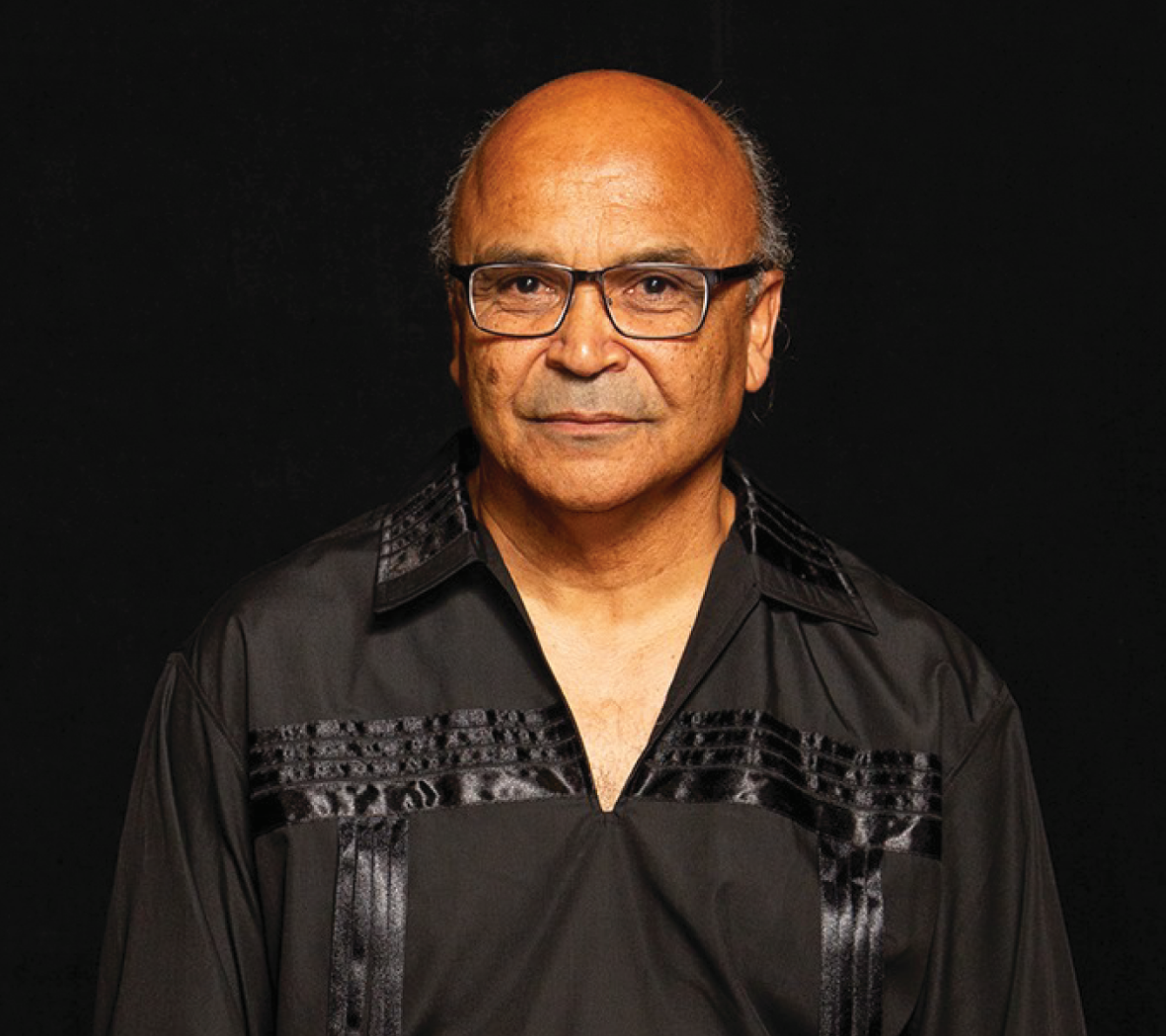

Over 50 students and faculty packed into a conference room in Plemmons Student Union on Friday. Every chair was filled and those without a seat sat on the floor. The crowd was there to see David Wilkins, a distinguished professor at the University of Richmond and scholar of American Indian law, governance and politics.

Wilkins’ talk, “Apart & Akin,” focused on the comparative historical and legal experiences of Indigenous peoples and African Americans in the South. While completing his master’s at the University of Arizona in 1982, Wilkins studied under Vine Deloria Jr., a well-known intellectual and activist for American Indian sovereignty.

A citizen of the Lumbee Tribe of North Carolina, Wilkins spent his youth in tri-racially segregated Robeson County, the heart of Lumbee tribal territory. Informed by his experiences and scholarship, Wilkins examined “our inherited cultural infrastructure” such as race, politics and law.

“Relationships between Anglo-Americans, African Americans and Native peoples have dominated social, economic and cultural dynamics,” Wilkins said. “These relationships have been defined frequently by violence and they are uneasy at the best of times.”

Wilkins framed how the Constitution views tribal nations and African Americans, each possessing a unique constitutional status. Although neither Native Americans or African Americans were legally recognized as human, tribal nations were recognized as political entities, he said.

“Were African Americans and Indigenous peoples entitled to human rights protections like whites?” Wilkins said, quoting Deloria’s book “Custer Died For Your Sins.” “Or were they lesser beings meant to exist in a perpetual state of inferiority because of their alleged beast-like nature with African Americans being perceived and treated as draft animals, while Natives were viewed as wild animals?”

In 1865, African Americans were granted personhood under the law, yet it wasn’t until 1879 that Native Americans were legally recognized as people, Wilkins said. Through the 20th century, both groups experienced similar systemic oppression, particularly around the ongoing issue of voting rights.

Yet, Wilkins said because Native peoples largely exist within sovereign nations, the Constitution does not protect Native rights in the same way as other U.S. citizens.

“I’m a citizen of the Lumbee Nation first, but I also happen to be a citizen of Virginia and I have national citizenship rights,” Wilkins said. “We have three layers of we should be the most protected class of citizens in the country, and yet, because of our Native citizenship, our rights can be abused in ways that other groups don’t have to fret about.”

Tribal nations are in a unique political position, Wilkins said, leading to ongoing battles between tribal governments and the federal government over land, sovereignty, recognition and trusteeship.

Wilkins said the U.S. has a “protectorate obligation to support Indigenous peoples, legally, culturally, economically and politically,” yet that responsibility is seldom fulfilled.