Approximately 19.5% of the United States population is of Hispanic descent. According to the 2023 census, the exact statistic hovered around 65.2 million people, making the group the largest ethnic minority in the U.S.

Common sense would suggest a community so large and consisting of people from numerous, distinct international origins would be just as diverse in its identities, customs and livelihoods — and it is. However, a pervasive and long-standing tendency to homogenize the nuances of Latino cultures in the U.S. persists, and it needs to be addressed.

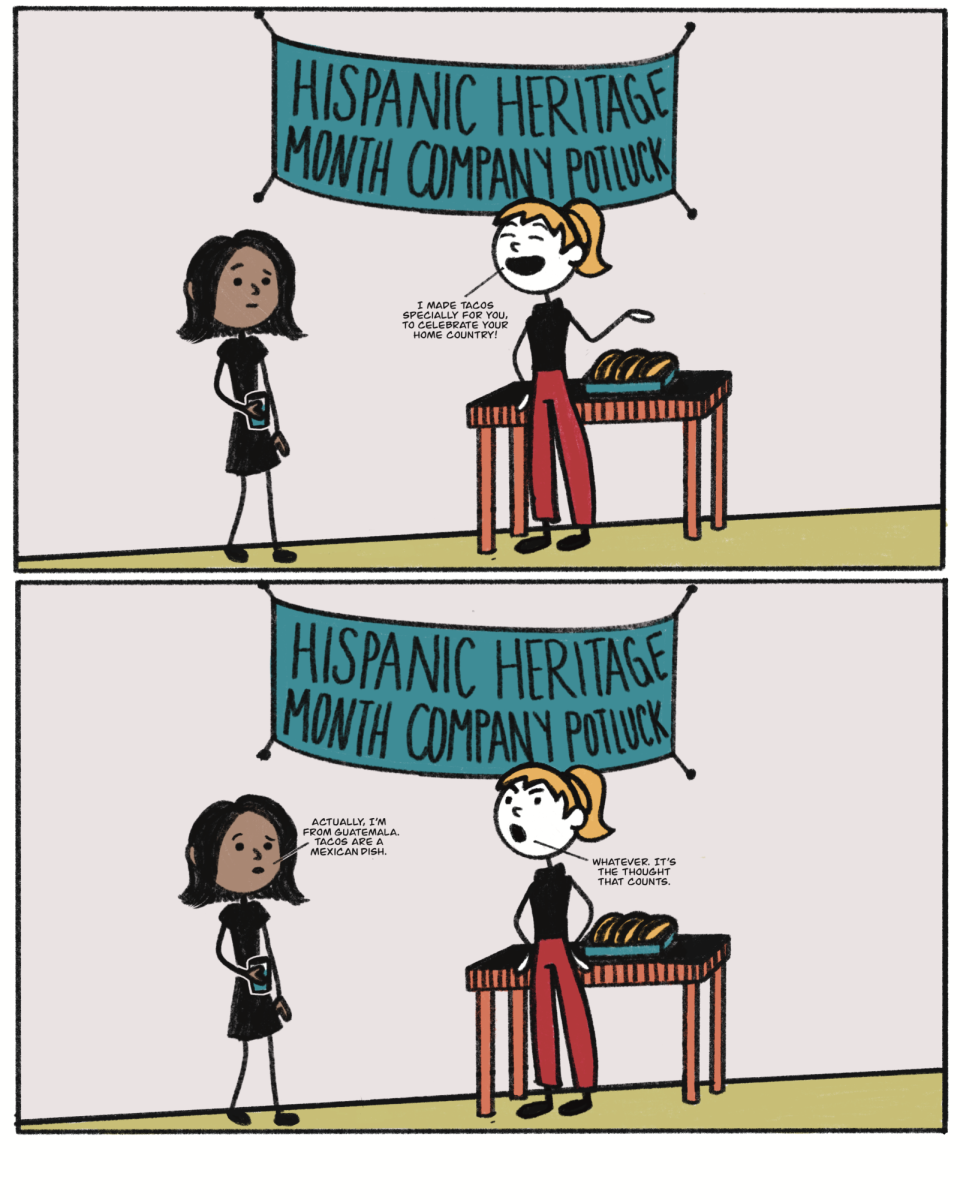

The Latino monolith is a term used to describe the falsely perceived mass-collective of uniform values, backgrounds, interests and ideologies attributed to the millions of U.S. residents whose ancestries can be traced to one of the many countries that make up Latin America.

Whether it be through pandering, tokenization or stereotyping in the media, the Latino monolith has infiltrated mainstream U.S. society for decades, resulting in a widespread reductive lack of understanding when it comes to the complexities of Latino identities. These generalizations only limit the voices and opportunities of the people they belong to.

U.S. politics are notorious for this type of manipulation. Informally deemed “Hispandering,” politicians have a long history of selectively appealing to Latino voters as a campaign strategy, specifically because of their significant influence on election turnout.

Common trends within this practice include speaking sentences in Spanish and posing for pictures at popular Hispanic restaurants. At a 2015 “Latinos for Hillary” organizing event, former first lady Hillary Clinton famously told a crowd, “I’m not just La Hillary — I’m tu Hillary.”

In Hollywood, movies and TV shows are similarly infamous for their weak attempts at Latino representation. Characters with geographically distinct family origins commonly become oversimplified and lumped together, often having identical accents, professions and family lives.

The tendency to dilute and fuse the identities of Latino characters fuels the entertainment industry’s other problem with Latino representation: stereotyping. Characters without distinct backgrounds, goals and cultural participation are easier to push into supporting roles, all too often manifesting in the form of domestic help and criminals.

The ignorance these instances of tokenization and downright racism produce in the minds of those outside Latino communities, while insidious on its own, drives other, much more systemic issues. By obscuring the naturally nuanced fundamental needs, interests and values of the different cultures that make up the greater Latino community, those with power create a society wherein the resources and opportunities optimal for a significant percentage of the country to thrive are nonexistent.

Meanwhile, data supports what public institutions neglect to recognize. According to poll records, the way Latinos weigh issues like gun violence, reproductive rights, housing costs and healthcare ranges significantly. The way the community engages directly with healthcare, the economy and education is also extremely diverse.

A report from the U.S. Census Bureau shows that between 2005 and 2021, all Hispanic populations in their data set saw an increase in college or graduate school enrollment but at different rates. Among the most explicitly described groups, Cubans had the highest enrollment rates overall with Dominicans and Puerto Ricans seeing similar growth rates. The rise in Mexican college enrollment between 2005 and 2021 was the most significant — almost twice that of Dominican enrollment.

Though ironically oversimplified, studies like this provide a rough idea of how diverse the Latino community is in their decision-making and in their access to certain resources. They also help support why more, considerably detailed studies about this diversity are necessary.

In order for the perception of the Latino monolith to be appropriately dismantled, decisions on how systems can be changed to adequately serve Latinos should be left up to those within the community themselves.

Additionally, those outside of the community and especially within fields of public influence like science, journalism and politics must work to expand coverage and general understanding of the cultural gradients within Latin American heritage so that public information about this diversity becomes more accessible.

If non-Latino politicians, educators, creative directors, economists and doctors better understood the diverse realities of the Latino community — by way of listening to their individual experiences, values and needs — perhaps fundamental U.S. institutions could begin to more accurately reflect and serve a wider breadth of constituent concerns.

A country well-suited to support the different needs of its people starts with leaders who are willing to understand and work with those different from them.