Historic Black cemetery given long-absent recognition

Paige Hukill, left, Eleora Dunham, middle and Briar Ward, right, dig up soil to make space for the gravel and stone to be laid underneath, Oct. 28, 2022.

November 1, 2022

A group of students, faculty and community members arrived at a grassy hill in the heart of Boone Oct. 28 to install something long-absent: gravestones.

“This grassy hill is where at least 165 Black community members of Boone have been buried since the 19th century,” said Alice Wright, a professor of anthropology at App State. “Their graves are not only unmarked, but until much more recently than you would strictly be comfortable with, this side of the cemetery was actually physically divided.”

The hill referred to by Wright is the site of the Town of Boone’s historic Black cemetery. Until the mid-20th century, many of the residents of Junaluska, Boone’s African American community, were laid to rest here.

In 2017, a monument was installed with the names of everyone known to be buried in the cemetery. However, until Friday, the individual graves did not have permanent markers. Some of the graves likely had marker stones when they were originally established, but these were probably removed or disappeared over time, Wright said.

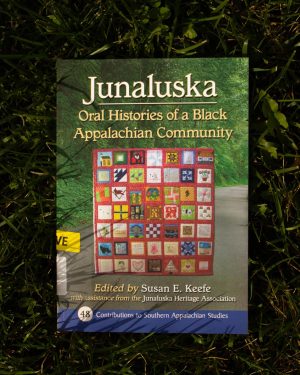

The group of volunteers, organized and led by the Junaluska Heritage Association and Wright, worked through much of the morning on this project. Prior to its start, words were shared by Wright, Junaluska Heritage Association facilitator Roberta Jackson, and retired anthropology professor and longtime collaborator with the Junaluska community Susan Keefe. Following this, those present were divided into work groups and began installing the marker stones.

Each flat marker stone was installed after the existing temporary marker and a layer of sod were removed. Following this, gravel was laid in the resulting holes before the stones were placed to prevent the markers from sinking or becoming overgrown.

These stones are unmarked, as the identities of those known to be buried in the cemetery have not been connected to individual graves.

“We don’t know who’s in what grave,” Jackson said. “So what we did was research the people who were buried there and the ones that didn’t have tombstones, then we had a monument done. But then we realized there was a lot of other people that we didn’t know that were buried there.”

Several of those present, including Kristen Baldwin Deathridge, a history professor at the university who has worked with the Junaluska Heritage Association for much of the past decade, commented on the importance of the project in recognizing the history and legacy of Junaluska’s past residents.

“It’s particularly important, I think, to honor the stories of people when we talk about the founders of Boone, you know,” Deathridge said. “It is important to also talk about the people who were enslaved and the free people of color who lived here and contributed to the town, and their stories are just as important, if not more important, because they haven’t been told.”

Senior anthropology student, Britan Sides, shared a similar sentiment.

“It’s really important because there’s so much Black history that is not told in history classes that many people don’t know about because it’s been ignored throughout history,” Sides said. “Through this, we are recognizing that these graves and these people are here, and they deserve to be recognized and they deserve to be honored.”

In addition to its recognition of the history and legacy of Junaluska’s residents, Keefe talked about the increased visibility this project will bring to the cemetery itself.

“I’m so grateful for all the students showing up because when you look at the marker, it’s not readily apparent that there were graves actually over this entire area, you know, but so this work will actually demonstrate that, and that’s, I think, that’s really, really important,” Keefe said.

Throughout the project, emphasis was placed on ensuring the work being done aligned with the wishes of the Junaluska community.

“I just want to be sure that what we’re doing is what members of the community want and that it is honoring them, and it’s my understanding from the conversations that I’ve had that it is, that this is something people have wanted for a long time,” Deathridge said. “And so it’s really great to be able to do it.”

Jackson said despite many members of the Junaluska community being unable to participate in projects like this due to age, the work has been well-received.

“We don’t have a lot of people who participate in things because our community is old,” Jackson said. “But they are pleased with it and we try to keep the community informed, usually through announcements at our church.”

Reflecting on an experience she had during the original marker’s dedication, Jackson additionally explained the value of these projects in the cemetery. She recalled meeting a man from out of town who pointed out the name of one of his relatives on the marker. Until then, he hadn’t known where she was buried.

“So it’s just to educate people too and to give them a little bit of their own history,” Jackson said.

Expressing similar thoughts, Wright discussed the unique opportunities for reflection that places like Boone’s historic Black cemetery can have.

“Their descendants are still here and the histories that they lived are still reverberating in all of our experiences today,” Wright said. “Even if the past is dead and buried, any opportunity we have to grapple with that past, think about it critically and respectfully and empathetically as fellow human beings, I think stands to have a positive impact on our present and on our future.”

Chris c • Nov 1, 2022 at 7:52 pm

This is an amazing article. William Becker is clearly a talented young man and I look forward to reading his work and expect great things from him in the future.