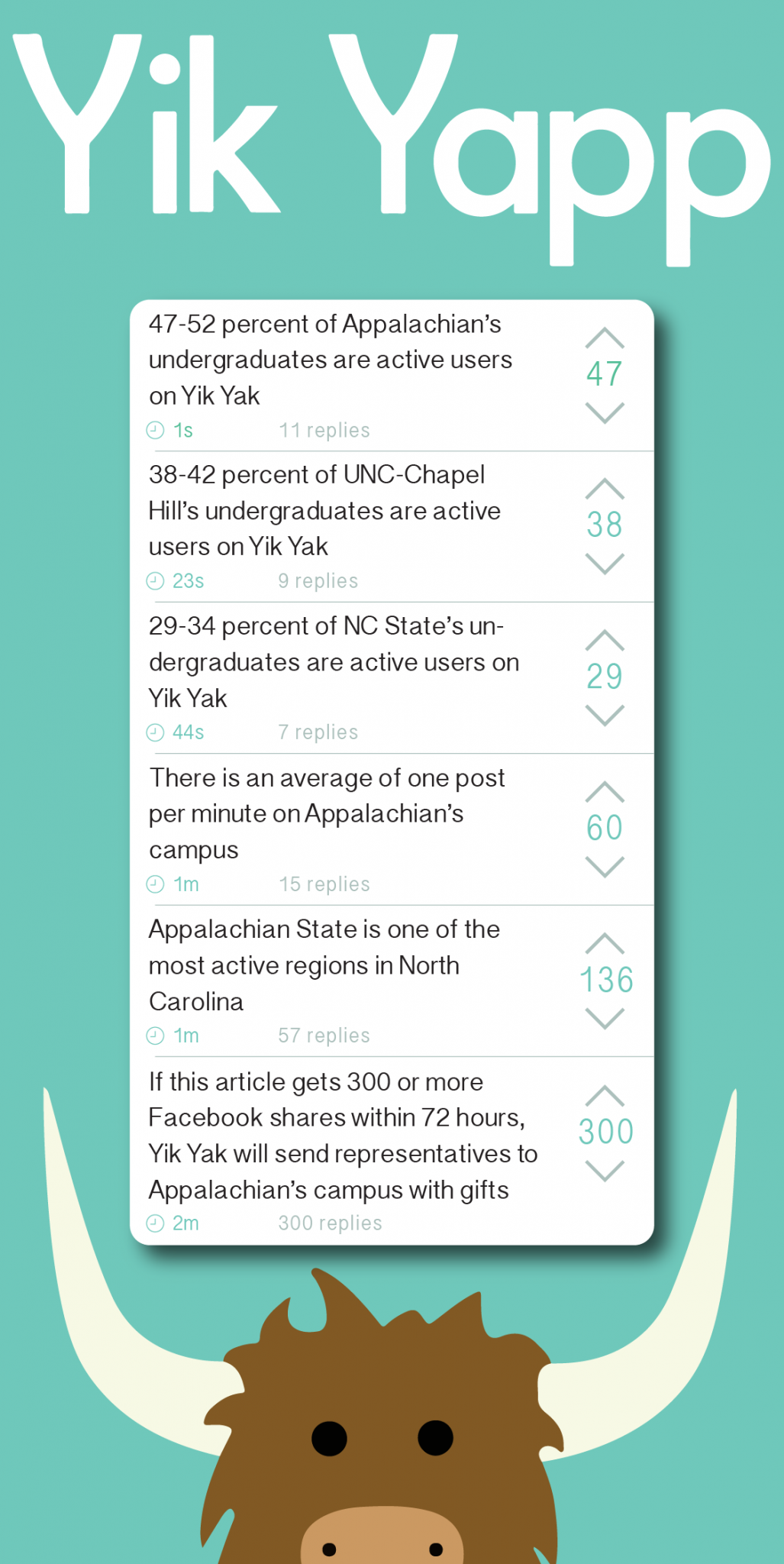

Video: Yik Yak is an anonymous social networking app that allows the user to post messages on a location-based feed. It has become very popular on college campuses. App has one of the most active regions in the state with 47-52 percent undergraduates being active users.

Yik Yak, the popular anonymous social network that allows users to see and post messages within a one and a half mile radius of their phone’s location, has gained rapid popularity on college campuses in the past year.

Universities have served as hubs of traffic for the iPhone and Android application, as dense populations keep the feed moving.

On Appalachian’s campus, more than 47 percent of the school’s population uses the app, with new posts added about every minute, said Trish DaCosta, who handles Yik Yak’s media relations.

“Yik Yak works really well at colleges,” said Cam Mullen, the lead community developer for Yik Yak. “On a campus it works because everyone who has Yik Yak pretty much is a student – they all have the same inside jokes and the same problems, so they really can identify with each other and the content is really relevant to what’s going on in their lives.”

This creates what Mullen calls “sticky” content – that is, messages that are relevant and rapidly changing, as users vote posts up and down on the main feed. This feed is then reset about every hour on campuses as popular as Appalachian’s.

Although the app was first intended to be used as a sort of online bulletin board, the anonymous aspect has led to many other uses – mostly jokes on Appalachian’s campus – but also bullying, sexual meetups and warnings about undercover police. Although the app has been banned in high schools through location-sensing “geo-fences,” some aspects of immature bullying still carry over to universities.

“It is unfiltered, unbiased opinion and it’s incredibly quick,” Mullen said. “When there is something dramatic that happens on campus, within seconds people are talking about it on Yik Yak, which is way quicker than any reporter could put together an article.”

Mullen said he was unaware of the use of the app for uses like evading police, but said that sort of use is evidence of the community standards the app tends to cultivate on college campuses.

“We want to support discussion that we are all supporting each other and staying positive,” Mullen said. “We want it to be as healthy and entertaining as possible.”

Mullen said he encourages people to use the network to meet up with each other and to voice their opinions without the fear of being judged, although their terms of service that each user must accept specifically prohibit any post that serves to “defame, abuse, harass, stalk, threaten, or otherwise violate the legal rights – such as rights of privacy and publicity – of others” or “discuss or incite illegal activity.”

One way they try to combat this is through user-generated votes – at a score of negative five, a post disappears. Everything else is ranked by points, which are reset periodically. Additionally, a team of moderators and scanners search for racial slurs and identifying information to use to suspend and ban users who might be abusing the system.

These measures do automatically look for phone numbers, but can’t yet track other more evasive information like Snapchat or Twitter usernames.

Junior nutrition and foods major Caitlin Peterson witnessed an exchange on the app last week in which a student posted about being alone on her birthday, and another user spotted it and ended up taking her to IHOP.

“No worries, I won’t kidnap her!” the post warned at the time. Both users ended up posting again after the fact to verify that they did meet up, Peterson said.

An anonymous user who contributed to this article via the app reported once seeing a post by someone threatening suicide, which then received over 100 comments until users got some identifying information from the poster. The anonymous user texted him all night until hearing back that he was safe in the morning.

“Yik Yak saved a life,” a user said.

“It’s not all trash-talk and negativity,” another said in response.

“I use it to ask questions, to maybe find a study buddy, a ride or even a massage,” an anonymous female freshman said. “Usually though, to post my random stupid thoughts that aren’t worth texting a friend.”

She said she once posted a yak saying “I would pay someone for a bomb massage,” and used the app to negotiate a time and a meeting place.

“I get my roommate to accompany me downstairs just to be safe and this guy ends up being the cutest ever. So I bring him up and he then massaged my entire body for about two hours while my roommate and I watched ‘Pretty Little Liars,’” she said. “Nothing sexual happened and we are still friends.”

Story: Lovey Cooper, Senior A&E Reporter

Inforgraphic: Malik Rahili, Visual Managing Editor

Emily Cooper • Nov 12, 2014 at 5:47 pm

Interesting! Sort of a return to the pre-Facebook internet.