After more than a decade of studying numerous fossils with a focus on the Late Triassic Period, an Appalachian State University professor was recently involved in the identification and naming of a previously unknown species of the crocodile family.

Jordan Kimbrell | The Appalachian

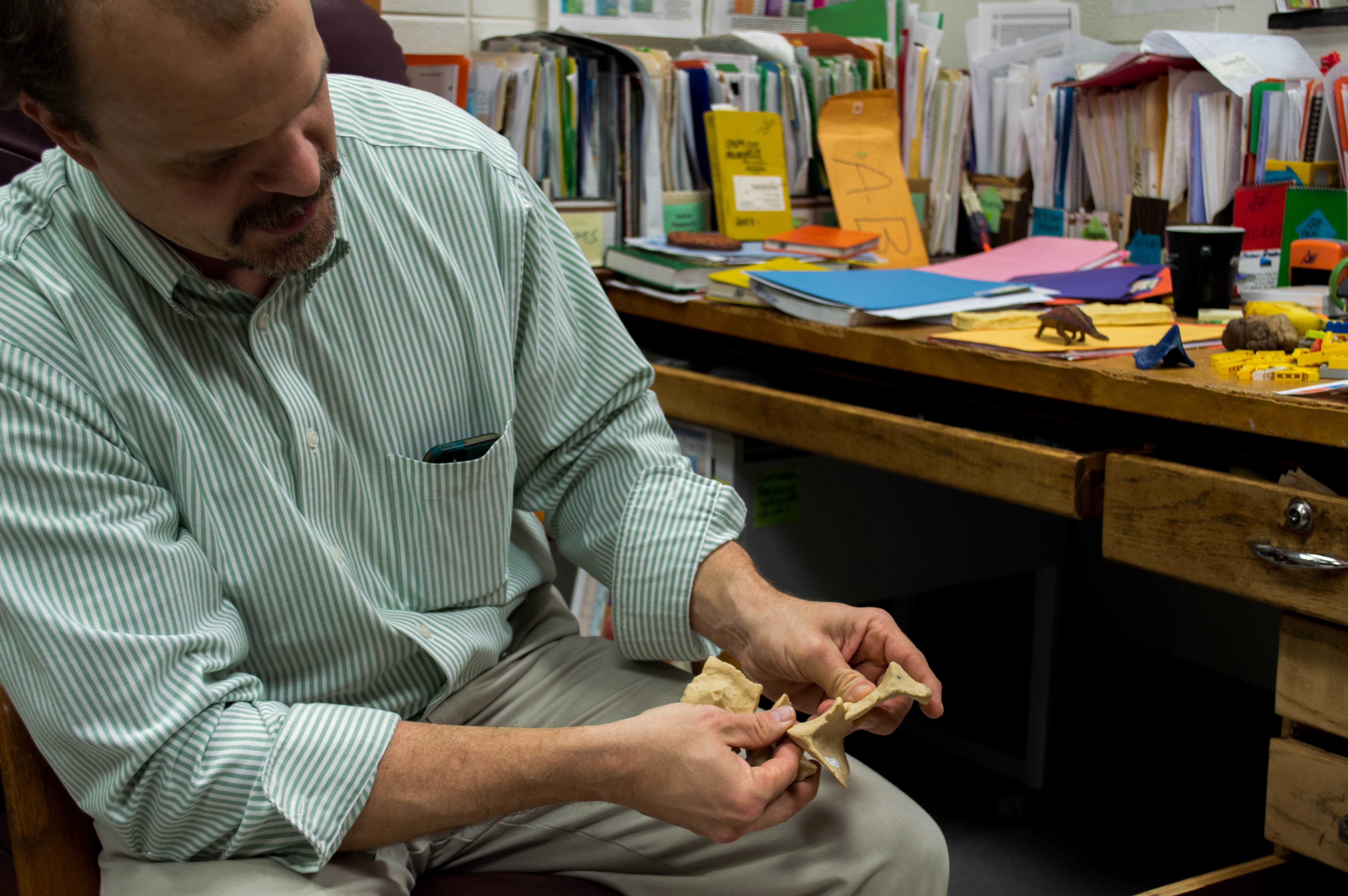

Andrew Heckert, a vertebrate paleontologist and professor in the Department of Geology helped to identify a new genus and species of the aetosaur. Heckert led an article published Jan. 24 in “The Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology,” where he described his discovery of the new species and made its name official.

Aetosaurs are primitive reptiles related to crocodiles and are thought to be herbivores that roamed the earth on the supercontinent Pangea when North Carolina was farther south and the climate was much warmer, Heckert said.

Aetosaurs are not very common – fewer than 10 aetosaur fossils have been found in North Carolina, with the one Heckert identified being one of the best in terms of its condition.

Heckert said the new genus and species he helped to identify must have been about 4-5 feet in length and is unique because of a band of armor plates around its neck.

“Crocodiles also have plates like these, but this aetosaur happens to be very spiny, and so presumably this was used as a defense mechanism,” Heckert said.

With the help of staff members and volunteers from the North Carolina Museum of Natural Sciences and an expert from Scotland, the new genus and species of the aetosaur was named Gorgetosuchus pekinensis.

Heckert said the dinosaur’s name means “neck-ringed crocodile.” Gorgetosuchus comes from the French world “gorget,” the metal neck ring that medieval knights wore for protection, and the ancient greek word “suchus,” meaning crocodile. Pekinenis refers to the Upper Pekin Formation that runs through today’s central part of North Carolina where the fossils were found.

“They are not real famous and no one gets famous by working on these aetosaurs, because they’re not on dinosaur terrain,” Heckert said.

The fossils were discovered in 2004, but preparing the rock to be broken into in order to take out the fossils took about a year. It then took about two to three months to get the fossils out. A total of 19 plates were found jumbled up in Triassic rock in Raleigh, which had been removed from a mining operation to access mud used in brick-making. Heckert said the plates date back to about 230 million years ago.

“What a lot of people don’t appreciate about fossils is that a lot of times, they come all jumbled and broken and so, it takes a lot of effort for somebody to take this away and show what the different pieces are,” he said.

Beginning in 2012, Heckert traveled to Raleigh once or twice a year to work on the fossils.

Heckert also sought out the help of Devin Hoffman, junior Appalachian geology major, to scan and make the necessary models of the plates that were found to allow other researchers to see the distinct features of this particular aetosaur.

Hoffman said they used two techniques to make the molds and casts. One technique was to use 3D scans, which took about 12 hours to make and then about another 12 hours to print. The second technique to make the casts out of silicone rubber involved pouring polyurethane resin into a mold.

Vincent Schneider, curator of paleontology at the North Carolina Museum of Natural Sciences and one of the co-authors of Heckert’s article, said molds were used to produce about five or six copies of the plates that went around the neck and they will be sent out to other institutions, so that they have copies of this new specimen.

Heckert said casts of the fossils of Gorgetosuchus pekinensis will go on display in the Triassic exhibit soon. The actual fossils will remain at the North Carolina Museum of Natural Sciences.

“All fossils that are scientifically studied have to end up in some sort of museum where you can be confident that they will still be there 100 years from now,” Heckert said. “Even though I am a paleontologist, I have essentially no fossil collection, because all the fossils that I’ve studied are at museums.”

Personally, Heckert said he is not planning on doing any additional research on the fossils soon. Instead, he has begun working on another specimen of a different animal.

“Part of what makes science replicable is that if other researches now find something similar to [Gorgetosuchus pekinensis], they will refer to my article or travel to Raleigh to look at the fossils for comparison.”

STORY: Chamian Cruz, Intern News Reporter