Jailhouse turned southern bistro: A history of Proper

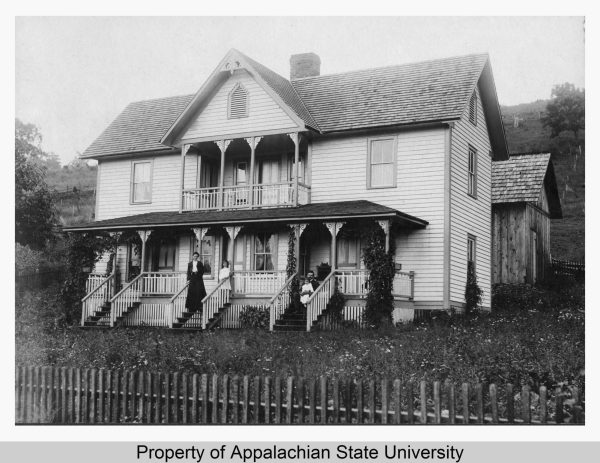

The Old Watauga County Jail circa winter 1990. The jail was being used as a private residence at the time. Image courtesy of the Downtown Boone Development Association Collection, Digital Watauga Project.

September 14, 2022

A jailhouse marred with tally marks, a fraternity house to college students and Proper, a Southern bistro with an “Eat More Collards” slogan. These facilities occupied the property of 142 Water St. which Boone’s Town Historic Preservation Commission is considering for Historical Landmark status.

Eric Plaag, a historical consultant, wrote in the Downtown Boone Historic Resources Survey Report that the property was built in 1889. Following its construction, the building became a jail, a fraternity house in the late 1900s and Proper in 2010.

The structure of the jailhouse allowed the jailer and his family to live within the jail. The prisoners were housed on the first and second floors with development costing $5,000.

It was the fourth jail in Watauga County and is the only surviving 19th century government building in the county, according to Plaag’s report. Plaag said he speaks as a historian, not on behalf of any organization.

“It’s the last best example we have of that type of architecture,” Plaag said. “There’s nothing quite so valuable as being able to see the architecture in person, analyze it closely, talk about it, show things to other people about workmanship and materials, etcetera that go into those things.”

The jailhouse was modeled after a “Folk-Victorian” style to fit the industrial needs of the structure. Plaag defines Folk-Victorian facilities as a subset of the English Victorian “Queen Anne” style, with “T” shaped projects.

Home Reference, a home improvement website, notes Folk Victorian structures imitated expensive architectural styles to make luxury accessible to the working class.

“Stunted brackets are centered on the pilasters, while a pair of elongated brackets frame each window opening on the second floor,” Plaag wrote for the Downtown Boone Historic Resources Survey report. “A second, alternating corbel line separates the first and second floors but is mostly obscured by the front porch. The roof is clad in small, metal shingles that may be original to the house.”

The original brick measured 18 inches to deter escapes, comparable to an average thickness of a modern U.S. brick size of 3 5/8 inches according to First in Architecture, an online guidebook for architecture. Plaag said bricks couldn’t be imported to the High Country due to accessibility and road conditions, so clay was kiln near or on the property to make bricks.

“They did what every other person building a brick house had to do, which was find a good deposit of clay and then kiln the brick nearby or on-site on where you were building,” Plaag said. “Watauga County soil does not lend itself to high-quality clay for brick building. So what you end up with are awful bricks.”

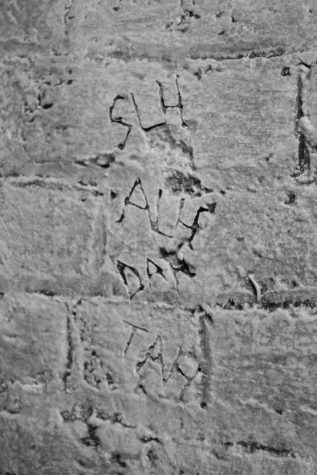

Wooden floors in the first floor cells were reinforced with concrete, interfering with plans to tunnel out from the ground. Markings discovered on the walls in one of the old cells belonged to previous prisoners.

“Prisoners were given penance, usually to God,” said Trent Margrif, a former member of the Cultural Resources Advisory Board and lecturer at App State. “If you look at a history of criminal justice and how we got there, yes, your terms would be reduced if you asked for a higher power to intervene.”

Decommissioned in 1927, the old jailhouse was transformed into residential housing after the inmates transferred to a new establishment built behind the Watauga County Courthouse.

Plaag attributes the closing of the jailhouse to racial tensions in the 1920s. Plaag said white inmates were “alarmed that there was not a way to segregate prisoners.”

The county’s population grew with the expansion of the Appalachian State Teachers College in 1929. The property was subsequently transformed into residential housing.

“We got into a period in the mid to late 20th century where this house, or former jail, was adaptively reused to fill a need without much regard to preserving it,” Plaag said. “With most people at the time it was ‘here’s an old building, we can put some cheap apartments in there or house people cheaply’ this is not unusual. It’s a common part of stories in historic buildings.”

During its restoration, the building’s security elements such as deadbolts and cells were removed. An entry from TheClio, written by university history professor Kristen Baldwin Deathridge and former student Evan Wallace, said a root cellar, protected by a trap door in the floorboards, is the only characteristic of the building untouched during this time.

From 1925 to the 1980s, the jail housed university students. Plaag’s report mentions graffiti uncovered on-site revealed the work of former prisoners and college students.

“It’s disappointing to me that the owner chose to uncover the jail cell walls before it became a fraternity house because they thought the graffiti was neat and a cool thing to display,” Plaag said. “That’s just an invitation for everyone else to write their name on the wall and of course, you destroy the history by doing that.”

Other commercial buildings of early Watauga County evolved into residential units. Margrif, who also gives walking tours to his class, emphasizes the county’s development in his first-year seminars.

“Its primary use only lasted, it looks like, 30 to 40 years. So, in its lifetime, the building was used for far more different purposes,” Margrif said. “In my class, I do talk about adaptive reuse. It gets into how we build today. We’re looking for that next use.”

Margrif, who has written about prisons transformed into microbreweries, said he finds the history and premise of Proper “interesting.”

“The term ‘jail’ still is a little confusing to me, but I think that’s perfect because it’s a marketing angle,” Margrif said. “It’s a unique experience. It’s not fast food. It’s not mass-produced.”

Samuel Furgiuele, a town attorney in Boone, co-owns the property with his wife. Furgiuele convinced the previous owners, Don Dunlap and his son Monty Dunlap to sell the property instead of demolishing it.

Furgiuele said the fraternity caused some damage to the interior.

“There are Greek letters carved into the wall of the cell, where people used to keep track of their incarceration by putting hash marks for the days,” Furgiuele said.

Furgiuele never rented to fraternities and “didn’t have much luck with residential rentals.” With this, the Furgiueles opened the space for restaurants to rent, the first being The Old Jailhouse in 2005, which specialized in Indian cuisine. The restaurant maintained the fortified bricks used in Stephen’s original construction.

Angela Kelly, the current lessee of the property and owner of Proper, attended App State in the ‘90s and went to a party on the land while it was rented out to university students, describing the area as a “typical college boy house.”

Kelly, who has stayed in Boone since completing her undergraduate degree, worked in the restaurant industry before renting Proper from Furgiuele.

“It was in pretty bad shape,” Kelly said. “I think the building was going to be torn down and turned into a parking lot until the man who owns the building purchased it. It has such a historical significance for the town.”

Proper has offered locally sourced, Southern-style cuisine for almost 12 years. Kelly said Proper is a way to support herself and the wider community.

“It’s been important to us since day one to support as many of our local producers as possible,” Kelly said. “I’ve been with some local farmers here since I opened and it’s great to have that connection with the community where you’re just equally appreciative of each other’s efforts.”

Plaag said historical buildings are meant to be occupied in one sense or another. In his eyes, something must be of “astounding historical merit” to remain untouched.

“People, tourists, in particular, love the opportunity to be within spaces that are historic for some reason. Particularly if that building had a different purpose,” Plaag said. “That historical value brings value to the property itself. People still want to understand that history.”

As of August, Proper is still up for review for Local Historical Landmark Status and the National Register for Historic Places. Plaag wrote a Local Landmark Designation report for the Preservation Commission as a volunteer.

After revision and submission, the report awaits review at the North Carolina State Historic Preservation Office.