Visitors of Mystery Hill may recognize the white house located to the side of the property. What some might not know is that App State’s history is deeply connected to the over-a-century-old home, which has overcome great adversity over the years.

That white house is the Dougherty House, and was home to Blanford Barnard “B.B.” Dougherty, his brother Dauphin Disco “D.D.” Dougherty and D.D. Dougherty’s wife, Lillie Shull Dougherty. The three are credited as the founders of App State.

The trio found that rural Appalachia lacked the resources needed to foster education. With the help of their father Daniel Baker Dougherty and his monetary support, the three founded Watauga Academy in 1899. After advocating for an education bill that was eventually passed in Raleigh, they opened Appalachian Training School for teachers in 1903 as an official state institution, according to a previous undergraduate bulletin published by App State.

The school would undergo significant growth and later was turned into a two-year college, known as Appalachian State Normal School in 1925. Eventually, the college became a four-year institution in 1929, called Appalachian State Teachers College, before becoming Appalachian State University in 1967.

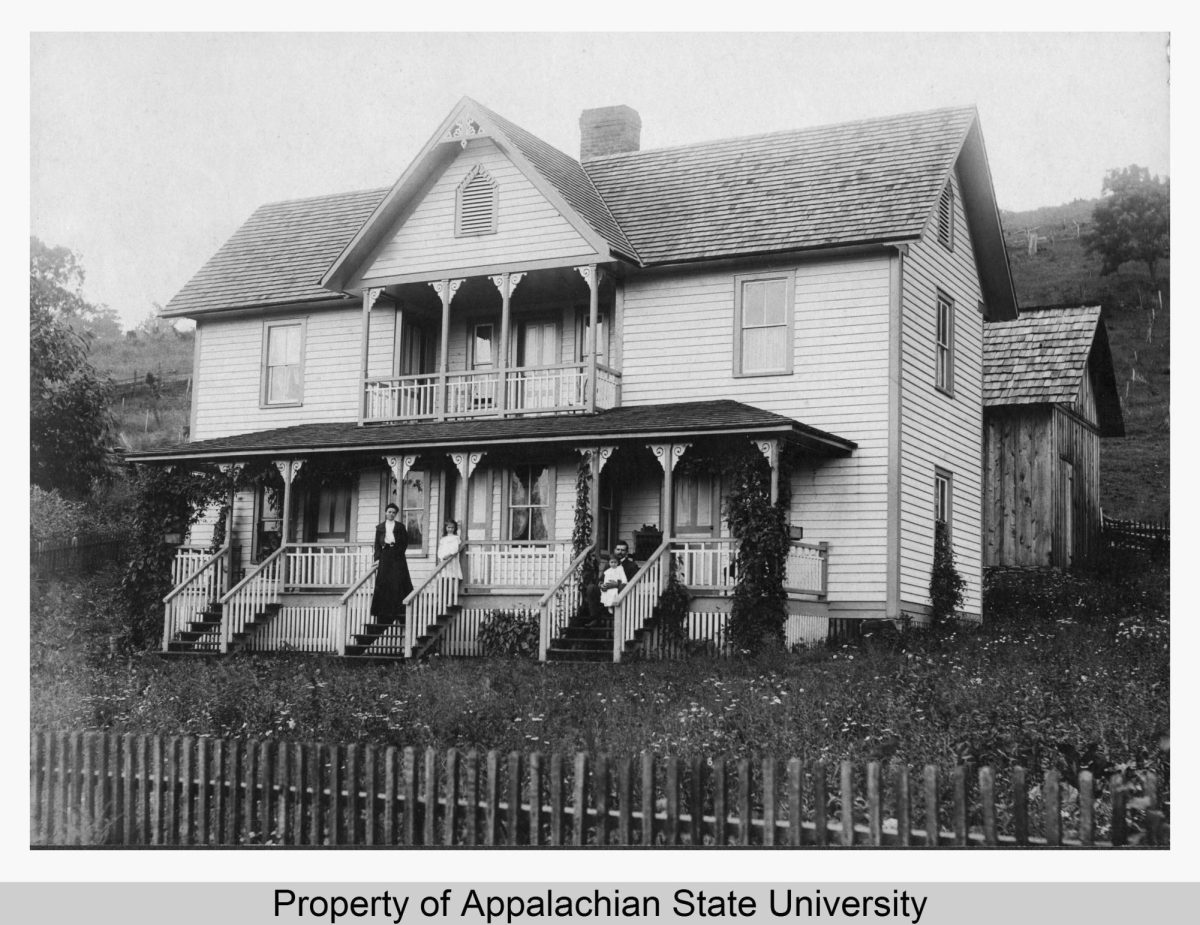

The historic home was constructed from 1902-03 and was originally located on Rivers Street on the lot where the Rivers Street Parking Deck now stands.

The two-story building models an I-house style which was common in the rural U.S. at the time and contains Queen Anne and Gothic Revival details its construction. It was built primarily out of pine lumber from the Dougherty family farm and was designed by D.D. and Lillie Shull Dougherty, according to a 1987 building survey project of the house.

Sitting on a plot of 28 acres, the land immediately surrounding the house was rich in vegetation native to the Appalachian region. Numerous large trees such as a Fraser magnolia, dogwoods, peach and pawpaw trees surrounded the home, according to the building survey.

Doris Stam, a relative of the Dougherty family and researcher of App State’s beginnings, wrote in her book titled “Mountain Educators” that a common misconception of the house is that it was where the trio founded Watauga Academy and hosted classes. According to Stam, Watauga Academy was founded before the house was built.

Stam’s research indicates that D.D. and Lillie Shull Dougherty previously lived in a house called Meadow View, which doubled as a boarding school until they moved out and started construction of the Dougherty House in 1902. Still, the house remained a central figure in the growth of App State.

As the educational institution grew, the house received various renovations. In 1915, the front porch was expanded. That same year, the house became the first in the area to be wired for electricity, which was provided by a large water-powered dam that also supplied electricity to the school. Three years later, the home would be one of the first in the area to receive indoor plumbing. In 1937, a partial basement was dug.

The original furniture in the home was sometimes lent out to newly constructed dorms located on the expanding campus. On more than one occasion, Lillie Shull Dougherty was known to allow her personal piano from her home to be moved to campus for music programs, according to the building survey.

As App State continued to grow, the house remained on Rivers Street and was home to descendants of the Dougherty family.

In 1983, Annie Dougherty Rufty, the last person to occupy the house and an heir of D.D. and Lillie Shull Dougherty, sold the historic house and surrounding acreage to App State for $1 million.

The home met the criteria to be classified as historical and therefore eligible to be preserved, but the full process to register it would not be carried out for several years.

On April 5, 1984, The Appalachian reported the Development Office at App State planned to restore the house and turn it into a faculty and alumni building. However, The Appalachian later reported in 1987 that App State’s renovation plans were put on hold when termites were discovered in the house.

By 1988, Chancellor John Thomas announced App State planned to move the house to a storage area to create parking space and build a math and science building. The Watauga Democrat reported that in response, Boone Town Council passed a resolution urging App State to preserve the house in its original location.

Despite protests from students and the town, some of which were covered by The Appalachian, it was announced that the house would be temporarily relocated to the State Farm Lot.

On June 1, 1988, the home was dislocated from its foundation, its roof sawed off to allow passage under stoplights and wires, and moved to its temporary location. News outlets across the state covered the event.

The once-regal home that housed the very foundation of App State would sit in the State Farm Lot for over a year, exposed to the conditions, its roofless top covered by a sheet of plywood and plastic wrapping, as reported by The Appalachian in 1989.

“We did what we could do to stabilize it. It’s on a foundation and weatherized,”

Thomas was quoted in a 1989 edition of The Appalachian. “But there’s nothing you can do to protect an old house.”

According to Stam’s research, the university planned to acquire burn permits for the home as time progressed.

Meanwhile, Wayne Underwood, who was then the owner of Mystery Hill, was recovering from the loss of approximately 150,000 artifacts after a fire destroyed a museum building. His son Matthew Underwood, current owner of Mystery Hill, said his father saw an opportunity to preserve the house and acquire new space for a museum.

“We woke up one morning to a news article that they had moved it,” Matthew Underwood said. “They were trying to get a permit to burn it and everybody said, ‘No, we’re going to stop that. You can’t burn this house.’”

After negotiations, which Matthew Underwood described as “back and forth,” Wayne Underwood formed a nonprofit, Appalachian Heritage Museum, and purchased the Dougherty House for $10 in the late summer of 1989. The museum is still the owner of the house.

He set aside the insurance money from the fire and donations to the nonprofit to move the house and start renovations. However, flooding from Hurricane Hugo made it impossible to move the house in September, and further contributed to the damage the house sustained from weather-related conditions.

Matthew Underwood described the process of moving the house to Mystery Hill as complicated. Still, in October of 1989, the house was on the move again — this time for a final destination.

“We closed 321 for about four hours because it was as wide as the entire road,” Matthew Underwood said.

The current owner of Mystery Hill said renovations cost a substantial amount, but eventually the house was restored and preserved to the best of the nonprofit’s abilities, resembling the way it looked back in 1903. It was reported that App State donated 10% of the funds needed to restore the house.

Today, visitors can tour the house at Mystery Hill and view the artifacts from the house. In the basement of the home is a museum with over 250,000 Native American artifacts. Even 100 years after the home’s initial construction and two relocations, the Dougherty House continues to educate people about Boone and App State’s history.

Sharon • Mar 19, 2024 at 4:26 pm

Great job enjoyed

Janie Winebarger Dougherty • Mar 19, 2024 at 10:09 am

I really enjoyed seeing this article about the Dougherty home. I appreciate the effort of research to get the details correct.

Many of the first students actually stayed in the home and often took a meal there. Lillie Shull Dougherty was a remarkable lady to keep that house (and cook). She worked non -stop at all the jobs that included. She was also a skilled teacher and physically beautiful.

I enjoyed reading a series story about her in the N.C. State Magazine, just last year, so well written by one of the family members.

Carolyn Hart • Mar 19, 2024 at 8:50 am

Well done!

Alan • Mar 8, 2024 at 9:32 am

Kudos to the author to do all the research putting together this article.

Ross Cooper • Mar 19, 2024 at 9:41 am

Ditto that! Thank you for this excellent feature, Madalyn Edwards.