The Town of Boone will install textual panels throughout the Boone Cemetery to educate visitors on the cemetery’s history.

The project is moving forward despite a monthslong conflict between town officials and a group of locals and descendants of historic families, who claim the original panel drafts included defamatory historical inaccuracies and exaggerated the cemetery’s racial segregation of white and Black burials.

The panels were drafted by the Historic Preservation Commission, a town body that works to “promote, enhance and preserve the character and historic landmarks or districts in the Town’s planning area,” according to the town website. In July, the HPC finalized drafts of four panels that interpreted the cemetery’s general history, racial segregation and Union grave burials.

After vehement criticism from the disapproving group, the HPC continued revising the panels until November, when the commission and town council approved final drafts for construction.

Eric Plaag, town council member and former chair of the HPC, authored the drafts but implemented suggestions from commission members throughout his research and writing.

1850s-1950s

Boone Cemetery origins and use

Sitting between Howard Street and App State’s East Campus, the Boone Cemetery is as old as the town itself, with its first burials happening at least 150 years ago.

During its use, the Boone Cemetery was segregated, with the west section reserved for white burials and the east for Black burials. While engraved headstones denoted most graves in the white section, burials in the Black section, including members of the Junaluska community, went largely unmarked.

“Under the economic realities of systemic racism, finely carved monuments

marked graves in the west section, while flagstones marked most east section graves if they were marked at all,” read the original draft for Panel #3.

The land began as the Councill cemetery and was originally owned by Jordan Councill Sr., a wealthy merchant who settled in Western North Carolina in the early 1800s before Watauga County and Boone were established, according to the 1915 book “A History of Watauga County, North Carolina” by John Preston Arthur.

According to slave census data, five Councill family members, including Jordan Councill Sr.’s sons, enslaved people during the antebellum period, when 90% of settlers in the region did not enslave people, Plaag said.

Jordan Councill Jr., called “the father of Boone” in Arthur’s book, enslaved 13 people in 1850 and 11 in 1860, the most in Watauga County at the time.

The earliest burials in the white section were likely Councill family members, while the earliest burials in the Black section were likely those the Councills enslaved, according to Junaluska tradition and oral history documented in Susan Keefe’s book titled “Junaluska: Oral Histories of a Black Appalachian Community.”

Fences were erected around only the white section of the cemetery multiple times, once in 1898 and again in 1958, according to archives from the Watauga Democrat.

“Not only was it a segregated burying ground, but there was a physical separation of the white and Black sections,” Plaag said during an interview in January.

By the 1950s, the cemetery was overcrowded, and town officials closed both sections to new burials, apart from an exception for relatives of those already buried in the white section.

Black residents started burying their dead in Clarissa Hill Cemetery, while white residents began burying their dead in Mount Lawn Cemetery, which was exclusive to the “white or caucasian race,” according to the 1959 Mount Lawn Memorial Park and Gardens articles of incorporation.

In the following decades, the Black section was poorly maintained and overgrown, with no signage indicating to visitors they were standing in a historic cemetery.

2014-Present

Town of Boone preservation efforts

In 2014, the HPC received a letter from Junaluska community members detailing vandalism and neglect of the Black section and asked the town to purchase and renovate the cemetery, which was still privately owned by trustees appointed by the Councill family.

“You’d see people playing Frisbee, walking their dogs and not picking up, spreading out a blanket and suntanning,” Plaag said. “People probably didn’t realize it was a cemetery.”

In 2015, the Town of Boone purchased both sections of the cemetery from Councill-appointed trustees and funded projects to provide for the cemetery’s long-term preservation, including the removal of the chain-link fence in 2016.

In March 2021 at the town council’s request, the HPC began drafting interpretive panels to educate visitors of the cemetery’s existence and history.

The commission approved drafts of four interpretive panels during its July 10 meeting after over a year of research. The drafts were then placed on the Aug. 9 town council meeting agenda for council members to consider approving the language for installation.

“That is when all holy hell broke loose,” Plaag said during his lecture on the Boone Cemetery Jan. 25 at the Watauga County Public Library.

Aug. 1, 2023

Sesquicentennial Monument

During the Aug. 1 HPC meeting, the commission considered approval for Brenda Councill’s Sesquicentennial Monument, a bronze sculpture of three pioneers honoring the 150th Anniversary of Boone and its earliest families, many of whose descendants funded the project. Brenda Councill, an artist specializing in large-scale public pieces, painted murals for App State in the Belk Library and the Reich College of Education.

For public art to be installed on town property in downtown Boone, the town council and HPC must approve the project after a review of its historical legitimacy.

The monument’s proposed location was on King Street between Melanie’s Food Fantasy and the Boone Post Office, which Plaag said could interfere with town zoning regulations and plans for other monuments.

Among other historical inaccuracies found by the commission, the proposed text for the plaques claimed the Councill family store was located at the current Boone Post Office, which Plaag said is false, referencing Arthur’s book.

The commission then voted not to approve the monument due to concerns with the proposed location and historical inaccuracies.

Mary Moretz, a retired App State professor and sponsor of the monument, sent a letter to the town council in disapproval of the commission’s decision. Moretz said the decision “reeks of prejudice and discrimination” toward those of mountain descent.

Brenda Councill said her monument will still be installed on “private property in a prominent place on King Street,” but declined to comment on the specific location, which she will reveal soon.

Panels Controversy

The cemetery panels project was also discussed during the Aug. 1 HPC meeting, with the initial drafts placed in the meeting agenda packet.

Brenda Councill, a white descendant of Jordan Councill Jr., was looking through the packet after the meeting and read the initial drafts, which she said were “horrid,” and over the next week, contacted historians and families.

“They were in an uproar,” Brenda Councill said during an interview in February. “The drafts were filled with historical inaccuracies and unproven facts,” which she attributed to Plaag.

“I have some theories that I’m not going to get into about why these panels were so contentious,” Plaag said during his lecture on the Boone Cemetery. “All I will say is at that same moment, there was a discussion about memorializing people in the community. My perception is that because effort did not go well for the people advocating for that, the Boone Cemetery panels became a place where a fight could take place.”

One of the historians Brenda Councill contacted was her friend Michael Hardy, the 2010 North Carolina Historian of the Year and author of over 20 books on Western North Carolina, the Confederacy and the Civil War. Hardy reviewed the original drafts of the panels.

On Aug. 8, Brenda Councill and Hardy sent emails to town staff and officials, calling for the postponement of the project and for the writing to be revised with their complaints and suggestions acknowledged.

In Brenda Councill’s email endorsed by nine other Councill descendants, she said the drafts did not provide an accurate and inclusive representation of the cemetery’s history.

“Branding the entire Councill family as ‘racists’ will not stand at this juncture given the contrary evidence we will forward,” Brenda Councill said in the email.

She also said the proposed writing omitted “benevolent and progressive” actions of Councill ancestors, referring to Councill family oral tradition suggesting Jordan Councill Jr. and the other Councill slave owners donated much of their land to those they enslaved during Reconstruction.

“There is no evidence of this,” Plaag said during his lecture on the Boone Cemetery. “There’s lots of evidence of those Black families actually purchasing land from the Councill family much later in the 1880s and 1890s.”

According to “Junaluska: Oral Histories of a Black Appalachian Community,” residents of Junaluska suggest Jordan Councill Jr. owned the land of present-day Junaluska and many early-Black residents were sharecroppers for the Councills and other landowners.

“Some Black residents who moved into the area were able to buy their parcel outright or were allowed to clear land and keep a portion,” the book stated. “In any event, most Junaluska residents became landowners and homeowners.”

In Hardy’s email to town staff on Aug. 8, he said the original drafts failed to acknowledge notable graves found in the white section. He also disagreed with the use of the term “systemic racism” to explain the past disparities between the white and Black sections.

“Trendy catch phrases like systemic racism should be avoided at all costs,” Hardy wrote in the email.

He noted such terms are often misconstrued representations of past events and that the cemetery deserves a more inclusive interpretation.

“Systemic racism is a theory,” Brenda Councill said during an interview in February. “It is not a fact. That is a modern term that is not often used, especially among scholarly historians.”

According to the 2022-24 AP Stylebook, systemic racism, or institutional racism, refers to institutional systems that uphold and contribute to racial inequality throughout society. The term institutional racism was first used in 1967 by Civil Rights activists Kwame Ture and Charles V. Hamilton in their book “Black Power: The Politics of Liberation,” which argues institutional racism permeates U.S. history.

Plaag, a historian and private historical consultant, is a member of five different historical organizations, including the American Historical Association and the Organization of American Historians.

“Each one of them has in their code of ethics some form of language that requires us, when interpreting Black history, to talk about the effects of systemic racism on the Black experience in America,” Plaag said during his lecture on the Boone Cemetery.

By using the term systemic racism, Plaag said the HPC wanted to explain the cemetery’s disparity between marked graves in the white section versus the Black section, predicated by wealth inequalities between Black and white U.S. residents that have lasted since Emancipation.

“If you don’t have the money to pay for someone to carve a stone for you, you’re not going to put a carved stone on a dead loved one’s grave,” Plaag said.

Plaag agreed with Hardy’s suggestion for the panels to explain how cemetery segregation was common throughout the entire U.S. but said that only reinforces the influence of systemic racism on the Boone Cemetery.

“Given that both de jure and de facto segregation were rampant throughout the entire United States and for much of its history ignored or enabled by our local, state and federal governments; that sure seems to fit the definition of ‘systemic,’” Plaag said during the Aug. 9 town council meeting.

Plaag also addressed the statement made by Brenda Councill that the panels branded the Councill family as racists.

“I’m not aware of anything in the cemetery panel text or any other report of the HPC that asserts such a thing,” Plaag said.

From Aug. 8 to Nov. 3, town officials received at least 47 emails and other submissions of feedback on the project from Councill descendants and other community members.

The HPC made numerous revisions to the panels, including removal of the clause using the term “systemic racism.” Instead of four panels, the HPC decided to install two panels and one rules sign during their Oct. 17 meeting.

On Nov. 14, the HPC approved final drafts for installation. Plaag said he predicts the town will install the panels in the summer.

Brenda Councill said the revisions “partly” satisfied her group’s demands.

“We got some of the most offensive language removed,” Brenda Councill said. “Otherwise, there would have been legal ramifications.”

Plaag emphasized that Councill family members were not the only ones who submitted feedback, and the final drafts implemented many public suggestions.

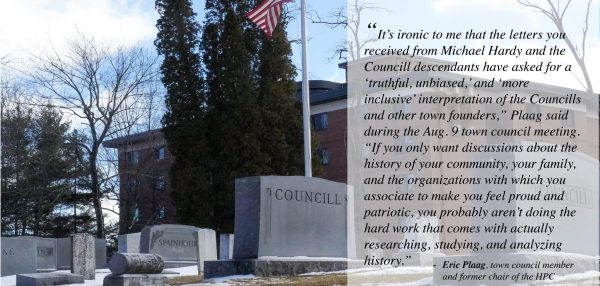

“It’s ironic to me that the letters you received from Michael Hardy and the Councill descendants have asked for a ‘truthful, unbiased,’ and ‘more inclusive’ interpretation of the Councills and other town founders,” Plaag said during the Aug. 9 town council meeting. “If you only want discussions about the history of your community, your family, and the organizations with which you associate to make you feel proud and patriotic, you probably aren’t doing the hard work that comes with actually researching, studying, and analyzing history.”

Matthew Deibler • Mar 24, 2024 at 11:44 pm

Very well written and researched article! Thank you for bringing this to light; I agree wholeheartedly with Plaag’s final statement.

Heather Williams • Mar 20, 2024 at 2:20 pm

Great Article! I particularly appreciate the point of view from Plaag about analyzing history. It’s difficult to discover sad and unjust episodes when we study our ancestors, but it’s important work.