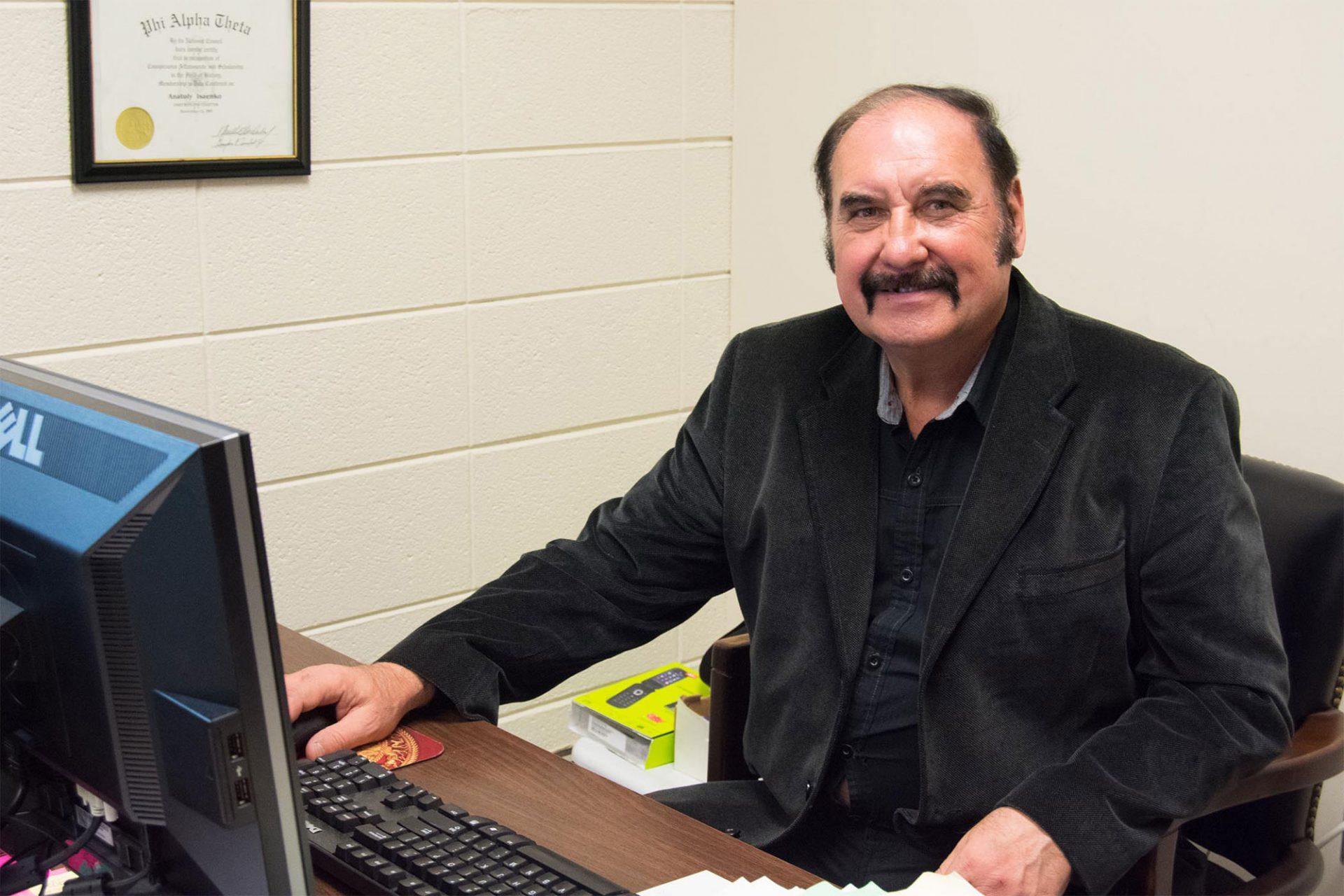

Anatoly Isaenko sat at his desk clad in jean from head to toe, sporting a handlebar mustache and talked through a thick Russian accent for hours about life in his home country. During the span of almost seven decades, Anatoly Isaenko has seen the end of Stalin’s regime, the end of Soviet Russia and the beginning of Russia’s democratic society.

Before moving to America, Anatoly Isaenko said he was instrumental in the democratization of Russia after the resignation of USSR leader Mikhail Gorbachev, which consequently led to the fall of Soviet Russia in 1991.

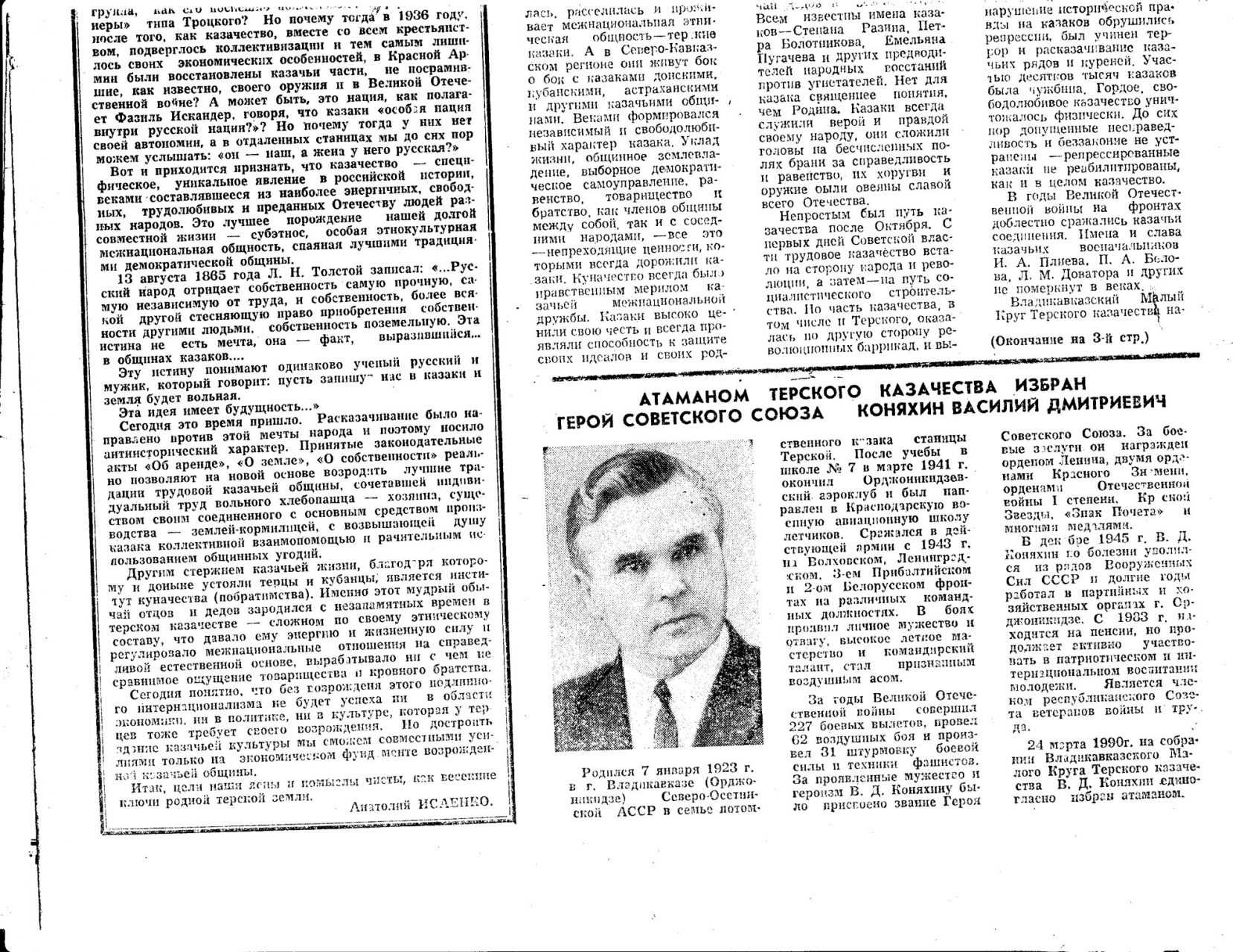

Some of Anatoly Isaenko’s accomplishments included writing the regulations for the new democratic government, establishing and joining its new congress, co-editing and writing for its first democratic newspaper titled “Rebirth of the Terek Cossacks,” and the list goes on.

“Of course I joined with these people who were building a new democratic state,” Anatoly Isaenko said. “I was adviser to the president, to parliament and headed this movement of my people– Cossack legal rebirth!”

However, as a result of decades of war against ethnic minorities by Russian elites, tensions began to rise during the ‘90s after the collapse. Because of these strains, Anatoly Isaenko said Chechens, an Islamic minority group in Russia, targeted him as a prominent figure of the new movement for legal rebirth. As a result, he and his family were forced to risk going west to America in 1995.

They fled with the help of a colleague with only $200, the clothes on their backs and the luggage they could carry. Among the 23 other members serving on the congress Anatoly Isaenko helped to create, 19 were killed and their families were abused, Anatoly Isaenko said.

“History cannot be separated from the history of me and my family,” Anatoly Isaenko said.

One of his sons, Sergei Isaenko, commercial photography adjunct professor at Appalachian, said he vividly remembers the journey of escaping from Russia to America. He described it as jumping through a portal into a new world.

With Sergei Isaenko in his late teens, the move added confusion during a time when most American students his age were worried about college rather than running from terrorism, Sergei Isaenko said.

“Moving away from my home city and home country was an incredibly dramatic experience bound for another world, another universe,” Sergei Isaenko said. “But one of the biggest highlights of arriving to another country was the sensation of culture shock.”

In contrast with what Sergei Isaenko was used to in post-collapse Russia, America represented wealth and abundance, Sergei Isaenko said. There was an abundance of food, streets were clean, there were manicured lawns for every home and roads were devoid of any potholes. America freed them from constant persecution and provided a quality of life that Russia had deprived them of, Sergei Isaenko said.

“In comparison, my world and childhood was filled with grim memories of war,” Sergei Isaenko said. “But it took years to adjust. Still to this day, I don’t completely fit into this culture and never will. I will always carry a hole inside of me that represents what the life behind the wall took out, and the scars it left on the inside of my soul.”

For Anatoly Isaenko, the move meant a second chance.

“From zero I rebuilt my career again,” Anatoly Isaenko said. “I am proof of the American dream.”

Anatoly Isaenko is currently a historian and history professor at Appalachian. His primary focus is in ethnic conflict among persecuted minorities, especially in Russia.

“From elementary school, I knew I would be historian,” Anatoly Isaenko said.

Upon graduating from North Ossetian State University the dean offered Anatoly Isaenko the opportunity to obtain his doctorate at Moscow State University.

At Moscow State University, Anatoly Isaenko obtained his doctorate in world history but also received what he calls a “parallel education” that threatened the line between life and death. In addition to religious reading on the Puritans, Anatoly Isaenko was given prohibited titles by American authors and more censored readings from authors around the world that threatened allegiance to the Russian government at the time.

Despite the amount of persecution he endured, Anatoly Isaenko said his love for history and learning has never wavered. He said this passion comes from his childhood, when his father and brother in arms would spend hours recollecting adventures during their time in the service.

Anatoly Isaenko would listen in on these conversations and become inspired.

Coming from a long line of military service there was never a shortage of war stories in his home. His family heavily participated in the military on both anti-communist and communist fronts, Anatoly Isaenko said. He has known both sides of Russia’s history, which he said often disproportionately advantaged Russian elites over ethnic and religious minorities.

As a professor, Anatoly Isaenko brings to life examples from his memory in the classroom. He integrates vivid stories that reveal the multifaceted reality behind Russia’s closed doors during his lessons.

Doctoral candidate Evan Wallace said he sees Anatoly Isaenko as one of his main mentors and even made the decision to move from Florida specifically to complete his master’s thesis under him. Wallace was intent on studying ethnic trauma and said he could not think of a better advisor.

“When I was initially performing my research, I was constantly following new trails and leaving topics behind, but he never grew frustrated,” Wallace said. “His patience and passion for his discipline created an environment which allowed me to flourish.”

Anatoly Isaenko said that he will continue to teach issues such as the themes behind revolution and conflict throughout history because they put into perspective the “psycho-historical underpinnings” of conflict. By learning about these topics now methods of prevention are tangible, Anatoly Isaenko said.

Story and photo by: Savannah Nguyen, A&E Reporter

Newspaper scans courtesy of Anatoly Isaenko

Featured Photo Caption: Anatoly Isaenko poses at his desk on March 19. Isaenko is from Russia and is a professor in the Department of History at App State.