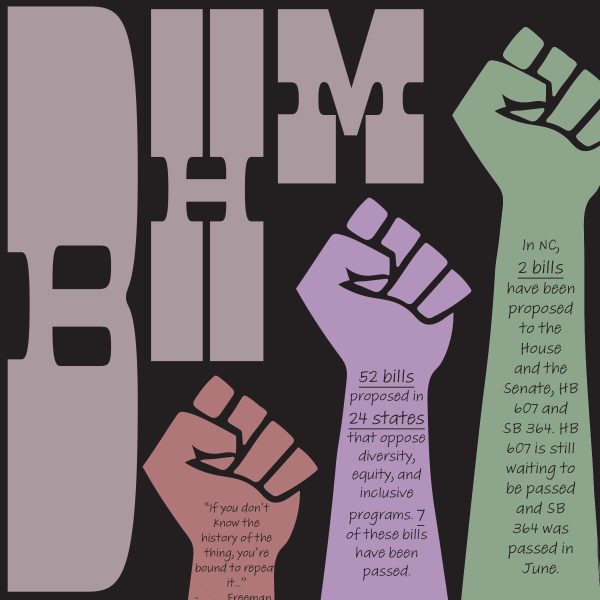

As of Feb. 9, there have been 65 bills introduced in 25 states opposing diversity, equity and inclusion programs, according to The Chronicle of Higher Education.

Of the 65 bills, 22 have been tabled or vetoed and eight have been passed into law.

With increasing legislation being introduced against diversity, equity and inclusion programs nationwide, some App State faculty and staff members said they have concerns about education on racial literacy and relations within college campuses and the greater community.

Leslie McKesson, an adjunct instructor in the Department of Interdisciplinary Studies, said she feels legislation against DEI programs will tighten the vice grip placed on K-12 teachers by state legislators and has begun to interfere with higher education curriculum.

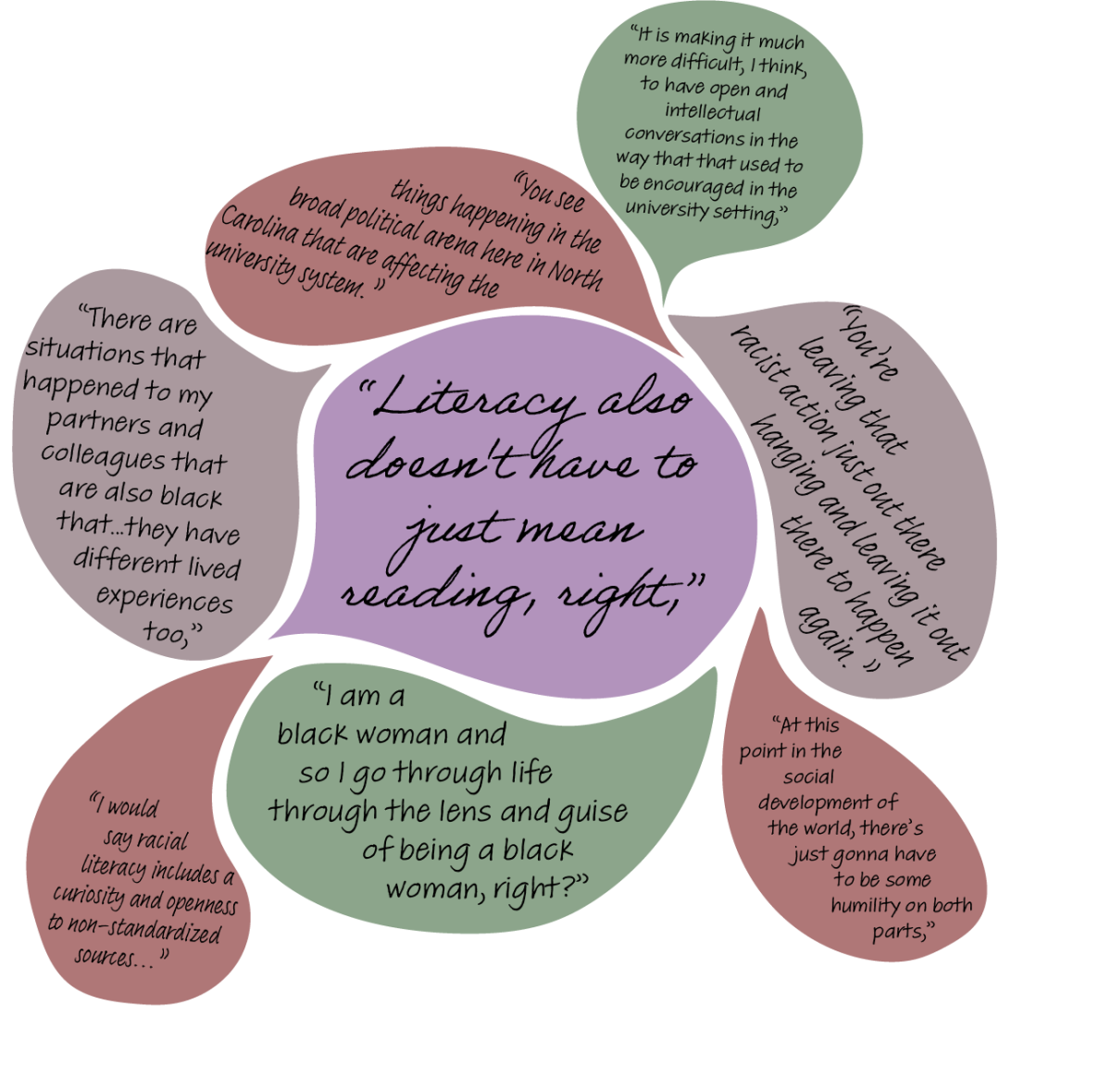

“You know, we’ve seen in states like Florida where there are actual pieces of legislation that are governing what’s taught in some of the higher education institutions,” McKesson said. “You see things happening in the broad political arena here in North Carolina that are affecting the university system.”

In North Carolina, two bills have been introduced in the House and the Senate, HB 607 and SB 364, according to the North Carolina General Assembly website.

These bills restrict state agencies, including departments and facilities, the UNC System and the North Carolina Community College system, from holding conversations about political, social and ideological beliefs with applicants or employees. HB 607 is still awaiting action and SB 364 was passed in June.

“It is making it much more difficult, I think, to have open and intellectual conversations in the way that that used to be encouraged in the university setting, you know,” McKesson said.

Dramaine Freeman, a doctoral student advisor in the Department of Leadership and Educational Studies, said Black history education is an important tool to employ in the learning environment so students understand the context of the society they live in.

“If you don’t know the history of the thing, you’re bound to repeat it because you want to be able to discern when certain political moves have been made that’s going to put you back in the same position,” Freeman said.

A concern Freeman said he has about recent legislation against DEI in education is the potential for increased limitations on resources for students to learn about Black history and cultures. In the K-12 public schools he has observed, he said he noticed a lack of access to Black history educational material for students. In some cases, the school’s library was their only source for this kind of material.

“We have to figure out a way to engage our youth, engage our communities, in a way that gets in front of them faster,” Freeman said.

For McKesson, racial literacy is defined not only by the education of history, culture and identities of races and ethnicities but by the approach taken to this education by someone who is not that race or ethnicity.

“I would say racial literacy includes a curiosity and openness to non-standardized sources, a willingness to critically examine what you thought you knew and a willingness to explore things that may be uncomfortable,” McKesson said.

McKesson holds Doctor of Education degrees in adult education and educational leadership and is a commissioner for the North Carolina African American Heritage Commission. She has also published a historical nonfiction book following the story of her great-great-grandparents titled, “Black and White: The Story of Harriet Harshaw and ‘Squire’ James Alfred Dula.” In November, McKesson won the President’s Award and Historian of Excellence Award from the North Carolina Society of Historians.

Ashley Carpenter, an assistant professor in the Reich College of Education, holds a similar definition and said racial literacy depends on access to and the use of educational resources and the ability to process the information being given.

Carpenter said a strong understanding of race relations and education on racial literacy is important to understanding the institutions of society because “race impacts class, race impacts gender, race impacts sexuality — all those things.”

Carpenter and McKesson said they feel racial literacy has no finite goal or endpoint, saying people build their literacy continuously throughout their lives as they take in new information and perspectives.

Higher education provides opportunities for conversations about Black history, culture and the way systemic institutions in the U.S. may affect the lives or have affected the lives of Black citizens, Carpenter said.

Because people tend to grow up in homogenous communities with people who look and sound like them, Carpenter said, higher education can serve as a forum of identities that students may have yet to be introduced to in their early years.

“Higher education not only allows for us to learn about those different viewpoints, but it also provides us a space to have some of these conversations,” Carpenter said.

Carpenter is currently teaching Diversity in Higher Education, a course offered on demand at App State. She said the class often partakes in conversations about race relations in the U.S. She initiates the conversation by encouraging students to think about their individual identities and how it affects their perception.

“I am a Black woman and so I go through life through the lens and guise of being a Black woman, right? But, you know, there are situations that happened to my partners and colleagues that are also Black that I don’t necessarily fully — I don’t want to say I fully don’t understand — but they have different lived experiences too,” Carpenter said.

After focusing on individual perspectives, Carpenter said it is easier to shift the conversation toward the general experience of people who share identity traits without stereotyping or tokenizing.

However, Carpenter said, many variables must be considered for these conversations to be productive for all participants, especially at a PWI. When conversing about the Black experience in the U.S., things like tokenism, microaggressions and racism can make the conversation an unsafe forum for students of color, Carpenter said.

Additionally, conversations about Black history and systemic racism may place Black students, involuntarily, into a position of guidance and expertise for white students, McKesson said.

“I’ve had people that actually have told me, in the context of conversations about race, ‘Well, we don’t know what to do. So you’re gonna have to tell us what to do,’” McKesson said. “And that literally takes a second burden, a second bag of bricks, and places it on already broken shoulders.”

One idea McKesson suggested to help conversations about race at a PWI be effective and respectful is for instructors to set guidelines for the conversation. This may look like addressing the students of color in the room to ensure they do not feel they are being looked at “under a microscope” and they “do not have to provide all the answers,” McKesson said.

Another guideline McKesson said could be installed before a conversation about race is that racism, intentional or unintentional, should and will be called out during the discussion. This duty will most likely fall to the instructor or professor, McKesson said.

McKesson said this guideline is an important piece during conversations about race because if racism is not addressed, “you’re leaving that racist action just out there hanging and leaving it out there to happen again.”

However, McKesson said the way addressing racist comments happens during these discussions is important.

“At this point in the social development of the world, there’s just gonna have to be some humility on both parts,” McKesson said. “I mean there needs to be humility on the part of the white person who says, ‘Well, I didn’t intend that to be racist it wasn’t, you misinterpreted.’ But there also needs to be some humility on the part of the person who heard that comment to say — you know to share — why it was perceived by them as a racist comment.”

McKesson said to place education at the forefront of the conversation and let the conversation lead towards understanding rather than defensiveness, if possible.

McKesson said another key element in learning about Black history and increasing one’s understanding of race relations in the U.S., particularly in regard to Black citizens, is to read work written and produced by Black people.

McKesson suggested those interested in learning more could read books such as “How to Be an Antiracist” by Ibram Kendi, “The 1619 Project” by Nikole Hannah-Jones and “The Hemingses of Monticello” by Annette Gordon-Reed.

McKesson said some good authors to read to build knowledge on Black history and Black-white race relations in the U.S. are Lerone Bennett Jr., John Hope Franklin and Henry Louis Gates Jr.

Carpenter said a majority of her initial learning during her Ph.D. program came from reading work by bell hooks.

Carpenter suggests those interested in broadening their education read “Why Are All the Black Kids Sitting Together in the Cafeteria” by Beverly Tatum; “White Fragility” by Robin DiAngelo; “The New Jim Crow” by Michelle Alexander; “Americanah” by Chimamanda Adichie and “The Racism of People Who Love You” by Samira Mehta.

“Literacy also doesn’t have to just mean reading, right,” Carpenter said. “So it can mean listening to a really awesome podcast, it can be going to someone’s really great lecture and it can be watching a TV show that gave you a different perspective about race.”

Freeman said one of his favorite resources for Black history education is a website titled “Black History in Two Minutes (Or So),” created by Robert Smith. Freeman said he likes this resource because it contains information is about lesser-known historical Black figures and events.

McKesson also said Black history education can happen outside of readings and classroom exchanges and the beneficiary quality of resources like museums and historical sites should not be undervalued.

McKesson suggested visiting the National Museum of African American History and Culture in Washington, D.C. and the International African American Museum in Charleston, South Carolina.

“Of course now there’s travel, but a lot of museums have an online presence and have some amazing programming that can be completed online,” McKesson said.

She said those interested should look into resources available in North Carolina, such as the North Carolina African American Heritage Commission. McKesson said the commission has completed and is working on creating projects like Freedom Roads which creates a state-wide trail of landmarks of historically significant sites in Black history in North Carolina.