Over the course of the academic year, nine students have died at ASU

Right outside of the Student Development office, Cindy Wallace walks by a sizable list of student names every day.

As she scans the names mounted on a plaque on the first floor inside the B.B. Dougherty Administration Building, the vice chancellor skips randomly from name to name, pointing to a student she met once or knew very well. Wallace will say something she remembered about them, doing so with a nostalgic smile on her face as she remembers each student differently.

And then, with a slight change of tone and mood, she recalls how these students passed away, the reason why their names have been given a spot on the wall.

The more than 150 names on the Appalachian Student Memorial Plaque immortalize the students who have died, on- or off-campus, during their time at Appalachian State University since the plaque was created in September 2001.

“When you know the student individually it’s even harder,” said Wallace, who has been in Student Development for 11 years and worked in academic affairs prior to that. “There are any number of cases where I have known the students personally. I have taught them, I have advised them in a club or an organization, and that probably is a whole ‘nother depth of kind of sadness.”

The most recent names added to the memorial, which now spans across three boards, are four of the students who died during the fall 2014 semester, including freshman Anna Smith. Altogether, nine students have died this academic year with the most recent death of senior Michael Cameron Schmitt on Jan. 30.

This number may seem higher than what has been reported in the media in the past few months, but that could be due to the fact that the university will not release the names of currently enrolled students who died if the family decides to withhold that information.

“I think that as a university community we all want to know what took place and transpired when we lose a student, but I also respect the family’s decision to keep that private, should they choose to do so,” said Dean of Students J.J. Brown, who has the responsibility to communicate with the families of students who have died.

In recent years, eight students died between the fall 2012 and summer 2013 semesters, while seven died between the fall 2013 and summer 2014 semesters, according to numbers provided by the Office of the Dean of Students.

“[W]e don’t anticipate, no one does, that going to college involves that sense of loss,” Wallace said.

The current state at Appalachian

Brown has been working in higher education for 20 years. In the span of those two decades, Brown said the disappearance of Smith and the three deaths that took place within the span of one week in January were some of the most difficult challenges he has faced in his career.

“The impact this year has been significant and certainly with the loss of Anna, I had never experienced a search for a missing student that extended the way that did and how that permeated and touched all of us in different ways,” Brown said.

Smith’s disappearance was reported by the university Sept. 4 after she had not been seen in her residence hall since two days prior. The search for her took place for more than a week until her body was found in a wooded area not far off of campus Sept. 13, according to reports from The Appalachian.

It wasn’t until November that the North Carolina State Medical Examiner’s Office ruled her death as a suicide, according to a press release from the Boone Police Department.

There are some deaths this year that were labeled as unattended deaths, including those of freshmen Jeremy Sprinkle and Mary-Catherine Johnson, who were found on-campus in Lovill Residence Hall and the Appalachian Panhellenic Hall, respectively. The official causes of death for these cases are still pending investigation.

“Unattended death” is a law enforcement term that is applied when there is no sign of foul play. The term could mean anything from suicide, drug overdose, natural causes or an accident.

“Unattended death is the term that most law enforcement agencies would use, unless we knew it was a homicide, as an example,” University Police Chief Gunther Doerr said.

But the term can come with some confusion, concern or assumptions until an official cause of death is determined by a medical examiner.

“That delays things and that makes it harder to feel comfortable because you don’t know what unattended death means, and even the police don’t know,” said Dr. Dan Jones, director of the Counseling Center. “They might guess at what happened, but until there’s an autopsy it’s not a fact.”

While only Smith’s death has been officially ruled as a suicide, that issue has become a prominent topic at Appalachian this year.

Suicide, which is the second-leading cause of death among college students — car accidents are the leading cause — can have a number of factors attached to it, such as mental illness or stress in a new environment. Most mental illnesses, such as depression, anxiety or schizophrenia, typically manifest between the ages of 17 and 24, Jones said.

And while things may have been very manageable in high school, the added freedoms and unstructured environment of college can be a shock to some students.

“It’s an unstructured environment and you have to make decisions and discipline yourself, and some students have never had to struggle,” Jones said. “Some students have never had to feel uncomfortable.”

Anything from a first major breakup and feeling broken-hearted to failed assignments can trigger symptoms of depression, Jones said, including change in sleeping habits, loss of appetite, a loss of interest in things that used to interest them, loss of motivation and suicidal ideation.

Jones said Smith’s disappearance and apparent suicide at the time of her discovery seemed to set a tone for how the news of the following deaths this year would feel to the university.

“Nobody knew where she was at, and that disappearance seemed to have more fuel to it than the other deaths because nobody knew what was going on,” he said. “To have something like that start off the year and then have multiple deaths follow that, I think made it darker and more emotional because of the way things started off.”

Carson Rich, Student Government Association president, said he’s struggled this year thinking of how students can cope with the news and reality of the deaths that have taken place.

“We’re not clinical psychologists, we don’t have degrees in student development,” he said. “We don’t know how to professionally deal with situations like this.”

Rich expressed concern that the high frequency of deaths this year could potentially result in a sense of numbness on campus.

“I think that we’re kind of getting into a scenario where sadly these student deaths are becoming so normal that one will happen and then we just wake up the next day, go to our 8 a.m. [class] and act like nothing occurred,” he said. “And that’s not how I want this environment to be shaped just because it’s never affected my personal life.”

Communicating, notifying and remembering

Anytime an enrolled student passes away, on or off campus, the university has a system for notifying certain people within administrative levels and — if that information can be shared — to the campus community.

The process begins with university police, who are either contacted by an outside law enforcement agency if the incident took place off campus, or will begin the investigation themselves in the case of an on-campus situation. After family has been notified of the passing by the police, university police will communicate with Brown, who will then reach out to the families to how the university can assist them, Doerr said.

“And then we would make sure that the administration was notified in the case of the vice chancellors and the chancellor,” Doerr said.

In some cases, a family might not want information about a student’s death to be released by the university, which has happened this academic year. In these instances, Appalachian will respect the family’s wishes and refrain from releasing information to the campus community.

While Doerr said university police would not release the name of a student without knowing the family had first been notified, there are scenarios where they would release details in the aftermath of an incident on campus in the case of rumors or social media “triggering a whole lot of potentially incorrect information.”

“We might do an alert to the campus without a name just to clear the air that there was no foul play involved and that there was no threat to the campus community to make sure everybody is not getting some misinformation and reacting unnecessarily,” he said. “But again, we would withhold that name until we were sure that the family was notified first.

Micki Early, who handles special projects in Student Development, is in charge of putting together the announcement of a student’s passing, getting the memorial book for students to sign in Plemmons Student Union and managing the names on the memorial plaque. Early said she can understand why families would not want the student’s name or information released in the aftermath of their passing.

“Personally, I would feel like it is just too hard to even talk about or to put out there for anybody,” she said. “They may not be able to relay their feelings at that time, so much less put it out for everybody.”

Even if a student’s name is withheld from a campus-wide announcement or if a memorial signing book is not placed in the student union by the family’s wishes, their name will more than likely be hung on the memorial plaque in the administration building.

The Appalachian Student Memorial Plaque was created in 2001 in conjunction with Barbara Day, the dean of students at the time, and parents of students who had passed away. Families are invited back to campus every year for an annual Memorial Program in B. B. Dougherty to honor the memories of students who have passed away while enrolled at Appalachian.

“I always tell the families that no matter what these circumstances, they will always be a Mountaineer,” Brown said. “It’s part of what we do with our memorial program, is that they will always be a Mountaineer, and I think that’s really, really important.”

Counseling and coping

For anyone affected by the deaths this year, there are resources both on and off campus to assist them.

The Counseling Center has walk-in hours Monday through Thursday from 1-4 p.m., Tuesday and Wednesday from 8:30-10 a.m., and Friday from 1-3 p.m. Since last semester, the center has seen an increase in walk-ins, counseling sessions and after-hours emergency phone calls.

But the center is always readily available to students in the case of an emergency. Jones said if a student came and communicated a sense of urgency to the front desk, anyone who was not with a client or otherwise engaged in a meeting would drop everything to provide help for that student.

“One of us would cancel that appointment and see you,” he said. “We always respond to emergencies.”

Students can also be connected with a counselor after hours at any time by calling University Police. If there is a situation that counseling services on campus cannot fully address or needs additional help, Jones said the Counseling Center will make referrals to resources off campus.

“If we can’t help them, then we’ll find somebody who can because we know how to assess and refer,” he said.

Among those services outside of the university is Daymark Recovery Services, which provides “psychiatric services for the treatment of a mental illness, substance abuse problem or developmental disability,” according to its website. Daymark’s Watauga Center is located in Boone off of the Poplar Grove Connector.

In addition to counseling services is App Cares, a mobile application that contains resources for student health and safety. The app, which is free for iPhone and Android devices, includes contacts and information for police, safety and counseling, as well as suicide and assault hotlines.

For faculty and staff who might be facing some of the same struggles and challenges as students, a counseling center is available to them as well.

For many people, the simple company of others can aid in the grieving process. Rich said whatever a person’s support system is — family, faith, friends or anything else — they should find that system and use it.

“For me, I’m in a bible study,” he said. “I would go to them and I would express that I’ve been really down in the dumps and I’m just having a hard time figuring out how I’m doing.”

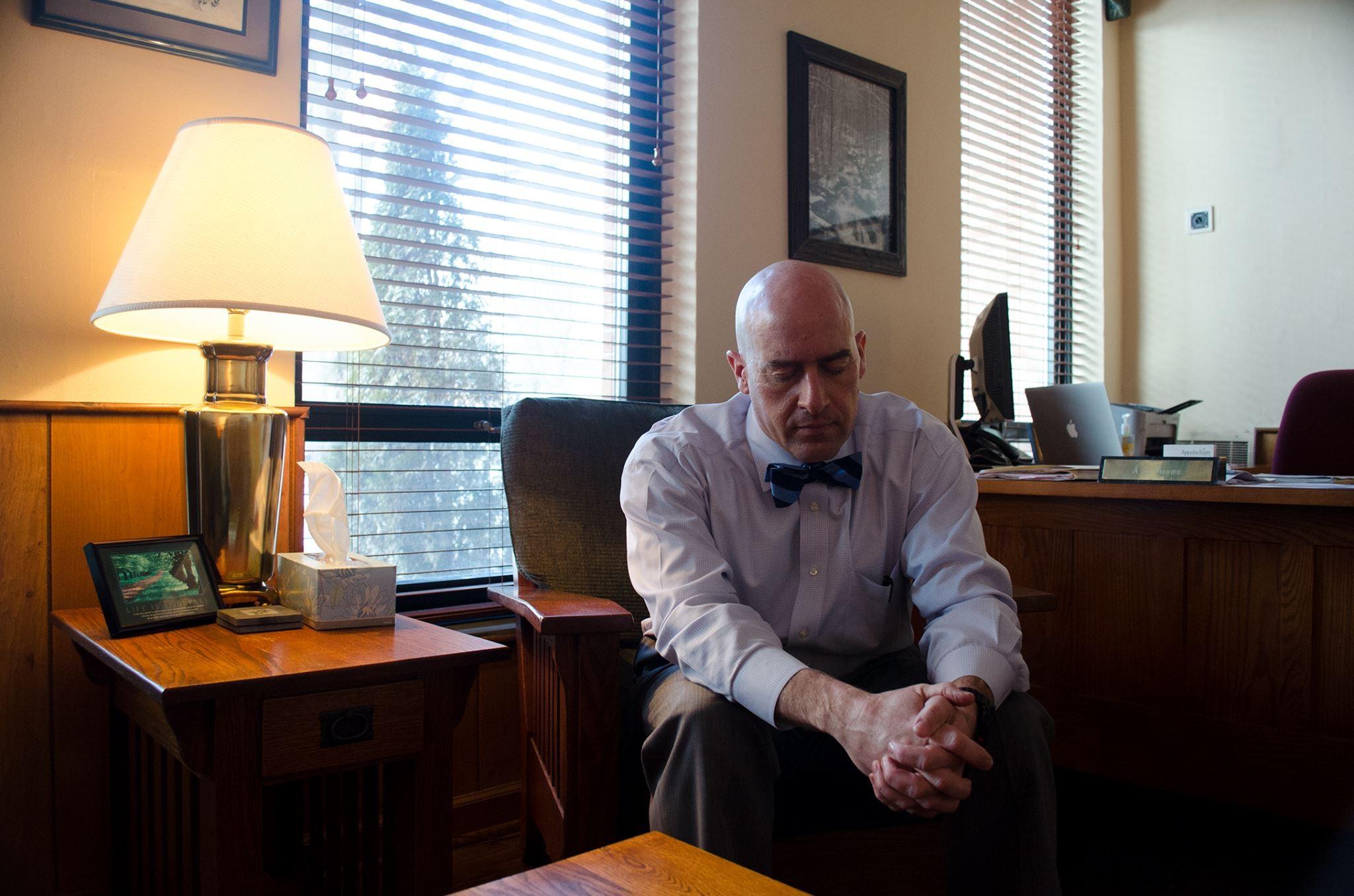

Brown has different ways of coping with the news of a student death and how he processes it. When he’s in his office, he’ll often close his eyes and reflect on the news and the family of that student.

“I’m just going to close my eyes for a second and take a deep breath and think about what I’m always thinking about, is that family and the news that they’re going to get,” he said. “I’m thinking about what that means and what that looks like.”

But when he comes home from a day like that, Brown just wants to hug and kiss his boys and tell them he loves them.

“It hits home in a different way as a parent for me personally than it used to when I wasn’t a parent,” he said.

One of the ways Wallace believes in addressing loss and grief is to look for the positives in life.

“Grief makes that really hard to do because you have that dailiness of missing somebody, particularly if you knew them closely,” she said. “But the positive things on a college campus always far outweigh the tragic.”

As the name plates for the other five students come in over time, people will continue to pass the memorial plaque every day, including Wallace. Anyone who looks at the plaque may not know as many of the names of the students or have the connections that Wallace has had with some of them over the years, but their names will nonetheless forever be enshrined in their memory on Appalachian’s campus.

Story: Michael Bragg, Enterprise Editor

Robin Gallagher • Feb 11, 2015 at 5:54 pm

I can’t help but have tears in my eyes when I read this edition. May all the App families have peace, may our sons and daughters be safe, happy and blessed. They are our world’s future.

Jeanette Avery • Feb 10, 2015 at 7:32 pm

very nicely done. thank you

Susan Keck • Feb 10, 2015 at 7:29 pm

I saved my daughter who was locked up in her room, not attending classes. If it wasn’t for her roommates telling me at the final moment that she had no friends and that she was not attending classes, or finals or meeting new friends, we would have never known what was going on. I don’t understand that if the teachers notice something about a student that they don’t reach out. I also don’t understand when I made her come home, that no one frome the community has called her. She was going to the medical facility twice a week and because of HESPA, she wasn’t allowed to call me. ” She told me that she had never seen a student like her in her 30 years of working there” when I called her. I am still angry about this. But again my daughter is alive, but not necessarily supported at all by the App State community. It has been a very hard year and a half, because no one from that community is wondering where she is, how she is or when she is coming back. Ya’ll need to work on that.

Seth Stratton • Feb 3, 2015 at 1:46 pm

Excellent story Michael. It must be a difficult time in Boone right now and thank you for taking time to explain to the students, alumni and public those who are doing their best to help everyone process these losses of our Mountaineer family.