Authors offer new perspectives as Boone turns 150

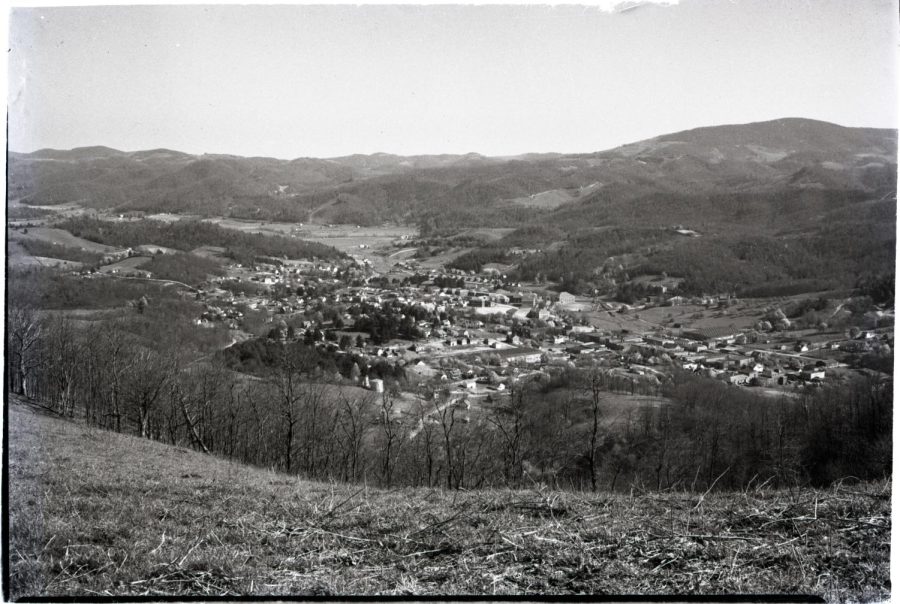

View of Boone from Rich Mountain #6 Photograph by Palmer Blair, Photo Courtesy of Watauga Digital Archives.

September 16, 2022

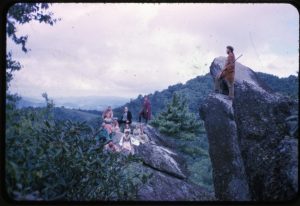

Boone celebrates its 150th anniversary this year. To commemorate this milestone, the Town of Boone has planned many events throughout 2022 recognizing Boone’s uniqueness in the last 150 years, including a summer concert series at the Jones House, nightly summer performances at Horn in the West and “Boone Reads Together;” a reading program focusing on a celebration of local history and the stories of Boone.

Throughout the year, the program has featured numerous local authors, with books focusing on topics from archeological records, local personal experiences and the town’s evolution from unincorporated community to university town.

In 2020, former professor of anthropology, Thomas Whyte, wrote “Boone Before Boone: The Archaeological Record of Northwestern North Carolina Through 1769.” The book was inspired by the lack of definitive literature on the topic. Whyte said he sought to put “gray literature, technical reports and various articles in professional journals” into “a package that the non-professional archaeologists could enjoy.” Whyte describes “tourism” as the theme of his book.

“The first people that came to this region visited about 12,000 years ago at the end of the Ice Age, Native Americans, they were migratory hunters and gatherers,” Whyte said. “They were not sedentary. They did not live in villages. They did not have crops. They did not have permanent structures.”

It wasn’t until between 900 and 1100 A.D. when slightly increased temperatures caused Piedmont dwelling natives to migrate up into the High Country, Whyte said. After this, another small ice age occurred, leaving Boone and northwestern North Carolina without permanent settlements until European colonization, Whyte said.

Just as early Native Americans visited the region during warmer seasons, Whyte suggests human activity since then has mimicked their behavior.

“After about 1400 A.D., all the way up until Europeans arrived in Daniel Boone and Bishop Spangenberg. There was nobody here permanently only, again, people visiting seasonally. So it’s a story about tourism,” Whyte said. “And that rings a real bell with Floridians and the Georgians and the South Carolinians who come up here during the summer.”

Earlier this year, the university announced a land acknowledgement statement which moved to recognize the original inhabitants of the Boone area.

“Appalachian State University acknowledges the Indigenous peoples who are the original inhabitants of the lands on which our campus is located. The Cherokee, Catawba and other Indigenous peoples left their mark as hunters, healers, traders, travelers, farmers and villagers long before the university was established,” the statement said.

The statement also included an acknowledgement that many Indigenous descendents continue to live in this region, which is “an area with settler-colonial policies including those that attempt to disenfranchise, remove and eradicate Indigenous people and their way of life.”

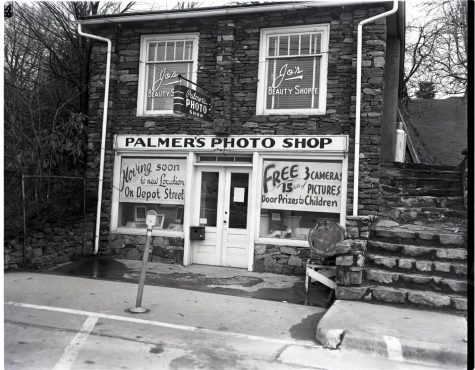

Eric Plaag, author and local historian, catalogs the post-colonial period and those following it in his book “Images of America: Remembering Boone.” The book, featuring photos from the Digital Watauga archives, is separated into six chapters chronologically cataloging a visual history of Boone and is “intended to be a part of the celebration of the 150th anniversary of Boone’s official incorporation,” according to the introduction of the book.

While primarily recording the growth of the town through means of image, Plaag’s inclusion of a photo collection by Palmer Blair, a 1950’s freelance photographer for local newspapers, aims to bring focus to those who may not traditionally get the spotlight.

“The vast majority of people included in that chapter are regular folk,” Plaag said. “They were just the guy that worked at the supermarket. They were just the guy that washed dishes at the restaurant, you know?”

Plaag said finding those who were in the images was a process rooted in the Digital Watauga Project, where the organization would upload photos to Facebook and ask locals to identify individuals.

“We actually posted all 400 images on Facebook over a series of weeks, 50 at a time, and asked the Digital Watauga community: ‘Tell us who this is,’” Plaag said.

By the end of it, nearly two-thirds of the individuals were identified.

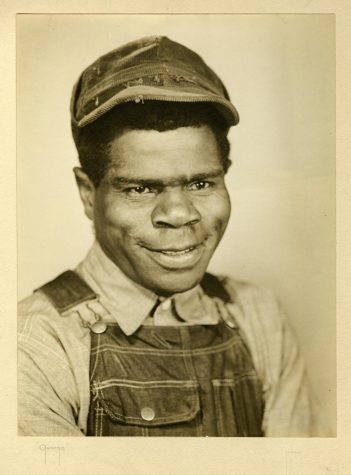

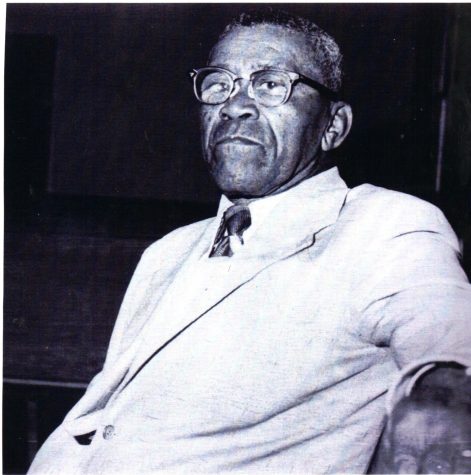

“I think those stories are important,” Plaag said. “I particularly think that stories like George Horton’s are important because they speak to not only the ways in which a community interacted with people who were marginalized for a variety of reasons, but also the consequences that come from that marginalization.”

George Horton, a Boone resident in the mid 20th century, was included in the book’s photos. Horton, though renowned for his kindness, struggled with poverty, alcoholism, legal challenges and homelessness, Plaag wrote.

During one of the instances when Horton found himself in jail, Horton slammed a steel jail door on a jailer’s hand, severing at least one of the jailer’s fingers and causing more jail time, Plaag said.

“It raises a question of ‘Why was that his reaction to what was happening?’ ‘What specifically was happening?’,” Plaag said. “We don’t know. We have a newspaper account that comes from the jail and not from Mr. Horton. Was he exercising poor judgment? There’s not a good way to know.”

Horton died during a snowstorm in 1973, Plaag said.

“In any case, as familiar as a person as he was, he ends up dying in the snow,” Plaag said. “Because there was nowhere for him to live. No one would give him a place to live. No one would help him in the community. That’s an important story to tell.”

As housing remains an issue for Boone residents, Plaag found the book demonstrates both past and present needs of the region.

“We have a really pronounced issue of a large number of people experiencing homelessness in our community,” Plaag said. “It is exacerbated by the fact that several close friends and colleagues of mine, or people who work in Boone, cannot afford to live with their families. That’s a problem.”

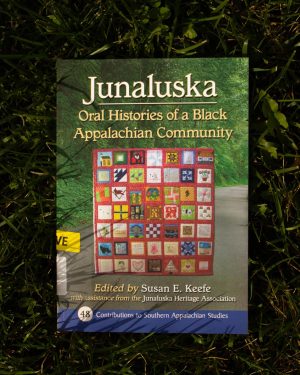

Another book selected for “Boone Reads Together” was also selected as a part of the 2022-23 App State Common Reading program.

“Junaluska: Oral Histories of a Black Appalachian Community,” focuses on the history of the Junaluska community. Junaluska is one of the earliest Black communities in western North Carolina region, according to the Junaluska Historical Association website.

Susan Keefe, professor emerita of anthropology and co-editor of the book, has spent decades working alongside the Junaluska community to increase awareness of their existence in Boone.

In 2011, St. Luke’s Episcopal Church took on an effort to meet with members of the Junaluska community who attended the Mennonite Brethren Church. Their intention is to do their part in offering reparations for slavery, Keefe said.

Through these meetings, the Junaluska community and its importance to Boone was highlighted and recognition grew. During this time, the need for a written narrative of Junaluska became more apparent.

During interviews with members of the Junaluska community, the book “Junaluska: Oral Histories of a Black Appalachian Community” came into view. Helping piece together a narrative from community members was “incredible,” Keefe said.

The community was often described as “The Hill” or “The Mountain” depending on how high up you lived, according to a report taken from a 1973 interview with community member Reverend Ronda Horton.

After the Civil War, segregation took full force in the High Country and divided every way of life with separate schoolhouses, bathrooms and stores. Finished in 1898, and built in the heart of Junaluska, many members of the African American community saw the Boone United Methodist Church as the only place of refuge, according to a 1997 paper written by Keefe.

Through the church’s influence, the Junaluska community was able to come into community with one another. In 1918, the Boone Mennonite Brethren Church was built which also operated as a center for the Junaluska community to thrive throughout the 1930s, ‘40s and ‘50s.

During editorial meetings in the Mennonite Brethren Church’s fellowship hall, Keefe saw the Junaluska people take control of their narrative.

“They eliminated a few things, they corrected a few things so that the final arbiters of what was put into the book was the Junaluska community itself,” Keefe said.

Through the impact of the book, Keefe said, the university, in partnership with the Junaluska community, will be able to move onto their next project; naming previously unmarked graves in the segregated Black cemetery near campus in October.

“The cemetery has been resurveyed through ground penetrating radar to detect anomalies throughout the underneath surface of the ground and have been able to determine there are 165 graves in that cemetery, most of which are unmarked,” Keefe said.

This has been a particular point of interest for the Junaluska community, Keefe said. Members of the community have also sought improvements in the Boone City Cemetery and the Clarissa Hill Cemetery, which has been where their dead have been buried since the mid 1950s.

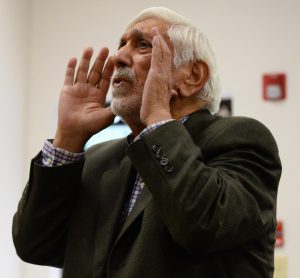

Community member and representative of the Junaluska Heritage Association, Roberta Jackson, said she is “very excited” about the work being done with the respective cemeteries.

“A few years ago, ASU gave us our first $1,000 to build a monument recognizing the unmarked graves in the city cemetery,” Jackson said.

Jackson said the university has provided an immense amount of help toward the many projects they have wanted to work on, including the cemetery project.

“It’s cooperation, organization and working together that really makes these things happen,” Jackson said.

Keefe and Jackson are also looking forward to their book being selected as the university’s common reading for the academic year.

“No one in Boone knew about Junaluska when we were first founded in 2011, but because we had done so much to make the Town of Boone what it is today, we felt we needed to be recognized, and the book helped us get there,” Jackson said.

Jackson said she appreciates how the book has connected her with other members of the Junaluska community such as her neighbors Joseph Grimes and Carolyn Grimes. The kinship created in the Junaluska community is something Jackson said she wishes could be more widespread in Boone. She said she believes that kind of relationship between community members is a lesson for all of Boone.

“We’re all the same people, even if we don’t know each other or what’s going on in our families,” Jackson said. “We are all people trying to make it and learning to live and love each other.”