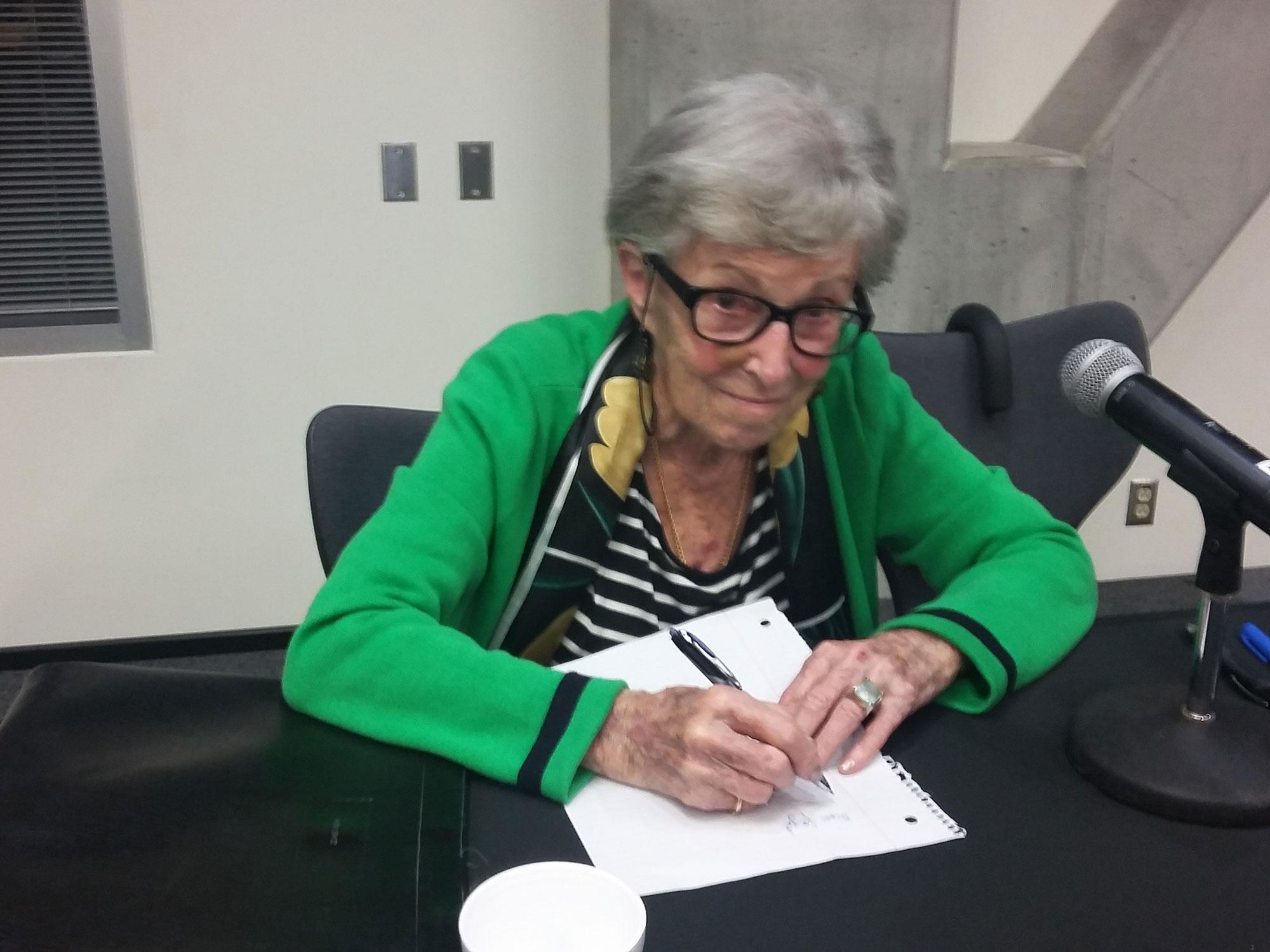

Auschwitz survivor Susan Cernyak-Spatz spoke to a packed room about her experiences during the Holocaust and the importance of learning the lessons of those events Thursday in the Parkway Ballroom in the Plemmons Student Union.

Cernyak-Spatz was living in Berlin with her family in 1933, the year Hitler came to power. Shortly after, the family left for Vienna, where a branch of her family’s business was located.

In 1938, the Nazis took control of Austria and the family fled once again.

“We left Vienna overnight, practically, leaving behind a six-room apartment, with the silver and china and glass in the cupboards in the dining room, with the clothes in the closet, and the food in the refrigerator,” Cernyak-Spatz said. “And with a little suitcase in hand, I did my first flight from Vienna to Prague.”

In 1939, it became apparent that the family would have to leave again. Her father left before the rest of the family on Aug. 31, a day before Germany invaded Poland.

Cernyak-Spatz’s father was able to escape to Belgium from Poland. Cernyak-Spatz and her mother were left in then-Czechoslovakia.

They were first transported to Theresienstadt in May 1942.

From there, Cernyak-Spatz was sent to Auschwitz-Birkenau in January 1943.

“The first thing that hit you was a smell. I can’t even say smell, it was a stink,” Cernyak-Spatz said. “And what you saw in front of you as the train moved in was the chimney, that was flames shooting out and black smoke curling out of it.”

The Jews brought in by bus were divided into groups, one headed for the gas chambers and the other for the labor camp.

Cernyak-Spatz and other members in her group were taken into a sauna where they were stripped, shaved and subjected to cold showers.

After this, the inmates were issued clothing, including the uniforms of dead Soviet soldiers.

Cernyak-Spatz was “lucky enough” to get shoes, which allowed her to avoid infections that would have meant certain death.

Then, inmates were given the “absolute abyss of dehumanization”: A small feeding bowl.

“It was your entire civil utensil,” Cernyak-Spatz said. “You had no spoon, you had no knife, you had no fork, you had no handkerchief, you had nothing. You were at the level of an animal.”

During her time at the camp, Cernyak-Spatz learned several lessons for survival.

One such lesson came early on, when camp personnel officer ordered Cernyak-Spatz and those with her to climb to the top bunks.

Cernyak-Spatz later learned there was a practical reason for this. The inmates were not allowed to use the latrine at night and if one of the few buckets left at the end of the bunks was too full, inmates were forced to use their feeding bowls.

The contents were then emptied through a slit of the bunk, down on the other bunks.

Thanks to the help of a friend, Cernyak-Spatz was able to secure various jobs “on the inside,” a development which allowed her to survive.

Auschwitz-Birkenau was evacuated in January 1945, forcing 58,000 people out of the camp.

Cernyak-Spatz and others in her group were sent marching through the forest to a train station.

Cernyak-Spatz was transported Ravensbruck, a women’s concentration camp, where she stayed until April.

In April, the Nazis and allies had a prison exchange in which the allies requested the women from Ravenbruck. Red Cross buses were dispatched to pick up the women, taking them in groups based on nationality.

Cernyak-Spatz decided to stay with her group, walking west on foot. At one point, the group was forced to avoid crossfire from an exchange between unidentified groups of soldiers.

The group eventually made it to an American checkpoint. Cernyak-Spatz asked an American soldier, “Where are we supposed to go?”

“You’re speaking English. Why?” the American soldier responded.

“Because I learned it,” Cernyak-Spatz said.

“Well, go back where you learned it from,” the soldier replied. Another prisoner who was with the soldier said that they could not go back, that they had come from an extermination camp.

“I shall never forget the look that that G.I. gave me,” Cernyak-Spatz said. “He said, ‘What the hell is an extermination camp?’”

She continued with the story:

“And I had to think, there was this young man probably in his early 20s who had served three years, who was planning to liberate the occupied people of Europe, the oppressed people of Europe, and he had no idea who the most oppressed people were,” Cernyak-Spatz said.

The soldier redirected Cernyak-Spatz and her group to a village where they could meet with his commanding officer.

“All of a sudden, I realized I could stand, I could sit, I could walk backward, I could do what I wanted. I was free,” Cernyak-Spatz said.

Aftermath and Lessons

After the war, Cernyak-Spatz came to the United States, got married and had children. She is a German literature Professor Emerita at UNC Charlotte.

During her account, Cernyak-Spatz did not discuss the fate of her mother. In response to an audience question, she called it a “personal matter,” but mentioned that her mother had decided “to leave with her friend.”

In her first time in the United States, she said that few Americans wanted to hear about the Holocaust. Only during the 1961 trials of SS officer Adolf Eichmann did this seem to change, Cernyak-Spatz said.

At several points during the presentation, Cernyak-Spatz criticized the behavior of the free world, particularly in the early years of the Nazi regime.

“I have often wondered, was either the free world so stupid or so indifferent? And since I couldn’t think that the whole world was so stupid, I could only deduce that they plain didn’t give a damn,” she said.

Cernyak-Spatz finished her presentation with the lesson she wants all to learn from the Holocaust.

“If any of you might have a profession which might involve hurting or killing one human being, think of what I’ve told you,” she said. “Don’t let anybody, be it a multinational corporation or a government with the best salaries in the world, don’t anybody let it corrupt you and use your humanity.”

Story by: Kevin Griffin, Staff Writer