One night in the middle of July on the twisty and rugged road of NC Highway 181, two Appalachian State astronomers believe to have caught on camera one of North Carolina’s unexplained mysteries, the Brown Mountain Lights.

There are many myths and stories surrounding the lights and their origins. The common ground these stories share is the description of the lights as orbs that appear then disappear while staying stationary in the same spot in the sky.

Daniel Caton, a physics and astronomy professor and the director of observatories at Appalachian State University, has been chasing the Brown Mountain Lights since late 1985. Caton and R. Lee Hawkins, Appalachian State’s observatory engineer, set up two cameras at one site to attempt to document the lights.

Camera one looks at Brown Mountain from the Gingercake area and generally runs dusk to dawn while sometimes starting late, and camera two looks up Linville Gorge from the south only runs midnight to 5 a.m. due to the expenses of the satellite internet connection, according to Caton’s research website that is attached to his Appalachian State website, BrownMountainLights.org.

Camera one looks at Brown Mountain from the Gingercake area and generally runs dusk to dawn while sometimes starting late, and camera two looks up Linville Gorge from the south only runs midnight to 5 a.m. due to the expenses of the satellite internet connection, according to Caton’s research website that is attached to his Appalachian State website, BrownMountainLights.org.

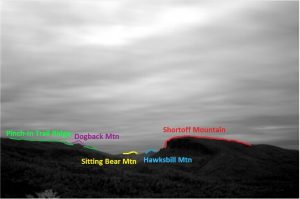

Caton said the lights have been mainly reported in three different locations surrounding the Linville Gorge area: Wiseman’s View off the Pisgah National Forest access road, the Brown Mountain Lights overlook marker on NC Highway 181 and at the Lost Cove overlook at mile marker 310 on the Blue Ridge Parkway.

Caton became interested in researching the lights and had a file on them ever since he moved to Boone. He said in the mid-late 1980s he had an intro astronomy student claim he had seen the lights and filmed them. The claim interested Caton and he started going out to Wiseman’s View, about an hour drive down the mountain, to take a look at the lay of the land. Although his former student never gave him the video, Caton joined forces with Hawkins in 1999 to try and document the lights.

Caton recalled upon a time where they thought they caught the lights on the camera at looking down at Linville Gorge. Caton describes it as a “brief pulse of light” and a “fan of faint light” that had a flashbulb duration. Caton describes this encounter as a “Did-you-see-that?” moment. Others claim to see sphere shaped orbs of light dance across the mountain’s skyline and even as close as 20 feet away.

“Lee and I saw a glimmer of light one night when we were out there,” Caton said.

It was impossible to tell what it was, Hawkins said, finishing Caton’s sentence.

It was not the firework type displays that people often describe, it could have easily been a flashlight in the woods, Hawkins said.

On an unrelated night, while coming back from the Asheville area, Caton decided to stop by the site. As he was staring out he looked up and saw a very bright light, brighter than any star.

“Even brighter than Venus. It did not move, it just stayed there for several seconds and dissipated,” Caton said. “That is about as close I gotten to seeing the lights.”

A video of the lights captured on July 16-17 from 9:40 p.m. to 5:37 a.m. showed something that does not look like anything they have seen before, Caton said. The stationary light appeared in the same area with no lateral movement between exposures, four times in a span of 20 minutes. Caton said people got excited about that, “but we wanna see more before we get too excited.”

Viewers can look at footage from the camera feeds in real time on Caton’s website. He explained that the videos are built every day from both cameras by stitched together 30 second long exposures, one after the other all night. He said they are made up of about one thousand clips. Caton also said in a 30 second exposure almost anything moves, airplanes and even stars trail with the Earth’s rotation.

July’s video “just did not show any streaking, unless it moved, reappeared or was coming dead straight at us,” Caton said. Which is unlikely because if an airplane were doing that it would peel off one way or the other unless “it is not only approaching us but diving into us, so to maintain line of sight, it would move up, and [the video] did not show that.”

Hawkins agreed and said they had two cameras at that site to reject false positives and this appeared on both cameras at the same locations. To put this in perspective, they have a couple million images and so far have only seen unusual things on four of those images.

All this to say it certainly doesn’t happen at the rate people think it does, Caton said.

Hawkins and Caton have been out to Wiseman’s View and the NC Highway 181 overlook together and separately a total of 30 or 40 times. Hawkins said they mostly find that 99.9 percent of the people who go there expecting to see the lights and to them any light they see is a Brown Mountain Light. He said that they take a telescope or binoculars with them to examine the lights and by using those instruments, they find that the sources of lights come from campfires, people with lanterns walking around the gorge or car headlights and tail lights.

“Especially ATVs on Brown Mountain and even such crazy things as out of focus dust when taking a photo at night,” Hawkins said. “That is a popular ghost theory; when you take a flash photo at night the out of focus blobs look like ghosts but they are not ghosts. It is just dust in the air that your camera can’t focus on.”

Other things Caton and Hawkins have noticed is that the people who claim to see the lights do not have any conception of scale.

“They haven’t been outdoorsy types, they don’t understand where people can and do walk in the woods,” Caton said. “They think there is no way people can be walking in that rugged area.”

Caton also suggests that another reason why people report false sightings is because they spend most of the time inside at night and they do not know the nightscape.

Caton said they began to get cynical in 2006, and started to think all the reports were bogus. But after Caton did an interview with an Associated Press reporter from the Triad area, “Then I started getting emails from people detailing close up encounters,” he said. “One who had seen it in the parking lot. It is one thing to be confused about something that is a thousand feet away and then it’s another thing to see this thing 20 feet away.”

That is when Caton and Hawkins started to think that the descriptions of the encounters started to sound like ball lightning, which is something they do not yet understand and Caton said that is how they got back in the game.

Peter Soulé, professor of geography and planning, wrote in an email that ball lightning is thought to be a magnetically held together concentration of corona discharge, similar to St. Elmo’s Fire. St. Elmo’s Fire is a concentration of sparks that has often been seen on a ship’s mast, power poles or pointy objects like flag poles. With electrical discharge, like a bolt of lightning, there is charge separation. “For ball lightning, the positive, sparking charges are thought to be held together magnetically,” Soulé wrote. “I’ve never seen it, but have had a number of my students describe it to me as a ball of sparks that moves and floats about, likely by micro wind currents.”

Unlike other groups, Hawkins said they think that if the Brown Mountain Lights does exist, there is a physical explanation for it.

“We are not looking at this from the mythical or ghostly point of view that has a metaphysical explanation but no physics explanation,” Hawkins said. “This is not the way we look at life and science.”

Leigh Ann Henion is a travel writer from western North Carolina that went on a trip to the camera site with Caton and Hawkins and a couple other scientist about three years ago.

“The notion of mysterious lights hovering over mountains got lodged in my mind as a child growing up in North Carolina,” Henion wrote in an email.

She didn’t know much about the Brown Mountain Lights when she started looking into the phenomenon for Our State Magazine in May 2014.

Henion then published her 2015 book, “Phenomenal: A Hesitant Adventurer’s Search for Wonder in the Natural World” about how she chased natural phenomena around the world to “reawaken my sense of wonder,” she wrote.

She went to the Serengeti to see wildebeest migrate, the Arctic for the northern lights and Venezuela for the everlasting lightning storm. Even though the Brown Mountain Lights are not in “Phenomenal,” she wrote that they are thematically connected.

“I was amazed to realize how much and yet, in the scheme of things, how little we know about our home planet,” Henion wrote. “It might seem like we live in a done-over world, but there’s plenty left to be explored. Earth is full of marvels and mysteries. We just have to pay attention.”

Henion wrote that the research Caton and Hawkins are doing with the lights are a reminder that science is a never ending process of discovery and not merely rote memorization.

Despite not knowing for sure how to explain the Brown Mountain Lights, Henion wrote they pull people out of their living rooms, into the natural world.

“You might not see floating, glowing orbs if you go out to Brown Mountain tonight,” Henion said. “You might see a shooting star, a moon halo, or some other extraordinary thing you’ve never thought to search out.”

Henion encourages seekers and cynics to make time to stare into the night sky, and suggest that by doing this, “you are opening yourself to the possibility of awe.”

Story by: Katie Murawski, A&E Editor