Gourds, banjos, and djembe drums filled Rosen Concert Hall, creating a captivating display of cultures at “From West Africa to Appalachia: Expert Insights and Demos with Music and Dance” Feb. 15.

The musical gathering, hosted by High Country Humanities, offered a mixture of African and Appalachian cultural expressions and featured a tapestry of dances, songs, fashion and presentations from various App State professors to explain their historical contexts.

Darci Gardner, director of High Country Humanities, said this event is for the “campus and broader public to learn about the stories, histories and traditions of rural communities from our state and around the world.”

The event consisted of three interactive presentations followed by an audience Q&A.

First, Stephanie Mazan, an assistant professor in French and Francophone Studies described as a “proud daughter of Cameroon” on her website, helped attendees listen to and interpret the cultural context of both traditional and popular dance songs from Cameroon, a country in central Africa.

The event explored the cultural connection between Africa and Appalachia.

“When it comes to culture, we are all tied,” Mazan said.

The first song Mazan shared was “Soul Makossa,” the most sampled African track of all time according to Sample Chief, a collective dedicated to finding samples of African music in other artist’s songs. The track appears in songs such as Michael Jackson’s “Wanna Be Startin Somethin” and Rihanna’s “Don’t Stop the Music.”

Mazan also showed how colonialism influences cultures. At the event, she wore a popular dress among women in Cameroon called a kaba ngondo.

Mazan said the kaba ngondo came when missionaries arrived in Cameroon in the middle of the 19th century. They told Cameroonian women to cover up because the women walked around bare-chested. Cameroonians heard “coba,” not “cover,” because in the Duala alphabet, there is no “r” or “v.” This eventually led to the creation of the kaba, based on the misheard word coba.

According to The National Park Service, the start of African cultural contribution to Appalachia was involuntary.

“Beginning with a narrative of forced migration and slavery, the musical practices of African Americans have significantly contributed to the Southern Appalachian musical sound that is heard in the Great Smoky Mountains and surrounding areas,” reads The National Park Service website.

Next, Julie Shepherd-Powell and Trevor McKenzie spoke on the West African roots of Appalachian dance. Shepherd-Powell demonstrated flatfoot dancing, a kind of folk music tap dancing, and was accompanied by McKenzie playing the banjo.

She explained that there were indigenous, African, and Irish influences in flatfooting. She said there was a lot of exchange between Irish indentured servants and enslaved Africans, starting in the 1600s, meaning that this is a dance form that’s been in the making for over 300 years.

“As a person with Appalachian roots, it’s very important to me,” Shepherd-Powell said. “I feel like I can feel the connection through dancing.”

After this demonstration, McKenzie shared a presentation on the history of the banjo, a common instrument in Appalachian music.

“It’s come a long way from its ancestors in Africa. It resembles a lot of instruments from the western part of that continent,” he said.

The most direct ancestor of the banjo would be the akonting, a traditional instrument of the Jola people of West Africa. It is played similarly to the banjo, with a downstroke motion.

One of the earliest depictions of the banjo in America is in a painting done in the late 1700s by John Rose, a slaveholder from Beaufort, South Carolina, called The Old Plantation. According to Jerome S. Handler, writing for the African Diaspora Archaeology Newsletter, it is “arguably the best-known depiction of slaves in America,” and it shows the efforts enslaved people made “to maintain African cultural traditions within the difficult, often hostile context of plantation life.”

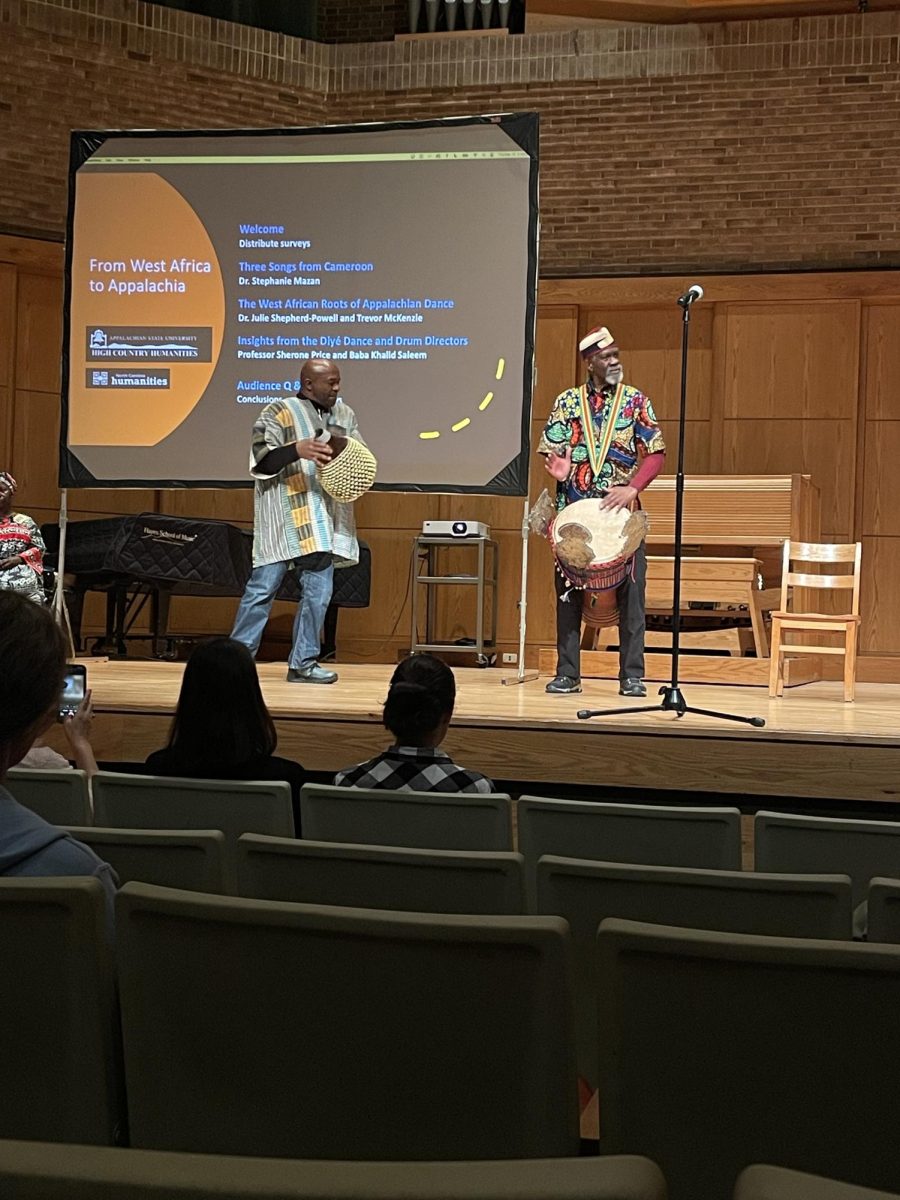

Sherone Price, a professor of African Dance at App State, addressed a variety of dance styles and demonstrated steps accompanied on the drums by Khalid Abdul N’Faly Saleem, instructor of African Drumming for Dance.

Price and Saleem have been dancing and making music together for 40 years. Price said that the beauty of West African and Appalachian dance is that it involves people of all shapes and sizes. He said people can enjoy these cultural dances and pass them on for generations.

“When I talk about the dances, I have to talk about where they came from and how they were used,” Price said. “There’s a word called Sankofa, and Sankofa means to move forward in one’s life. You have to look back to see what’s been done before.”

He shared how the future of dance involves everyone learning from and borrowing from each other.

According to Smoky Mountain Living Magazine, poet Frank X Walker coined the term “Affrilachian” to refer to a unique part of the Appalachian and African American experience.

“The story of Affrilachia is not just told in coal mines, small farms, and small African American hillside hamlets; it’s also told in food, music, spirituality, and many other forms of Appalachian culture that bear the influence of West and Central Africa,” wrote Michael W. Twitty for Smoky Mountain Living Magazine.

The High Country Humanities programming brings the scholarly and creative activities of faculty to broader audiences. “It provides students with co-curricular learning experiences that augment classroom learning,” Gardner said.

The series of talks, workshops, demonstrations and film screenings is supported by a grant from North Carolina Humanities.

“For individuals interested in learning more about rural cultures, we will host several more events between now and September,” Gardner said.

The next event, “Documentary Filmmakers on Interpreting Rural Life: From Appalachia to the World,” will be held at the Appalachian Theatre of the High Country on March 22 from 4:30-6:30 p.m. This event, like the others in this series, is free and open to the public.