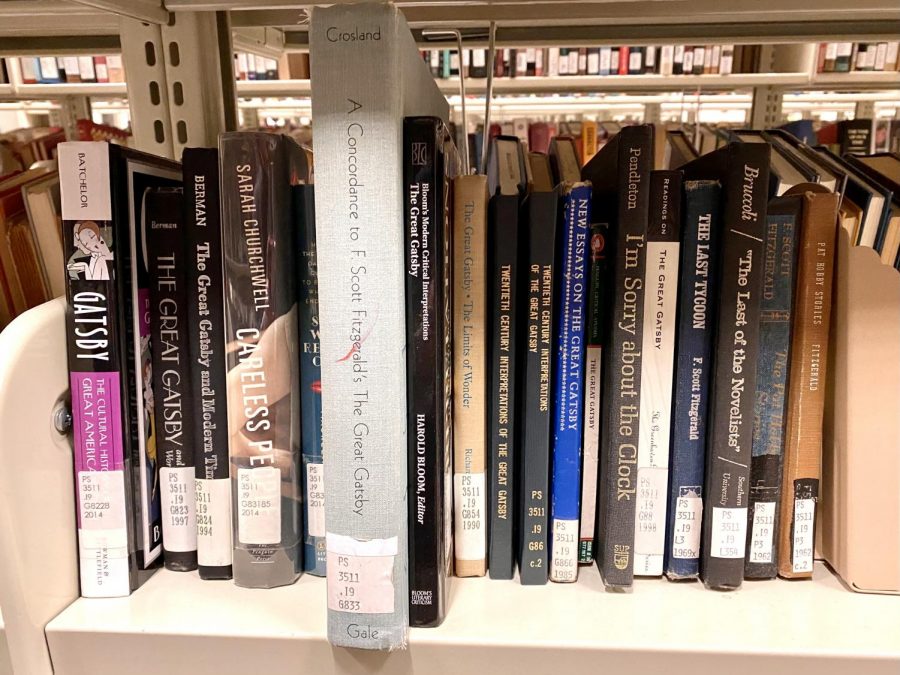

Reading research: Visiting professor explores the paths of classic novels

Books on “The Great Gatsby” at Belk Library. “The Great Gatsby” is one of the American classics that visiting assistant professor Anne Muenchrath is researching.

March 4, 2021

Before World War II, “The Great Gatsby” had fallen out of print. However, during WWII, the novel’s fate was forever changed by the Armed Services Editions. These were free pocket-sized paperback books sent to U.S. soldiers during the war to encourage them to read more. The ASEs circulated world literature, and one of the novels it popularized was “The Great Gatsby.”

Anna Muenchrath, current visiting assistant professor in the Department of English at App State, believes that if the Council on Books in Wartime, which was the committee that decided which books were selected to be ASEs, hadn’t chosen to include “The Great Gatsby” in its circulation, the book might not be the popular novel that it is today.

Muenchrath is studying how novels such as “The Great Gatsby” have become popularized due to choices made by people.

Muenchrath began her research project as a graduate student at the University of Wisconsin-Madison in 2016. She wanted to think about how choice has and continues to affect the circulation of world literature across the globe. She has taken what she calls “bite-sized pieces,” focusing on different situations where people’s choices impacted world literature circulation.

“I started thinking about, ‘well, what if we don’t only think about what world literature is, but we think about why it exists, like why do we read things from other places?’” Muenchrath said.

Soon after the ASEs were sent out, the Council on Books in Wartime started to get letters from soldiers, requesting that certain books they liked be included in the circulation, or even for their own books.

“There was a guy who wrote to the ASEs saying that he would like to be published in the ASEs, that he would like to write an autobiography of his experiences,” Muenchrath said. “He’s lying in a foxhole, and he’s writing this on a paper bag saying that he would like to write his story and be included.”

The ASEs were even able to circulate books that the U.S. had censored.

“One of those (books) is called “Strange Fruit,” which is a really interesting one because it’s about an interracial romance, which I guess is why it was deemed to be ‘too lewd’ for the population in the U.S., but the soldiers apparently loved it,” Muenchrath said.

Instantly a bestseller upon publication in 1944, “Strange Fruit” was popularized thanks to the ASEs.

“It’s all these little stories about how the circulation of these books affected people that I’m just riveted by,” Muenchrath said.

Presently, Muenchrath plans on bringing her research to the present, studying what choices are being made when circulating world literature today. For example, she will be studying Oprah’s book club, which circulates world literature by introducing novels from around the globe to an American public, much like the ASEs did.

Shabrina McPherson, who took Muenchrath’s “World literature Since 1650” class in the fall, said that Muenchrath’s enthusiasm “rubs off” on her students. McPherson said Muenchrath connects old texts to the modern day in the classroom, much like Muenchrath connects her research from World War II to today as she studies Oprah’s Book Club.

“It was really cool that she took something that was so much older and showed how relative it is even today,” McPherson said.

Whereas McPherson appreciated how Muenchrath connected texts throughout time, Ariana Fuentes Negron, who also took Muenchrath’s World Literature class in the fall, said she appreciated how Muenchrath connected texts throughout space and across different cultures.

“I had this understanding that the stories (from around the world) would somewhat all kind of sound and be the same, but just after taking her class, I realized that the world is so much broader than we like to make it,” Fuentes Negron said.