Every semester, college students excitedly peruse their course list and program of study to create a perfect class schedule. One often-used tool is Rate My Professors, a website where students give anonymous reviews of their professors, including their grade, rating of the class and additional comments. While this website may seem informative on its face, it is plagued by several statistical issues that put into question the accuracy of these ratings.

Most departments will offer classes with a choice of two or three professors who could have drastically different teaching styles. However, there is no real way for students to gauge the best fit until syllabus week when it is often too late to switch sections.

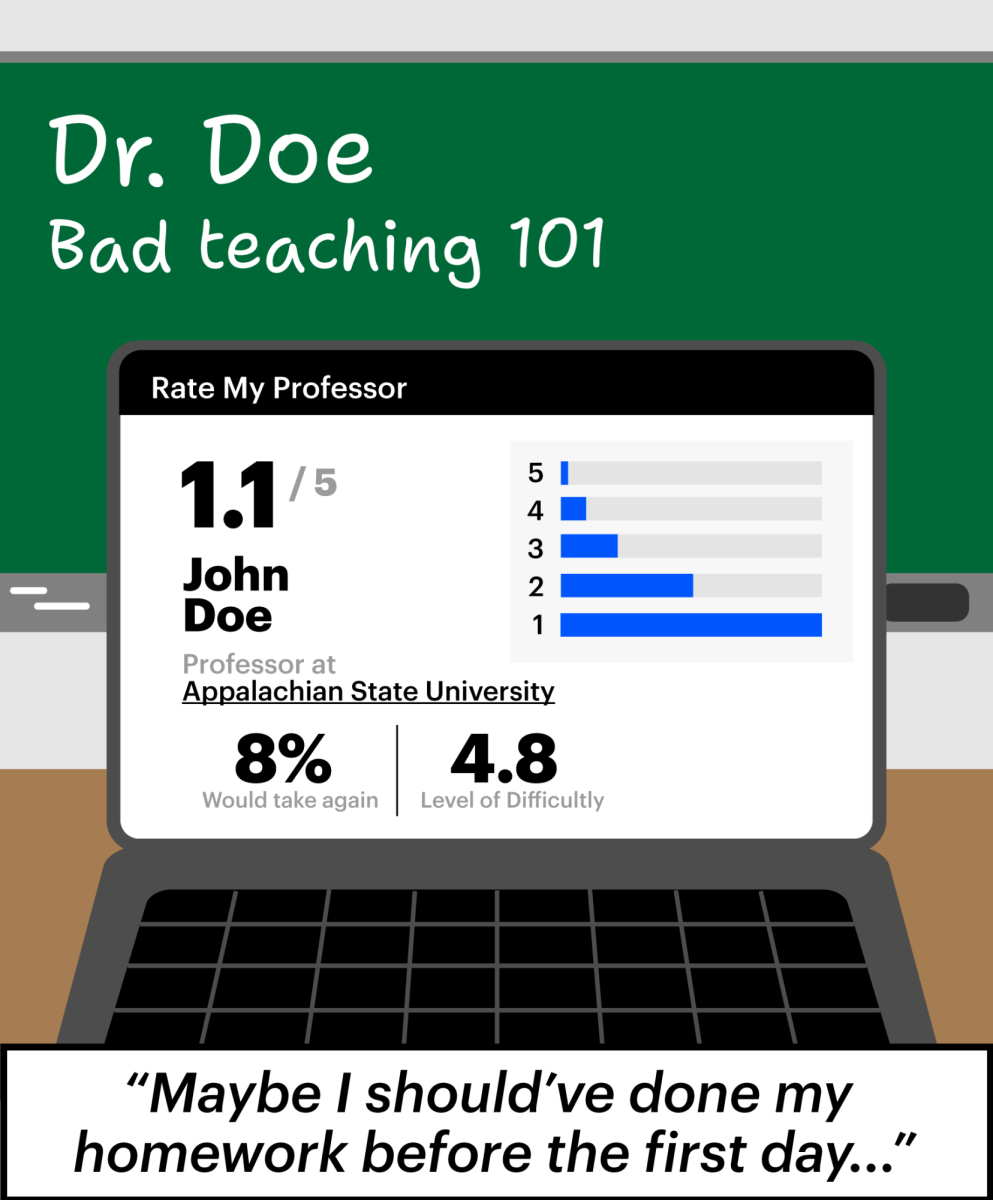

This is where Rate My Professors comes in. Since it is integrated with the widely used scheduling app, Coursicle, students are able to see an aggregate score of each professor as they scroll through class options. While it’s enticing to make conclusions about professors based solely on these online ratings, two statistical problems should make students think twice.

The first is small sample sizes. Oftentimes professors, especially newer ones, will have few ratings. This is an issue because a small sample size does not accurately capture the true range of potential outcomes. It’s like flipping a coin three times and concluding landing on heads is impossible because it came up all tails.

Similarly, having just a few reviews out of the hundreds or thousands of people a professor has taught is not enough to create a sample that represents the opinions of all past students. This idea is shown in the law of large numbers, a statistical theorem which states that as the sample size increases, the sample mean approaches the population mean.

Put simply, a large enough sample size is needed for the average score listed on Rate My Professors to approach the actual average opinion of all students who have had that professor. A sample size of dozens of reviews may be large enough, but less than ten is definitely too small. However, even if the sample size is adequate, the sample must be randomly chosen to draw accurate conclusions.

Statistical bias describes ways in which samples are not randomly chosen. In the case of Rate My Professors, voluntary response bias is the main one at play. This bias involves a sample taken only from people who choose to respond, selecting those with stronger opinions. Those who adore or despise their professors will feel more compelled to leave a review, causing those extreme ratings to be overrepresented.

Meanwhile, students who don’t feel strongly either way tend to have less motivation to comment, so their experiences become underrepresented. This makes for a collection of especially positive or negative reviews, skewing the perception to the extremes.

That being said, there are still meaningful insights that can be drawn from the website. Students should look through the open-ended comments and tags section to see concrete facts about the professor’s teaching style, such as their attendance policy or textbook requirement. Distinguishing those comments from the opinions of scorned former students is key to making educated class choices.

In the information age, it’s easy to become comforted with knowledge, and anxious without it. The impulse to tell the future is strong, and to control it, even stronger. However, the security blanket of other’s past experiences is more a thinly veiled solace than an accurate prediction model. Growing as a college student means coming to terms with not knowing your future, or your professors.

Navya • Sep 24, 2024 at 4:47 pm

While I agree with much of the article, Rate My Professor is still better than going in blind.

Emma • Sep 23, 2024 at 11:01 pm

very interesting..

Paige Wilkinson • Sep 23, 2024 at 10:58 pm

Great article! I totally agree with your take on Rate My Professor!