OPINION: Misbranded and misconceived, living with ADHD is different than the public perceives

April 10, 2019

From 2016-17, 10.6% of children between the ages 5-17 were diagnosed with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. ADHD is a neurodevelopmental disorder diagnosed in children that may last into adulthood and is commonly characterized by trouble paying attention, poor impulse control and an excess of energy.

I have ADHD, and while all of those are true, reducing it to those characteristics diminishes the experiences of people with the disorder.

Most people’s understanding of ADHD is lacking and hold a lot of misconceptions. I know I was ignorant before I was diagnosed and began researching my condition.

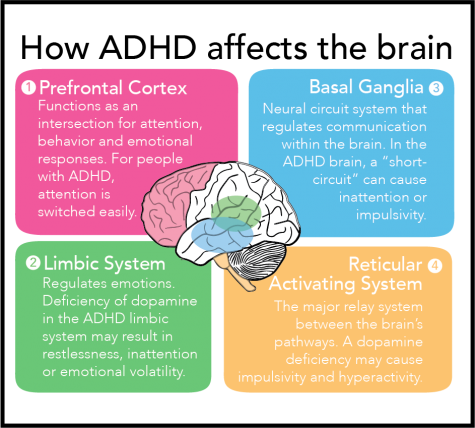

One of the biggest misconceptions is that ADHD is a mental illness, instead of a developmental disorder. The brain of someone with ADHD is biologically different than someone without.

An ADHD brain produces less norepinephrine, a neurotransmitter directly linked to dopamine, which helps control the reward and pleasure center of the brain.

In February 2017, researchers at Radboud University found that five areas of the brain, the caudate nucleus, putamen, nucleus accumbens, amygdala and hippocampus, were smaller in the brains of people with ADHD. The researchers found this by examining the brain volumes of 1,713 people with ADHD and 1,529 without ADHD using a MRI scanner.

Another misconception of ADHD is that everyone with the disorder experiences the same symptoms and that lesser versions are called ADD, or attention deficit disorder. ADD does not exist, and three kinds of ADHD exist: inattentive, hyperactivity-impulsive and combined.

Inattentive type, formerly known as ADD, is more common in girls and adults. It’s characterized by forgetfulness, a lack of attention to detail and inattention. Hyperactive-impulsive type is more common in children and men; it’s characterized by an excess of energy and a lack of self-control. Combined type, which is what I have, is a mix of both. These types of ADHD function less as concrete divisions and more as labels applied to the spectrum of the developing ADHD brain.

A little-known aspect of ADHD that affects the lives of many is executive dysfunction, which I struggle with the most. Executive functioning is the cognitive and mental ability to enact goal-oriented action. People without ADHD can transition seamlessly between wanting to do something and doing it. For me, there’s a wide divide between the two. For example, I may want to do something as simple as eating, but can’t do it for hours without an outside influence interrupting my trance like a friend inviting me out or a telemarketer calling me. Although I want to, I can’t. My brain literally cannot execute the task.

Another lesser-known aspect of ADHD is hyperfocus. Hyperfocus is sustained, intense concentration on a single interest or subject for a period of time. This might seem out of place because a major symptom of ADHD is the inability to focus, but it has to do with the reduced levels of dopamine in the brain. Because ADHD brains produce less dopamine, it’s harder for people with the disorder to “shift gears” and move their focus to more boring tasks. Generally, people with ADHD will hyperfocus on media, creative projects and activities they find pleasurable.

It isn’t all bad for people diagnosed. People with ADHD are, on average, more creative than people without ADHD, according to a 2006 study published in the journal “Child Neuropsychology.”

Like most people with ADHD, my experience has been a mixed bag. I wasn’t formally diagnosed until December 2017. Growing up, my teachers would tell me I was smart, but I didn’t apply myself. I did all right in primary school, but that’s as much a result of my intelligence as my parents’ attentiveness and making sure I didn’t fail. After I was diagnosed and started medication, I could concentrate and apply myself. My grades went up drastically because I could study and do my work on time. I still struggle, but my quality of life has improved.

I can’t imagine a life without ADHD. I can’t imagine a life where my imagination isn’t filled with countless words that I can’t describe because of the disconnect ADHD has created. It’s bittersweet because without ADHD, I could describe them, but I also wouldn’t have them.

ADHD is complicated, and this is by no means a comprehensive explanation of the disorder, but hopefully it’s enough for people to gain a basic understanding so they can better relate to and understand people with ADHD.

Shivangi • Jun 25, 2023 at 4:19 pm

No words to thank this depth insight, I am able to manage it much better after reading this. May God bless you for such an unconditional gesture of kindness. Lots of love and blessings ❤️

Maricel • May 28, 2023 at 3:20 pm

Thank you for this article. It is very important and helpful to learn about ADHD. Many years ago I had students that were diagnosed with ADHD. This article will help me a lot.

Laurelle • Jul 12, 2022 at 8:26 am

Thank you for this article! Textbooks definitions are not always easy to understand but life experiences, we can easily relate to. I will share this with all the people in our circle to better support a child diagnosed with ADHD.

Tomeeka Veljanov • Jun 2, 2021 at 7:53 pm

I have ADHD and Autism I have been diagnosed 2 years ago and now I am getting better about accping the diagnosis and taking medication to help me to calm down

Katie • Mar 16, 2021 at 7:58 am

Thank you for this article, it was very helpful as I’m writing an essay on ADHD. I’ve long suspected I

have some of the symptoms and your explanation and personal experience is interesting and explains the symptoms in a relatable way 🙂

S • Aug 11, 2019 at 1:17 pm

I am a 49 year old woman and was diagnosed a few days ago. I am likely inattentive. My life suddenly makes sense and I wonder what would be different about it had I been diagnosed sooner. Thanks for the post!

David Medberry • Apr 11, 2019 at 1:39 pm

Q,

Thanks for this deeply personal but deeply relevant dive into ADHD. It is likely very under diagnosed (especially for those of us in your parents’ generation.)

I will reference your post as I talk to others about this topic.

-d