Colin Wishneski curated this story by Gordon Clay, which The Appalachian published on April 20 1982.

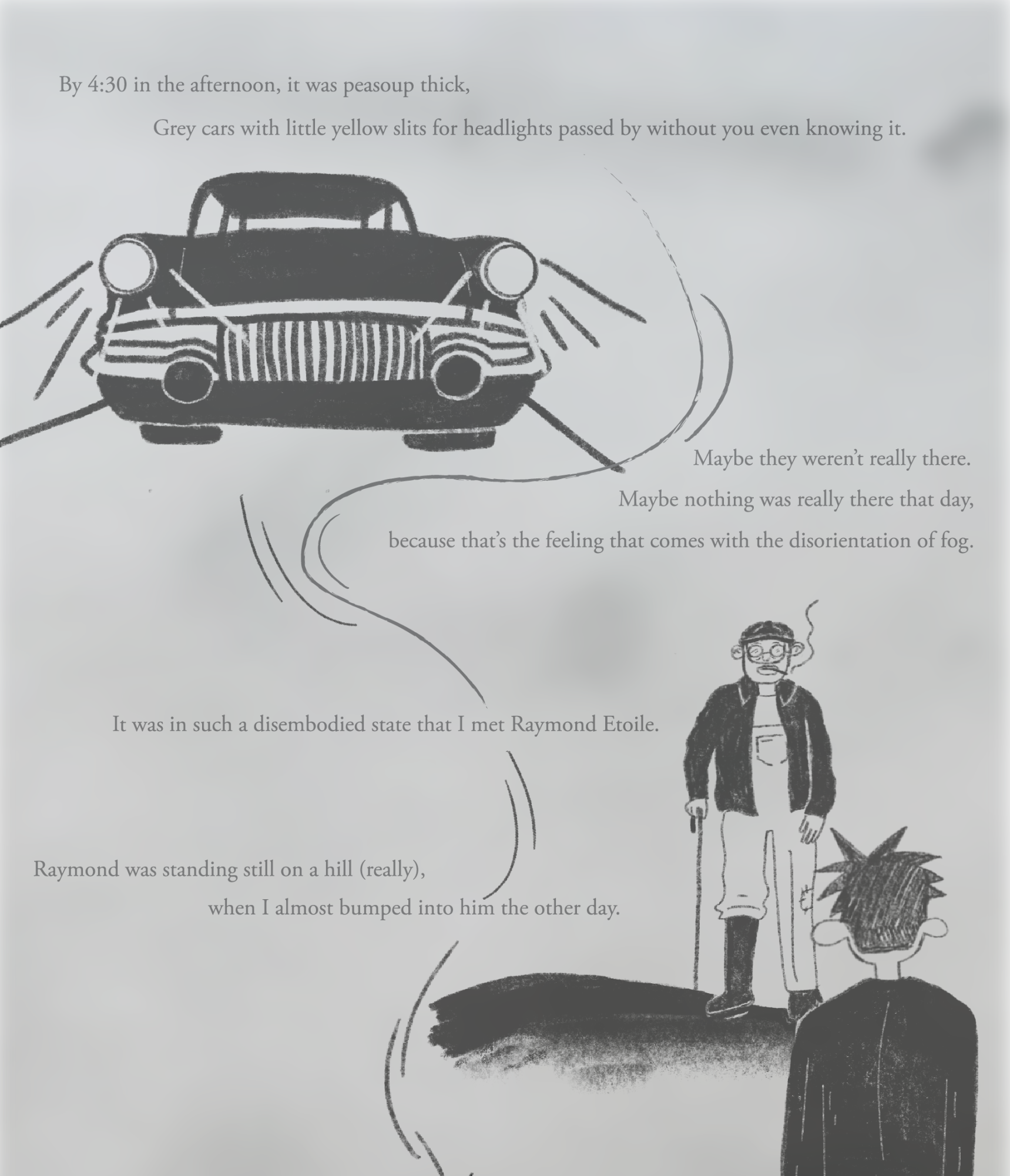

It was one of those days–not too far gone–when the weather couldn’t decide what it wanted to do. It was clear and cool in the morning, warm and wet in the afternoon, and towards twilight, while it pondered its next mood/move, it got foggy. By 4:30 in the afternoon, it was peasoup thick, Grey cars with little yellow slits for headlights passed by without you even knowing it. Maybe they weren’t really there. Maybe nothing was really there that day, because that’s the feeling that comes with the disorientation of fog. On those kind of days, you know what it’s like to be a goldfish in a bowl who swims in muddied waters. It was in such a disembodied state that I met Raymond Etoile.

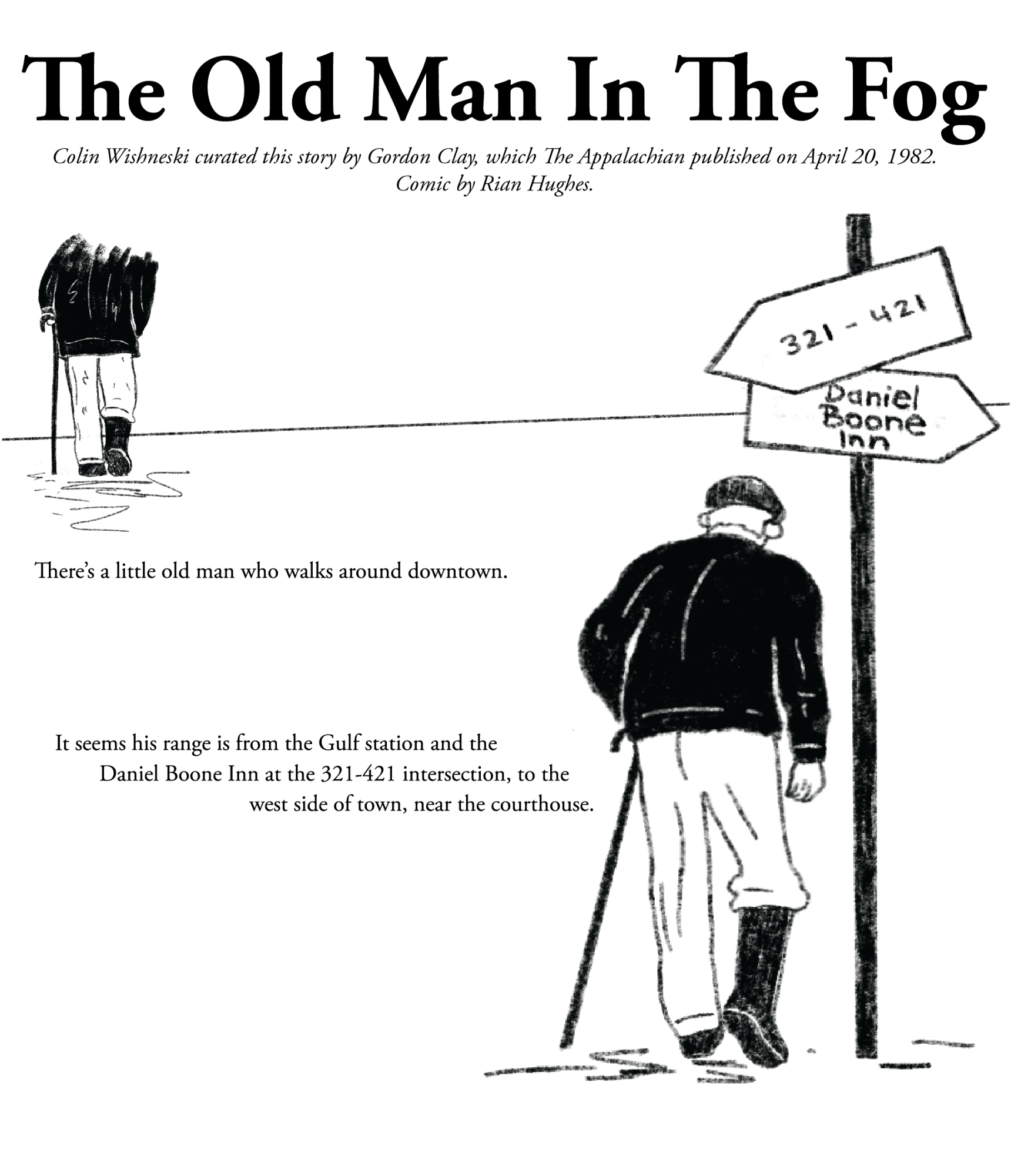

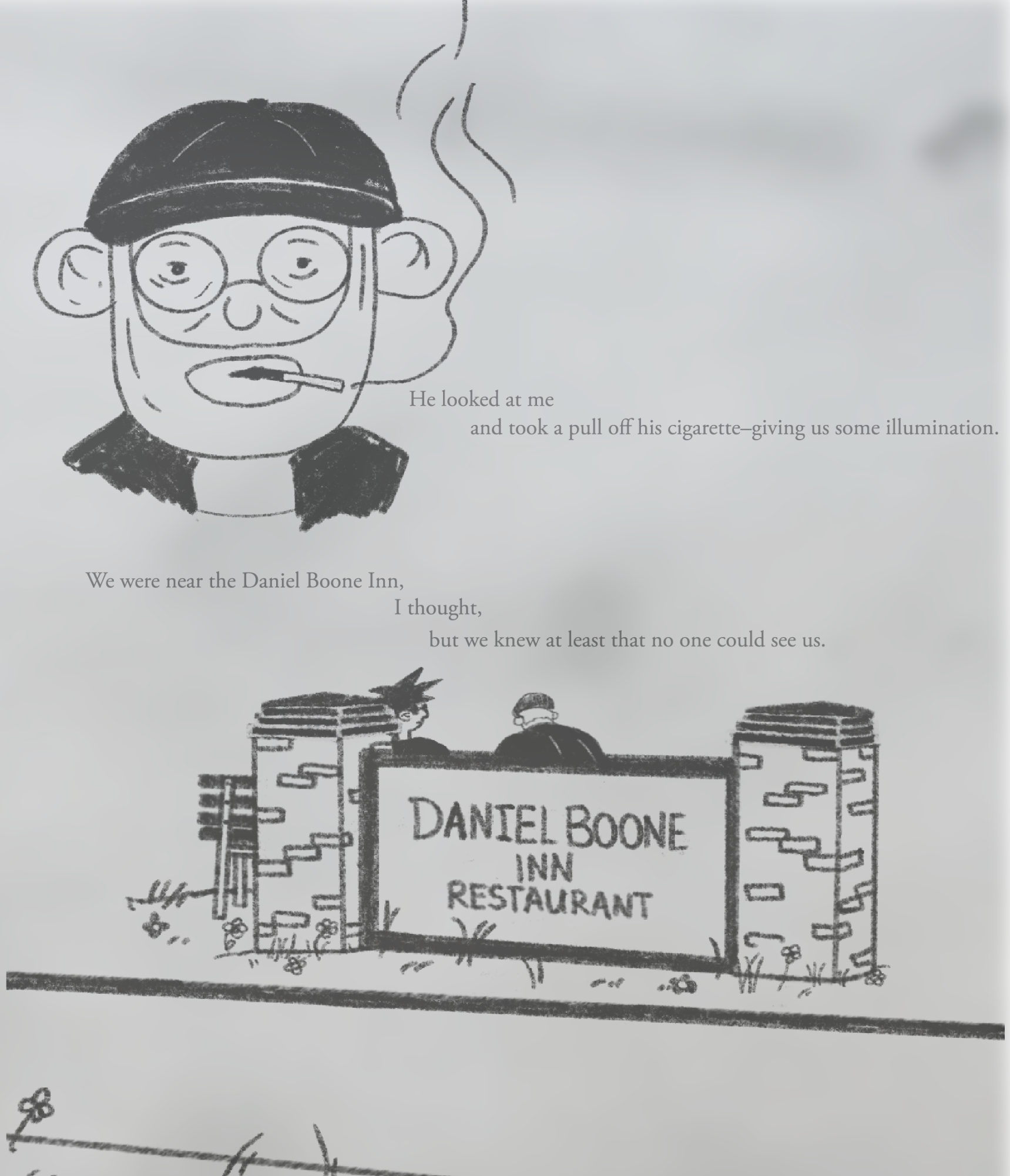

Raymond was standing still on a hill (really), when I almost bumped into him the other day. He looked at me and took a pull off his cigarette–giving us some illumination. I backed off to the culturally, comfortable distance that we place between ourselves and made a remark about the fog. We were near the Daniel Boone Inn, I thought, but we knew at least that no one could see us. Gears changing out on the highway interrupted an otherwise consistent silence. It was from this earth-intense atmosphere that his voice escaped.

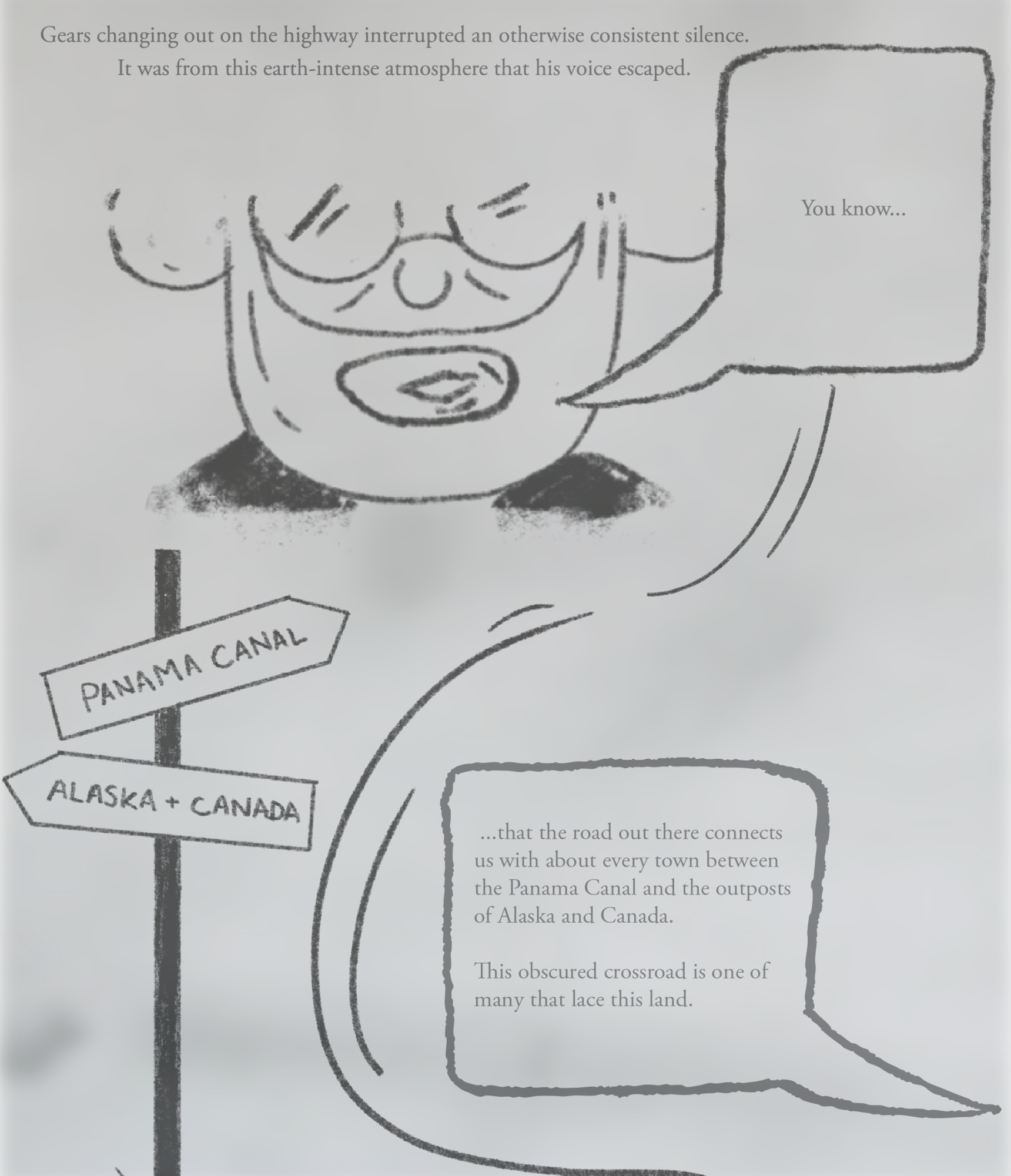

“You know,” Raymond started, “that the road out there connects us with about every town between the Panama Canal and the outposts of Alaska and Canada. This obscured crossroad is one of many that lace this land. And as long as there is a vehicle to hitch a ride from or a road to walk down, you and I will have a certain freedom.”

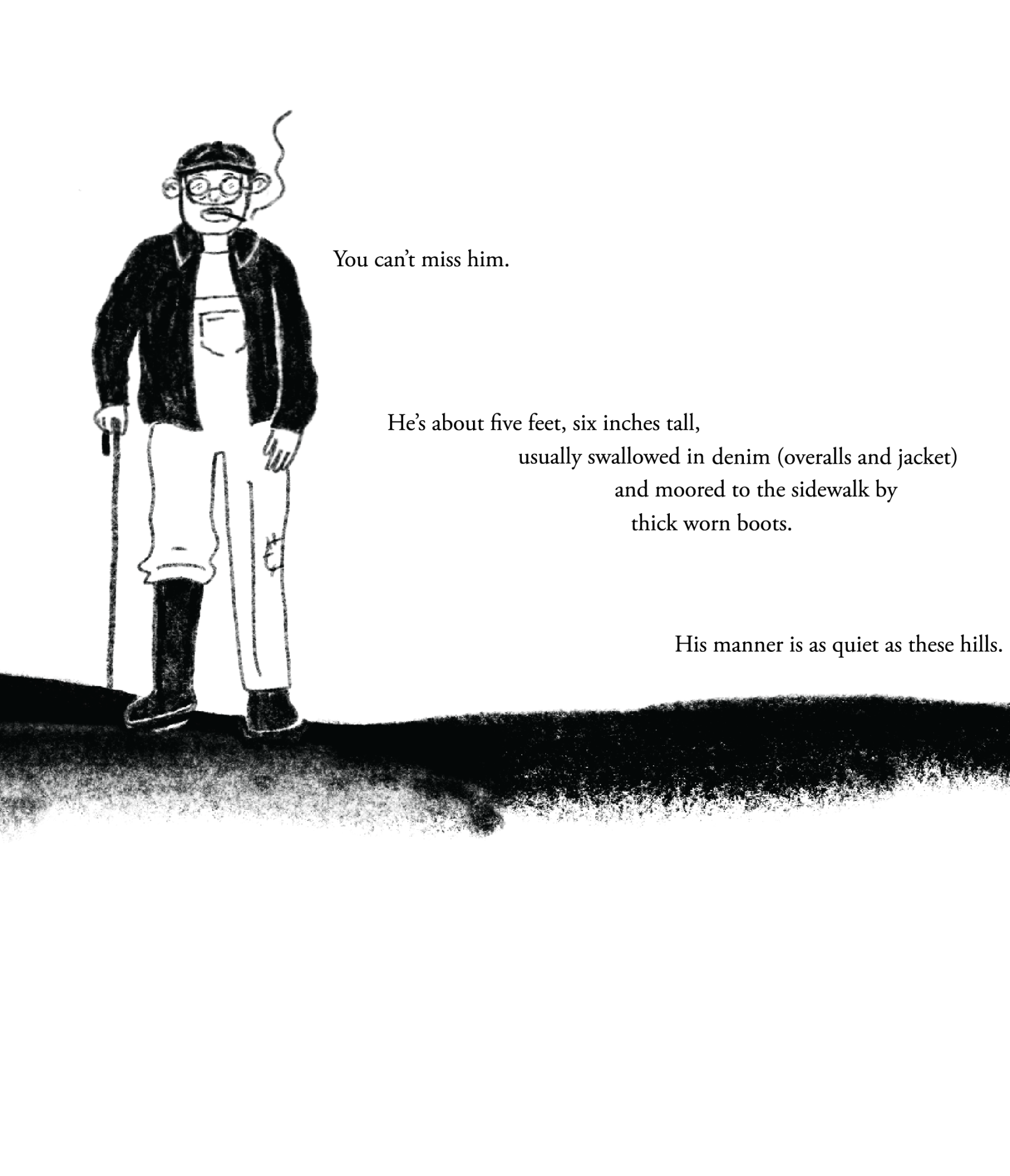

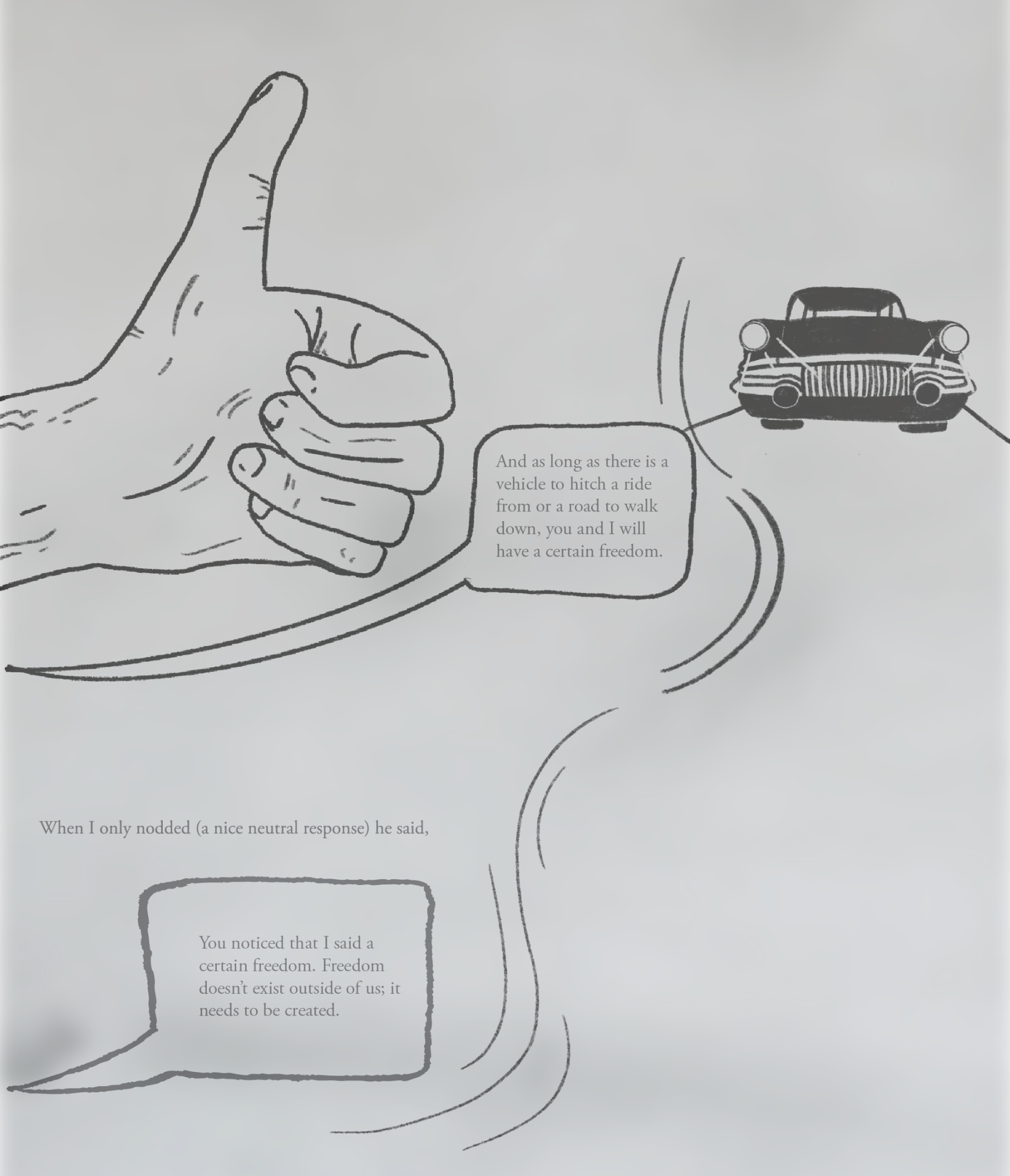

When I only nodded (a nice neutral response) he said, “you noticed that I said a certain freedom. Freedom doesn’t exist outside of us; it needs to be created. It can be created anywhere though, in every little town that these two highways run through or even beneath the yoke of tyranny–it doesn’t matter. Walking down the road every day is a fast way to manifest this freedom.”

“So, you’re saying that hoboing is an example of a larger freedom and that one can search for this freedom merely by participating in it?” I said in my best psychologese.

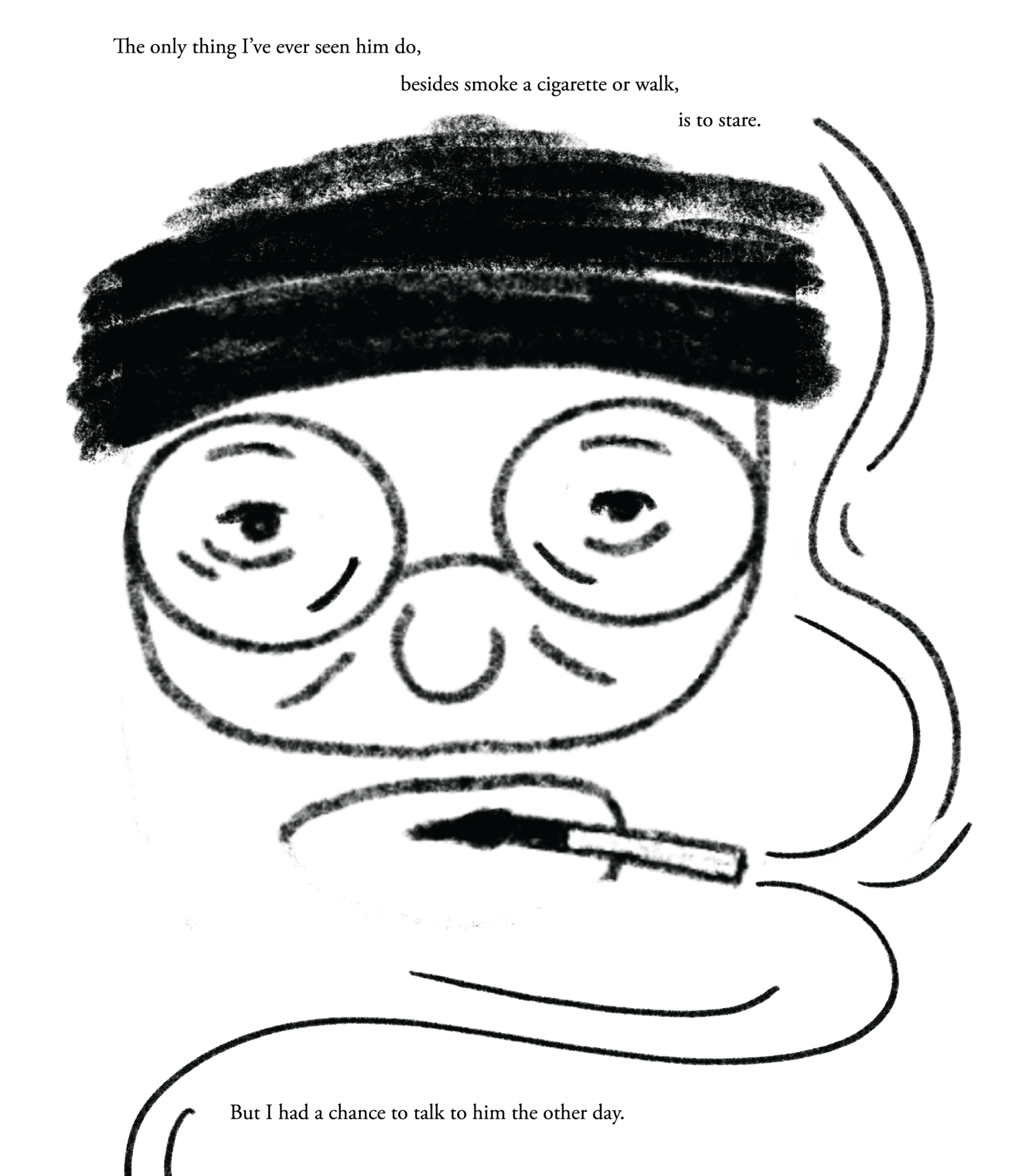

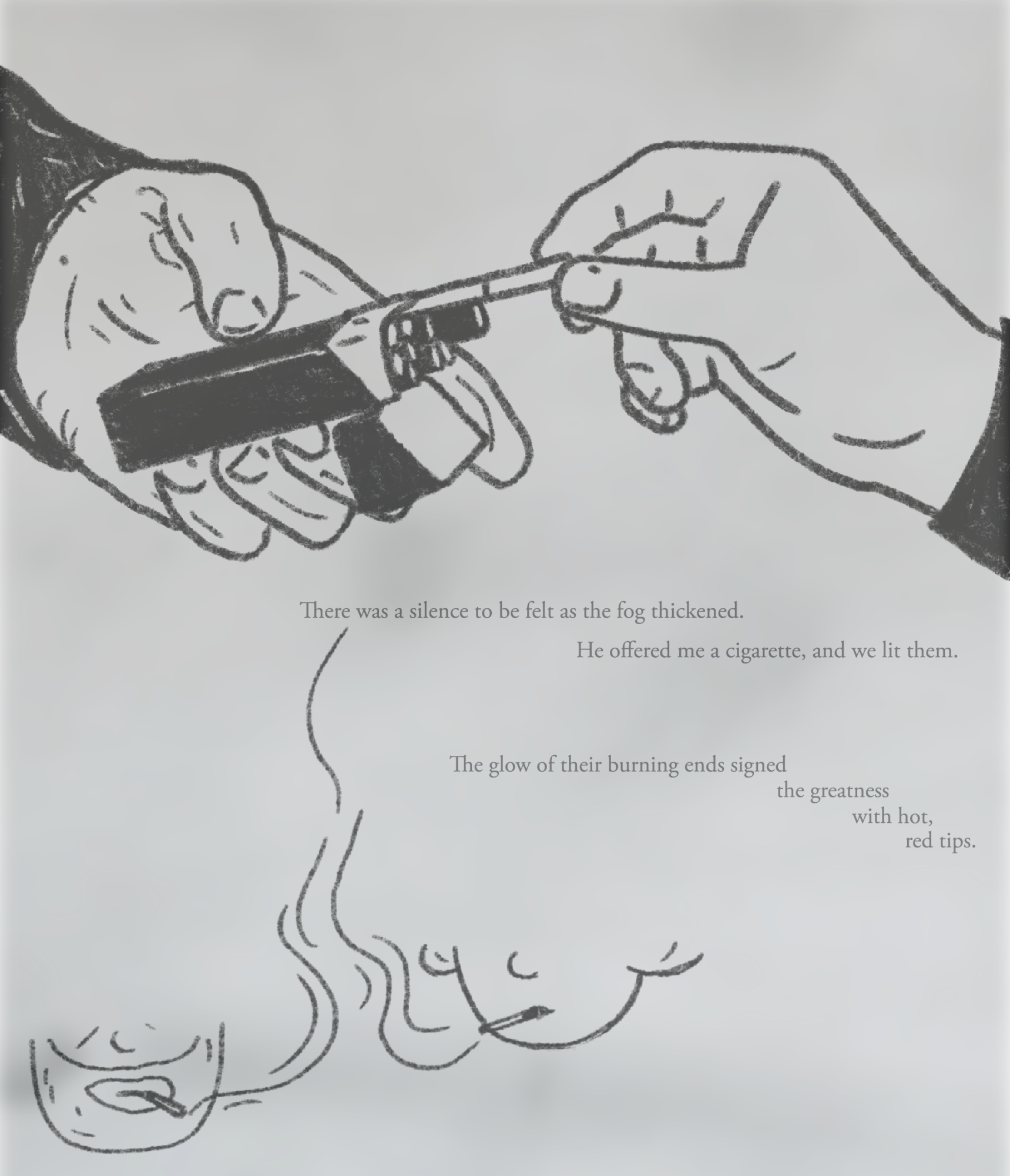

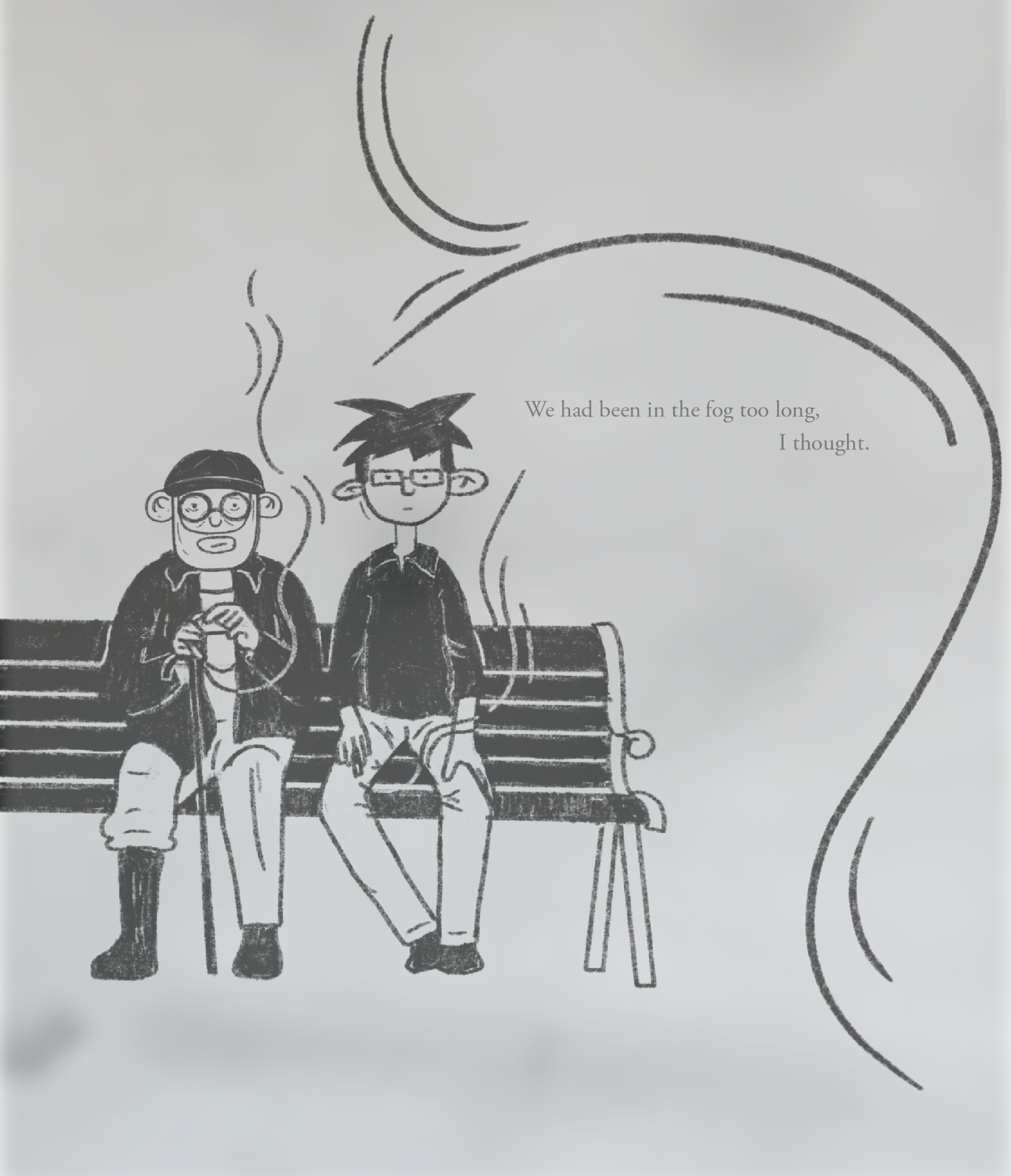

There was a silence to be felt as the fog thickened. He offered me a cigarette, and we lit them. The glow of their burning ends signed the greatness with hot, red tips.

“Freedom is an act,” he offered. “It’s not an idea as such. It is a timeless act created anew, everyday, by every man, woman, and child in their own situation. For me, walking these roads is an act that I have found to be a meditation to be free. You ever hobo or hitchhike?”

“Some,” I replied.

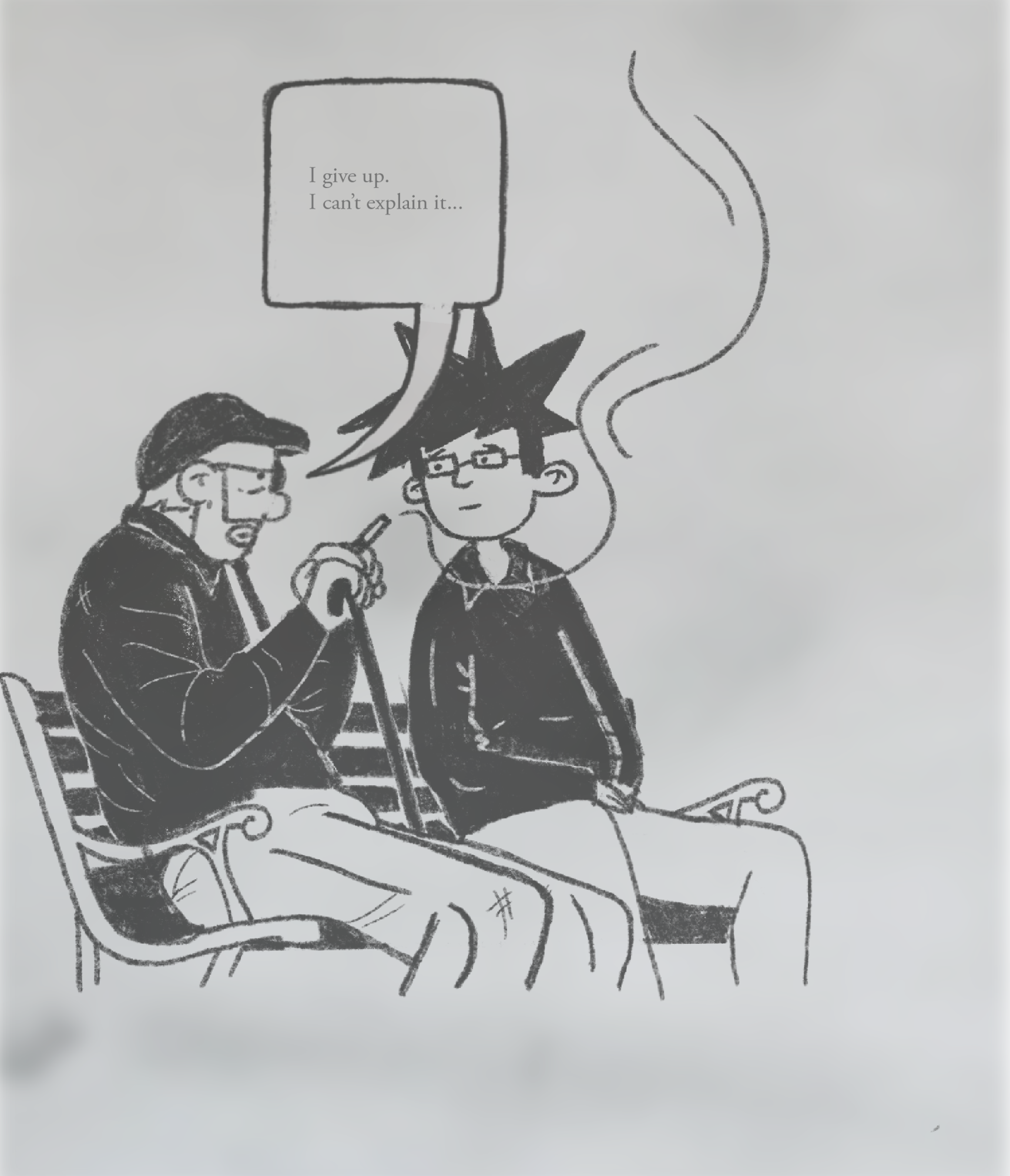

“Well it’s in these situations–because people have always wandered–that freedom comes closest to being defined as a specific act.” Raymond Etoile was animated. He was onto something very encompassing yet felt the frustration of not being able to express it.

“I give up. I can’t explain it,” he said at last. “Freedom can be found where you look for it. I can only tell you of the specific freedom that I’ve known. I walk the streets trying to explain it to myself.”

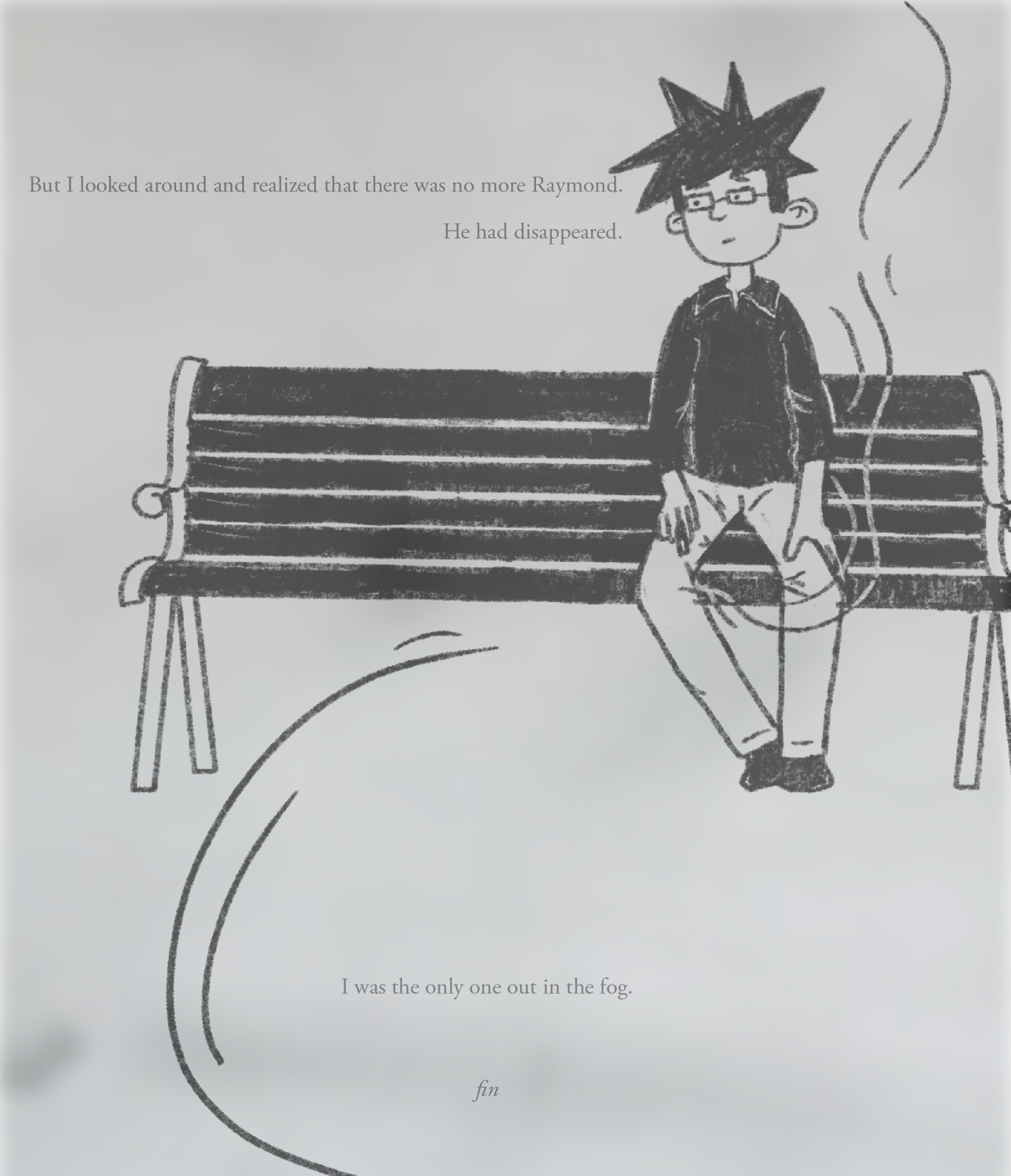

Raymond was too vague for me. He was as specific as the fog about his specific freedom. We had been in the fog too long, I thought. But I looked around and realized that there was no more Raymond. He had disappeared. I was the only one out in the fog.