With the meteoric rise of widely accessible artificial intelligence programs like ChatGPT and BingAI, using AI to cheat has never been easier for students. Despite the initial academic panic regarding AI, professors at App State have started finding their own ways of adapting to the rise of artificial intelligence as the end of the fall semester approaches.

When ChatGPT released nearly a year ago, its use of natural language processing to produce human-like accurate responses instantly triggered a debate among the academic community, with some educators seeing the potential benefits of the technology and others seeing it as a potentially large threat of misinformation.

One year later, some App State professors are optimistic about their responses to and even their use of ChatGPT and other similar technologies, while others are more wary about its implications.

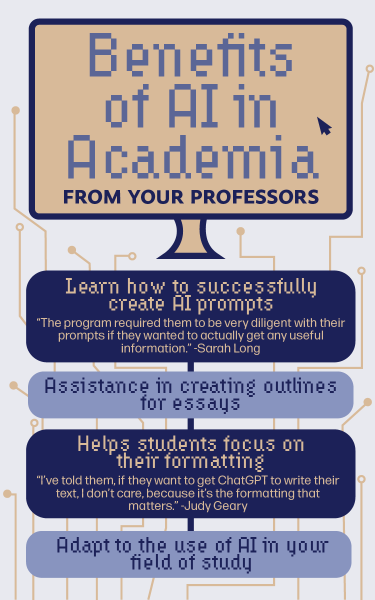

“I actually built my classes this semester in response to AI, and I encourage my students to use it for some of their projects,” said Sarah Long, a professor of computer science technical writing for the Department of English at App State. “They got really excited at first, but what they found out was that the program required them to be very diligent with their prompts if they wanted to actually get any useful information.”

Long said in order to get programs like ChatGPT to provide a proper answer for classes like hers, students need to already be familiar with the content they’re asking for to some extent.

“They need to know how to organize an essay, they need to know how to determine the accuracy of a source, they need to know all of that before they can actually create prompts that will guide GPT in giving them useful outputs,” Long said.

Much of what Long said in favor of ChatGPT was due to the apparent flaws when using the program for advanced purposes. She described a time when her class did a group experiment with ChatGPT to try to have it write an essay for them, only to receive a product that “looked more like an outline than a full essay,” with the output containing no direct quotes from relevant sources and using incorrect citations.

While Long has a more positive view of the potential of AI in a classroom setting, Department of Communication professor Judy Geary took a much more nuanced approach to addressing AI in her syllabus.

“I’ve told them, if they want to get ChatGPT to write their text, I don’t care, because it’s the formatting that matters,” said Geary when referring to her media publishing class. “So in that way, the thing that would upset me if I were teaching public speaking or English, where I’m asking them to create content, isn’t really an issue with what I’m currently teaching.”

Geary’s stance allows and even encourages the use of AI with more format focused classes like media publishing, whereas more content focused classes like public speaking would require her to take harsher stances on AI usage in that context.

“I taught a section of public speaking back in the spring, when AI was first being released to the public,” Geary said. “And I realized that, out of the 20 speeches given for the first assignment, four of them sounded very similar to each other and were, to the minute, the exact length they were supposed to be according to the rubric.”

Though some professors across campus have a semi-positive opinion on how they would address AI in the classroom, Department of Computer Science professor Mitch Parry, who has studied the use of AI and is knowledgeable about the inner workings of ChatGPT, took a stance that is as cautious as it is optimistic.

“I’ve talked to students who are keen on using chat GPT to help them with programs and trying to figure out a good way to prompt ChatGPT or something else like it to help them write code,” Parry said. “I don’t have any proof, but I think it’s detrimental to learning the fundamentals of programming. Often what ChatGPT will spit out is something that looks like a working program, but it may not be. And you’d have to be an expert to tell the difference, and that’s a scary place to be.”

When describing how ChatGPT works compared to the kinds of AI that he teaches, Parry said that the main difference is with scale, saying that ChatGPT is much more complex in terms of its code compared to what he teaches his students.

“Scale is the huge thing. I mean, ChatGPT, we couldn’t afford to house it locally even if we wanted to,” Parry said. “What I do in my classes is to teach the concepts and to teach them how to build these technologies from scratch. There’s no comparison.”