher decibel threshold after other restaurants had closed.

“We ended up with something that was a little bit more strict than people wanted, but they had to realize at that point that they had a couple of advocates and they didn’t have an overwhelming majority of the council that felt there should be an exemption for downtown businesses,” Ball said, “because at the time we didn’t have the support of the council.”

Although not everyone was satisfied by the decision, it sparked a more narrow conversation with those most vocal with their complaints.

“They cited that it wasn’t people talking — it was music blaring, loudly,” Ball said. “And they discerned that it was live music.”

Before that point, there were no decibel levels in the noise ordinance. There was no regular police patrol and enforcement was strictly complaint based.

Police would come out to the site, determine where the noise was coming from and decide if the noise indicated that another code was in violation — occupancy limits or fire code — and write a citation for that.

Ball said that a policy like this cannot be adopted overnight, and instead calls for incremental change, as has happened since this issue was first introduced to the council in 2011.

“It was better than what it was, and without full support on council, that was all we could get,” he said. “I’m really proud of how far we got because it’s not something that’s so restrictive right now. It can be worked on.”

Ball said that from the beginning, this conversation has had a very specific focus: businesses that host live music in the downtown area. The key players on both sides made themselves apparent at the onset.

“… but it did take 10 months to figure out because nobody on the council, including myself, were noise experts,” Ball said. “We were not decibel-level experts, and figuring out how sound multiplies and gets louder, we weren’t familiar with that.”

Stephen McCreery, an assistant professor in the Department of Communication, who specializes in audio production, said that although these sound concepts are complicated, they are some of the only ways to clearly define levels of noise for purposes like law enforcement.

McCreery is also a resident of a downtown neighborhood, but has asked not to provide comments on his personal views of the ordinance.

When a sound is measured in decibels, it has to do not only with its actual volume, but also how loud we perceive a sound to be

The range of frequency of human hearing is between 20 hertz and 20 kilohertz — which is from very low in tone to very high. The higher the frequency, the decibels — or “loudnesses” — have a greater impact on what people might be able to hear at varying distances, because other frequencies don’t travel the same as those at levels.

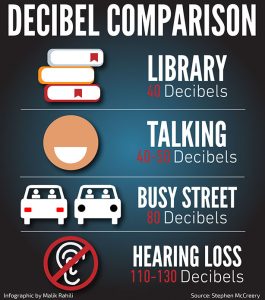

For example, McCreery said 40 dB is a quiet, muffled library atmosphere, 40 to 50 dB is normal or low conversation levels, 80 dB is what a busy street sounds like at a 10-foot distance, 100 dB is what most people would call loud, and 110-130 dB are entering the territory of what causes hearing loss.

Although these levels are clearly measured, McCreery says that when a sound is applied to the real-world, the decibel reading is not enough to determine how much a sound may be heard, and that some policies tend to downplay the importance of distance and geography in carrying a sound. Some frequencies travel farther than others at different rates causing a bigger and wider impact, and other people can hear more ranges of frequencies than others.

“In a situation where you have a downtown business that is facing north, and there’s a building directly across the street from it, that building is going to have a considerable impact to the sounds that are emanating from that building,” McCreery said. “A lot of those sound waves are going to be blocked and not be as audible on the other side of that building, if there’s a neighborhood or what have you, versus if that sound has a clear shot from the source to wherever it is you’re measuring that sound from.”

Midrange sounds, like those coming from an electric guitar or a snare drum, are going to be more directional than a low bass note, which tends to radiate in and out of a room. A standard-range pop or rock song is going to be more directional than low brass.

“This is why when you’re driving down a street and you hear somebody with their loud booming sound system in their car, you look around and you can’t exactly tell where it’s coming from,” McCreery said. “It’s the same principle.”

Boone measures sound with a directional meter measuring in dBA, which gives higher weight to sound frequencies that are going to be heard more by those in close proximity. Those are the sounds that cause the most issues, McCreery said, rather than higher and lower frequencies which are less audible even at higher volumes.

The dBA is a fairly standard measurement, and the only accurate way to measure a sound in the real world is like this, because what some call “volume,” although it may be standardized on amplification technologies, is ultimately subjective. Complaints, in any case, are based on perception, McCreery said.

“What sounds loud to me is not going to sound loud to you,” he said. “What sounds loud to you might sound very quiet to me, considerably.”

Different people have different ears, and some can hear more acutely than others. When the police or anyone takes a reading, they are measuring sound as it appears against the sound pressure levels of a source, comparing sound pressure to the ambient atmospheric pressure. The sound levels in Boone in the summertime may be standard amongst themselves, but could read completely differently at another elevation in the winter.

“As the sound pressure rises, we perceive a sound as being louder, because it is louder to us,” McCreery said. “Whether you consider it loud or not is a subjective opinion.”

The sounds that the AppalCART buses make — the periodic piercing hiss — would be deafening at close range but loses decibels at longer distances. Sounds in Boone may very well carry differently up through the valley to residential areas, but police readings until now have been taken from 10 feet outside of the business.

Stephen “Skip” Sinanian has owned Boone Saloon for 11 years. In 2011, his business began to receive citations about excessive noise from the Boone Police Department.

“I didn’t even know we had a noise ordinance,” Sinanian said.

He spoke with the chief of police only to discover that Saloon had a large number of complaints filed against them, although the town was supposed to contact each business with an issue with noise at the end of the year informing of them of their numbers, something that Sinanian said never happened.

He paid the fines and began speaking to the police and town council right around when the first revisions began. But after working with the town council for around eight months on the issue, Sinanian said some members became “draconian about it.”

So he sued the town.

“The ordinance was arbitrary and capricious, and like I said, kind of draconian, very severe,” Sinanian said.

He and the owners of Char — now The Local — filed the suit in 2012.

“[The lawsuit] sat around on some federal judge’s desk for nine or 10 months, and he eventually said ‘No, it’s legal,’” Sinanian said. “So we dropped the whole thing.”

Faced with no recourse, Sinanian has also had to nix many of his nationally touring musical acts from the venue as a preventative measure. As a result, his business dropped by 3 percent in sales between 2012 and 2013, a huge chunk of the standard industry profit margin of 3-9 percent.

“If you’re talking about dropping 3 percent, and your profit margin is only 5, then it’s more than a 50 percent of your profits that dropped — and that’s pretty much where I make my money,” Sinanian said.

It takes convincing for bands to come to Boone above other areas — it’s already hard to get the music here due to geography and tour schedules — but the issue of too much noise can turn bands away for good, even if restrictions do change at a later date.

“In the future, it’s going to be more difficult for me to reconnect with these incredible agents who have phenomenal culture that they want to share with Boone,” Sinanian said.

The band Future Islands was booked in Saloon just two years before they played on David Letterman’s show in 2014, gaining national recognition. Sinanian said that Boone has always been seen as a destination for some regional touring acts.

“Part of the town, what I think is a very small minority, wants to keep Boone in a china cabinet — to keep it dust free and the same forever — while everything else is going on around it,” Sinanian said.

Boone has always been known as a music town, he said. Sinanian moved to Boone from Atlanta in 2001 for the cultural and intellectual freedom on top of that. On this issue, he’s looking for recourse, calling the complaints humiliating and disreputable.

“I think the police are kind of confused – when they come here 45 times in two years, they have no idea,” Sinanian said.

When a business is not found in violation, responders are left with no other option, legally, than to keep checking in on complaints.

There’s a saying in the downtown music scene, Sinanian said: “Boone succeeds in spite of itself,” and that “a lot of the times the town is fighting progress,” he added.

Judy Humphreys and Terry Taylor live off Grand Boulevard in a residential area up the hill and two streets over from Boone Saloon, and have been the main voices to speak out in favor of more restrictive regulations.

Their residence is responsible for nearly all of the 48 calls to police regarding noise coming from a business in the past two years, 45 of which were directed at Boone Saloon, Boone Police Chief Dana Crawford confirmed at one of the public hearings.

Only on one of those occasions was Saloon found in violation of existing noise restrictions in 2014.

The couple has lived at their downtown residence for 35 years and never had any issues with the location until late night music venues began to really open up 10 or so years ago.

“Over a period of time it got to where there was enough aggravation that when the town said they were going to do something about it, I thought I needed to get involved,” Taylor said.

He doesn’t think that Boone as a whole is much busier or noisier from his days as a student at Appalachian — he doesn’t hear too much traffic or emergency vehicles — aside from the addition of late night venues.

Taylor wants decibel levels reduced at least another 5 dB throughout the entire evening, and to get rid of the complaint system in favor of a regular patrol.

“I think the police are capable of that decision,” he said. “They’re the keepers of the peace.”

His wife acknowledges the unique situation of their house and its geography within one of Boone’s oldest residential areas, but believes the businesses should be doing more.

“When I get in bed — and I never go to bed before 12:30 at least — and I call the police, which I hate to do because they have more important things to do with their time, they go to Boone Saloon and Boone Saloon always turns down the music,” Humphreys said. “I would think they should consider turning it down automatically around that time rather than have the police come on out.”

Paul and Marjon Zimmerman live nearby and say they can live with the restrictions as they are now, but hope they are not made more lenient without some sort of changes the businesses, such as the acoustics inside.

“There’s a fair place where we can all be happy,” Paul Zimmerman said.

He has lived a block from King Street since 1993, and said that the first noise ordinance was completely necessary in making the area, which is primarily student housing, more bearable to listen to on the weekends.

“Most college towns or cities that Boone might aspire to be more like have noise ordinances,” Marjon Zimmerman said.

She feels that a town needs businesses and people living nearby to visit and support those businesses, which are the main reasons why she likes living where she does.

“We can appreciate that there’s going to be noise from time to time, it’s just when it’s excessive,” she said. “If we can appreciate that, they should be able to appreciate [the fact that] it’s good for business to have people who live nearby as well.”

Paul Zimmerman agrees with his neighbors that their streets seem to exist in a strange “sound vortex.” Surrounded by vacation homes and student renters, he believes that those who are truly affected by the issue of sound appear strangely isolated in their residential neighborhoods because others may feel like they are in less of a position to make such a public comment.

Although others in the area may be experiencing the same thing, their circumstances might stifle their discontent, he said. For that reason, he thinks some of the outcry on the part of local businesses may be a little misguided.

“It’s not ‘stifling’ anything in Chapel Hill or Durham, with their noise ordinances — they’re thriving,” Marjon Zimmerman said, of the other locations taken into consideration by the town, some with more conservative ordinances than Boone has in strictly residential areas.

Judy Humphreys and Terry Taylor live off Grand Boulevard in a residential area up the hill and two streets over from Boone Saloon, and have been the main voices to speak out in favor of more restrictive regulations.

Their residence is responsible for nearly all of the 48 calls to police regarding noise coming from a business in the past two years, 45 of which were directed at Boone Saloon, Boone Police Chief Dana Crawford confirmed at one of the public hearings.

Only on one of those occasions was Saloon found in violation of existing noise restrictions in 2014.

The couple has lived at their downtown residence for 35 years and never had any issues with the location until late night music venues began to really open up 10 or so years ago.

“Over a period of time it got to where there was enough aggravation that when the town said they were going to do something about it, I thought I needed to get involved,” Taylor said.

He doesn’t think that Boone as a whole is much busier or noisier from his days as a student at Appalachian — he doesn’t hear too much traffic or emergency vehicles — aside from the addition of late night venues.

Taylor wants decibel levels reduced at least another 5 dB throughout the entire evening, and to get rid of the complaint system in favor of a regular patrol.

“I think the police are capable of that decision,” he said. “They’re the keepers of the peace.”

His wife acknowledges the unique situation of their house and its geography within one of Boone’s oldest residential areas, but believes the businesses should be doing more.

“When I get in bed — and I never go to bed before 12:30 at least — and I call the police, which I hate to do because they have more important things to do with their time, they go to Boone Saloon and Boone Saloon always turns down the music,” Humphreys said. “I would think they should consider turning it down automatically around that time rather than have the police come on out.”

Paul and Marjon Zimmerman live nearby and say they can live with the restrictions as they are now, but hope they are not made more lenient without some sort of changes the businesses, such as the acoustics inside.

“There’s a fair place where we can all be happy,” Paul Zimmerman said.

He has lived a block from King Street since 1993, and said that the first noise ordinance was completely necessary in making the area, which is primarily student housing, more bearable to listen to on the weekends.

“Most college towns or cities that Boone might aspire to be more like have noise ordinances,” Marjon Zimmerman said.

She feels that a town needs businesses and people living nearby to visit and support those businesses, which are the main reasons why she likes living where she does.

“We can appreciate that there’s going to be noise from time to time, it’s just when it’s excessive,” she said. “If we can appreciate that, they should be able to appreciate [the fact that] it’s good for business to have people who live nearby as well.”

Paul Zimmerman agrees with his neighbors that their streets seem to exist in a strange “sound vortex.” Surrounded by vacation homes and student renters, he believes that those who are truly affected by the issue of sound appear strangely isolated in their residential neighborhoods because others may feel like they are in less of a position to make such a public comment.

Although others in the area may be experiencing the same thing, their circumstances might stifle their discontent, he said. For that reason, he thinks some of the outcry on the part of local businesses may be a little misguided.

“It’s not ‘stifling’ anything in Chapel Hill or Durham, with their noise ordinances — they’re thriving,” Marjon Zimmerman said, of the other locations taken into consideration by the town, some with more conservative ordinances than Boone has in strictly residential areas.

Ball first heard responses from the public following the initial decisions during his time as a councilman in 2011 when he saw his contact information on a concert poster in a local bar.

The issue and its connection to local culture encouraged support from people who might not otherwise get involved with local government. He received more than 100 emails and was approached by people in the grocery store, restaurants, bars and coffee shops.

Today, the scene is much like it was back then.

“People ask me, ‘What are we going to do about the noise ordinance?’ and I say, ‘What do you mean? What do you think we should do about it?’” Ball said.

As the main proponent in favor of higher levels before the last vote, Ball has seen the effect on local businesses and music offerings, and has not changed his stance.

“Does one household’s enjoyment outweigh a business’s opportunity to provide live music? It’s a question that the town council is going to have to answer,” he said. “That’s a tough question.”

At February’s town council meeting, the issue was brought to public discussion.

Mike McKee, a professor of economics at Appalachian State University, spoke at the open forum and pointed out that being quiet may encroach on someone else’s business, and in such a case the town has waivers that exist to excuse the university’s football and marching band events from these same restrictions.

“These venues are putting on the music not necessarily because they want to provide charity to local musicians, but they’re making money while doing this,” McKee said. “That loss of revenue means there’s less money flowing into the local economy.”

The multiplier for that sector, in this economic region, is 1.5 to 1.6, McKee said, meaning that for each dollar that is spent in downtown Boone and circulates throughout the town, it returns in around $1.50 of value, as more local jobs are created and sustained, and those working in town re-circulate their money back into the local economy.

“I live in the local economy and came here mostly because of the entertainment sectors that were offered in Boone, that’s my own personal preferences,” McKee said. “The bottom line is that we are going to end up hurting the local economy if we keep tightening regulations.”

Councilman Fred Hay, who drafted the change in question, said he grew up near James Brown in Florida, in a town with a “little bible college,” noting that even there the noise policing was less restrictive than it is in Boone, which he claims attributes to some of the then local musician’s success.

“None of that would have happened if they had this noise ordinance,” Hay said. “Turns out he has become one of the most influential musicians of our time and I would hate to be on this council and do something that might prevent that here. Boone has potential.”

In February, the legislation was written — but not agreed upon — to raise levels to 75 decibels until 2 a.m. all nights of the week, as well as discredit the calls of any one residence to file more than three or five invalidated complaints against any one place of business.

The latter half, intended to deal with situations like that of the Humphreys and Taylor residence, was thrown out at March’s meeting after dispute from councilmember Lynne Mason, who said simply limiting excessive complaints was not an objective approach to the issue.

Mason cited the town’s stated mission in the proposed draft of the ordinance, which stated that Boone strives to encourage downtown activity, while also ensuring reasonable levels of quiet during “time periods during which many of the residents are customarily at rest or have an expectation of peaceful enjoyment of their residence,” according to the ordinance.

“I’m trying to find what that balance is because I don’t think there’s any dispute that we want a vibrant downtown,” she said during March’s meeting. “We want live music and all of that, and I mean that sincerely to everybody here.”

Although a proposed three-strikes rule would work against those who disagree with the current ordinance, Mason said even the act of increasing the threshold from where it is now already discredits those who complain against the existing levels. Instead, she proposed a three-month trial period once any change is adopted.

“I want us to do the right thing that will foster this vibrant downtown, but also figure out how do we protect the integrity of our neighborhoods and the livability,” she said.

McKee again warned against restriction as a limiter on Boone’s future success, noting that from an economic standpoint, a diverse set of business types, even in the same category, increases revenue for the town as a whole.

“If you have a range of entertainment options in a downtown area, people will come to town to take advantage of those options, even if they don’t utilize that whole range every time, the option value brings people in,” McKee said.

Like a shopping mall, customers need options to draw them to an area, he said. Nicole Kinnamon, co-owner of Speakeasy Tattoo Co., agreed.

“We would like to keep the music on the mountain so that we can keep our money on the mountain, and from there the town can succeed as well,” -Nicole Kinnamon, co-owner of Speakeasy Tattoo Co.

Modifications were agreed upon to draft legislation intended to raise the permitted decibel levels from 70 dB to 75 dB from 10 p.m. until 2 a.m. on Thursday, Friday and Saturday nights at downtown businesses that allow live and recorded music. If this is approved at the April 17 meeting, Boone will enter a three-month trial period and revisit the issue at a later date to check in.

“Does one household’s enjoyment outweigh a business’s opportunity to provide live music? It’s a question that the town council is going to have to answer,” he said. “That’s a tough question.”

At February’s town council meeting, the issue was brought to public discussion.

Mike McKee, a professor of economics at Appalachian State University, spoke at the open forum and pointed out that being quiet may encroach on someone else’s business, and in such a case the town has waivers that exist to excuse the university’s football and marching band events from these same restrictions.

“These venues are putting on the music not necessarily because they want to provide charity to local musicians, but they’re making money while doing this,” McKee said. “That loss of revenue means there’s less money flowing into the local economy.”

The multiplier for that sector, in this economic region, is 1.5 to 1.6, McKee said, meaning that for each dollar that is spent in downtown Boone and circulates throughout the town, it returns in around $1.50 of value, as more local jobs are created and sustained, and those working in town re-circulate their money back into the local economy.

“I live in the local economy and came here mostly because of the entertainment sectors that were offered in Boone, that’s my own personal preferences,” McKee said. “The bottom line is that we are going to end up hurting the local economy if we keep tightening regulations.”

Councilman Fred Hay, who drafted the change in question, said he grew up near James Brown in Florida, in a town with a “little bible college,” noting that even there the noise policing was less restrictive than it is in Boone, which he claims attributes to some of the then local musician’s success.

“None of that would have happened if they had this noise ordinance,” Hay said. “Turns out he has become one of the most influential musicians of our time and I would hate to be on this council and do something that might prevent that here. Boone has potential.”

In February, the legislation was written — but not agreed upon — to raise levels to 75 decibels until 2 a.m. all nights of the week, as well as discredit the calls of any one residence to file more than three or five invalidated complaints against any one place of business.

The latter half, intended to deal with situations like that of the Humphreys and Taylor residence, was thrown out at March’s meeting after dispute from councilmember Lynne Mason, who said simply limiting excessive complaints was not an objective approach to the issue.

Mason cited the town’s stated mission in the proposed draft of the ordinance, which stated that Boone strives to encourage downtown activity, while also ensuring reasonable levels of quiet during “time periods during which many of the residents are customarily at rest or have an expectation of peaceful enjoyment of their residence,” according to the ordinance.

“I’m trying to find what that balance is because I don’t think there’s any dispute that we want a vibrant downtown,” she said during March’s meeting. “We want live music and all of that, and I mean that sincerely to everybody here.”

Although a proposed three-strikes rule would work against those who disagree with the current ordinance, Mason said even the act of increasing the threshold from where it is now already discredits those who complain against the existing levels. Instead, she proposed a three-month trial period once any change is adopted.

“I want us to do the right thing that will foster this vibrant downtown, but also figure out how do we protect the integrity of our neighborhoods and the livability,” she said.

McKee again warned against restriction as a limiter on Boone’s future success, noting that from an economic standpoint, a diverse set of business types, even in the same category, increases revenue for the town as a whole.

“If you have a range of entertainment options in a downtown area, people will come to town to take advantage of those options, even if they don’t utilize that whole range every time, the option value brings people in,” McKee said.

Like a shopping mall, customers need options to draw them to an area, he said. Nicole Kinnamon, co-owner of Speakeasy Tattoo Co., agreed.

“We would like to keep the music on the mountain so that we can keep our money on the mountain, and from there the town can succeed as well,” -Nicole Kinnamon, co-owner of Speakeasy Tattoo Co.

Modifications were agreed upon to draft legislation intended to raise the permitted decibel levels from 70 dB to 75 dB from 10 p.m. until 2 a.m. on Thursday, Friday and Saturday nights at downtown businesses that allow live and recorded music. If this is approved at the April 17 meeting, Boone will enter a three-month trial period and revisit the issue at a later date to check in.

“In Boone we’re such a tight-packed community. We have one central business district and several neighborhoods above on the hills that surround it that the echoing effect comes up over the hills,” Ball said. “We have an interesting situation that may not have a good solution.”

He said that the ordinance is a good thing to have in any town like Boone, but that having lived downtown and in close proximity to bars for seven years himself, Ball knows that some of the noise just comes with the territory.

“Of course things bother you occasionally – it’s mostly people in the neighborhood making noise – but I heard the bars occasionally,” Ball said. “But you’re downtown, and that’s the price you pay for being downtown, for the convenience and the proximity you realize you’re going to have a little bit of a disturbance now and again.”

Sinanian said he doesn’t have time to wait around for the ordinance to keep changing, and may have to sell his equipment for more tables if it leads to his live music becoming less of a viable option.

“I like live music, but it’s not why I go out,” he said. “I bring it in here because it’s a small town, and this is the culture of the times.”

Sinanian said he’ll continue to bring the music to Boone Saloon

“I’m bringing it in for the kids, for the culture, for the people — for everyone who comes in,” he said, “and they come in over and over and over.”

Article By Lovey Cooper

Videos by Jackson Helms

April 2, 2015