Appalachian biology professor Jennifer Geib recently co-authored a report published in Science Magazine that demonstrated a link between climate change and the tongue lengths of bumblebees.

Interest in the report initially coalesced around the movement of certain species of bumblebees to higher climates in the Rockies. When studying that movement, researchers found that the tongue lengths of bumblebees in those regions were dramatically reduced over 40 years, a blink of an eye in the context of evolutionary biology.

Nicole Miller-Struttmann, a biology professor at the State University of New York College at Old Westbury, said that they came in with several different ideas about what could be driving the shift before settling on climate change.

At the time of publication, the report said there has not been any change in the ratio of flowers with longer corolla tubes, which are favored by long tongued bees, but the amount of flowers has declined generally as a result of warmer summers.

“We had noticed in a different analysis with a different set of data that flowers in general were declining, and that that was related to climate, and knowing what we know about plant pollinator interactions that led us to seeing the connection between tongue length and flower density,” Miller-Struttmann said.

Geib said having less flowers to choose from, the bees probably found more success with traits that allowed them more access to nectar, causing the more specialized long tongued bees to be weeded out.

“Literally millions of flowers have been lost since the 1960s and ’70s,” Geib said.

But Geib said the report has an optimistic slant, by showing the resilience of bee populations when faced with the effects of climate change.

“If they can adapt to forage on the flowers that are remaining it’s actually a hopeful sign for them in dealing with climate change,” Geib said.

Geib said there is still speculation on how the long tubed plants will be affected but given that these plants can live for 80 years as compared to bumblebee populations, which are reborn in a year, any consequences will play out over a longer timeline.

Geib said the study attracted considerable attention because it is one of the first to demonstrate a link between human driven climate change and natural selection leading to a shift in traits for a population.

The report used data collected by researchers in the field over the last 40 years, which Geib said was instrumental in completing the study.

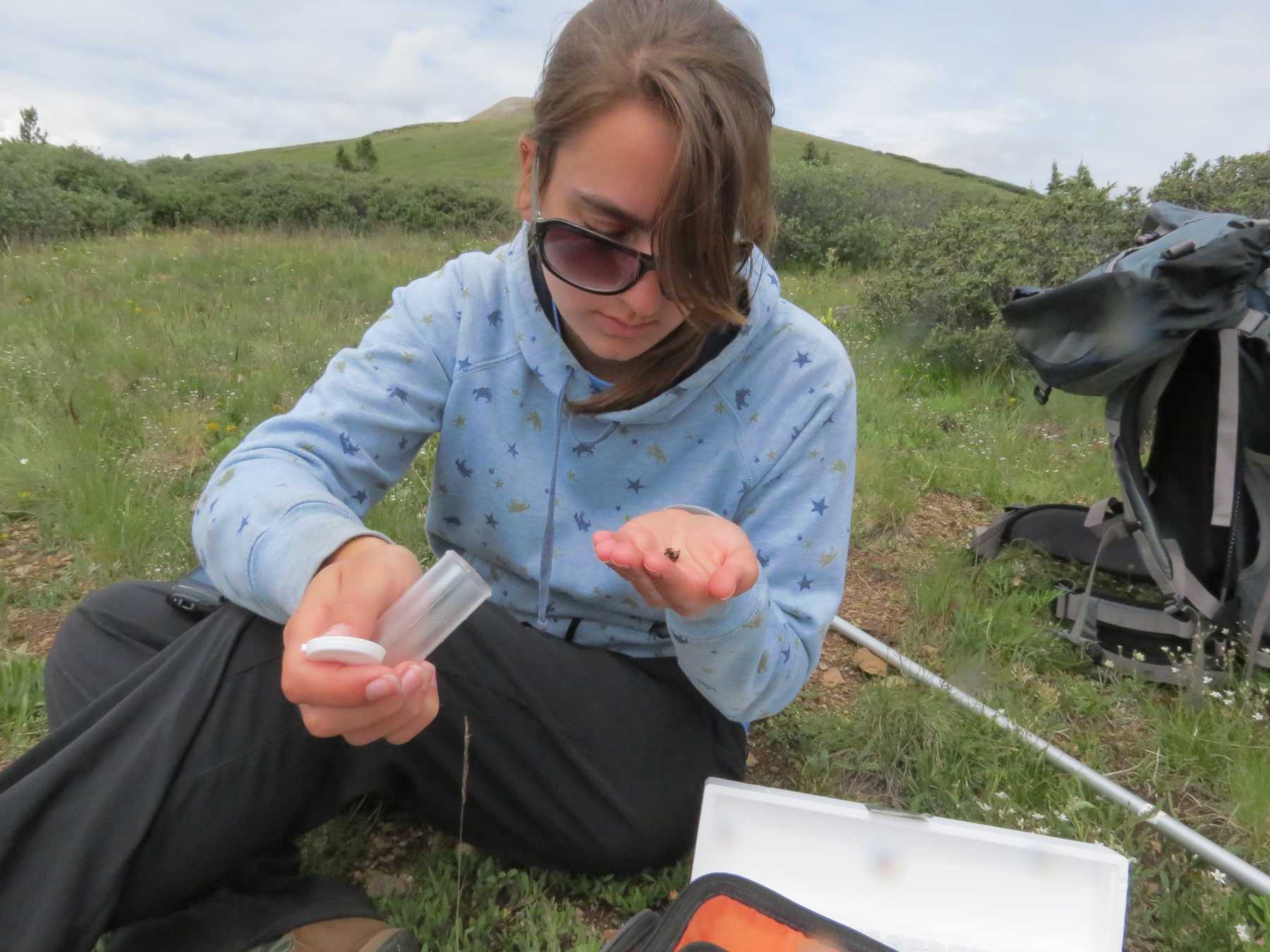

Miller-Struttmann said that in order to study the current population of bees, researchers would hike through the Rockies and collect bumblebees.