Last semester, now sophomore dance major Hailey Costar excitedly waited backstage as she prepared to perform an independent dance project in Varsity Gym. She quickly reviewed choreography as a way to distract herself and noticed supportive words of encouragement from family and friends wishing her good luck.

She knew some of her friends were attending, but did not expect the audience to be large. She was simply grateful for any opportunity to perform. When she was finally on stage and the lights came up, Costar was able to see how full the room was with people. Attendees ranged from fellow students to faculty all waiting to support her and the other dancers who put work into the showcase.

Brooke Starets, a senior dance major, choreographed the duet that Costar performed in. Starets said one day Costar came to rehearsal dressed in a fully pink outfit. Starets and the other dancer quickly noticed Costar’s socks also added a pink element to the outfit with the ballet shoe design they displayed.

“It made us three laugh, but also was so telling of Hailey’s character: a put-together, color coordinated, spunky ray of sunshine,” Starets said.

Costar said Starets valued both of her cast members’ thoughts and ideas, which was a quality that she was not used to having in a choreographer. Because rehearsals for Starets’ independent project were collaborative and fun, it reminded Costar of her love for performing.

“I think that’s been a very common theme in my dance journey, being the overreacher, the one who wants to shine,” Costar said. “It’s been part of my struggles, but also part of my success.”

Costar has been dancing since she was 3-years-old. She said her parents knew they wanted to put her in dance classes because as soon as she started walking, she always walked on her tiptoes.

“Even at a young age, I was still practicing,” Costar said. “My mom would put together cookbooks so I could tap on my wood floors without ruining them.”

In sixth grade, Costar joined her studio’s competitive team. However, once she was on the team, Costar said she lost some of her love for the art. She saw a decline in the growth of her abilities and technique because of this.

“I felt like because I had been praised when I was younger, I didn’t need to work as hard,” Costar said. “I’ve later learned that is so wrong to think.”

While on the competitive team, Costar said she developed a lot of anxiety surrounding dance. She began comparing herself to her peers, and because she wasn’t progressing at the same rate as them, it only contributed to her self-doubt.

“I thought it was all basically my appearance,” she said. “I thought if I didn’t look like them, I could never dance like them.”

Costar’s anxious mindset led her to develop disordered eating. She was professionally diagnosed with anorexia, bulimia and orthorexia. Even at the height of her disorders, she was still dancing between four to five hours a day, and she said dance became the only thing she was living for.

“I was dancing in a group of middle school girls, which means everybody, for the most part, had something,” Costar said. “One girl had been hospitalized a few times for different mental health things; a few girls would come in and out of class kind of based on the week.”

According to the National Library of Medicine, 12% of dancers will experience some sort of disordered eating within their career. In comparison, the National Association of Anorexia Nervosa and Associated Disorders reports that 9% of the world population is affected by disordered eating.

Costar said despite the fact that she knew others were struggling, she still felt very alone because she was the only person who actually looked sick.

Because her disordered eating affected her appearance and how her dancing looked, it became a harsh cycle that was difficult to escape.

When she finally started to get treatment, the COVID-19 pandemic prevented it from happening in person. Although her in-person treatments stopped, Costar said taking online dance classes was a big part of her recovery and finding a healthy way to love dance.

“All I would do during the day was take these online classes,” she said. “I think I took, like, six hours a day because I realized how much I needed it.”

Coming out of the pandemic, Costar was ready to get back to dancing in person. Unfortunately, her eagerness for participating in class subjected her to being bullied by the same peers she previously compared herself to.

“I was just so happy that I found dance again that I was almost annoying to them,” she said.

However, the bullies were not limited to her fellow students. Her teachers also contributed to the negativity. When she was trying her best in classes, Costar said her teachers said things like “you’re taking up too much space,” and “you need to tone it down.” Costar said it was always condescending, and it got to the point where she was either being placed behind the tallest girl in class or being removed from pieces completely.

“I would leave after rehearsals at the studio crying,” Costar said. “I was told I would never have thin, long dancer legs because I’m a whopping 4-foot-10.”

Because her studio experience turned so negative, Costar said she was ready to come to college with a clean slate.

At the beginning of the 2023 spring semester, Costar auditioned for the Spring Appalachian Dance Ensemble. She wasn’t selected as a cast member, which she said led her to question her belonging as a dance major. Costar said that when Starets casted her in the independent project, “it was like wiping the tears away.”

“The fact that I was chosen made me feel like, ‘Okay yeah, I can do this,’” Costar said.

Although Costar’s height and passion were viewed as weaknesses in the past, Starets said they were both things she celebrated. Because of what she wanted to portray in her independent project, Costar’s height, along with her “soul and skill,” were big contributing factors that led to Starets’ decision to cast her.

“She took her change in plans and ran with them and put her all into my independent project,” Starets said. “I could tell that being in this independent project was something that made her happy.”

Costar said that in her interpretation, the piece was about the battle of having something new but not wanting to let go of the past. She also said that she feels as though the meaning aligns with her experience of coming to App State’s dance department and letting go of her old studio.

“Sometimes as a freshman, the thing that will make you grow the most is simply doing something that makes you happy in a new environment,” Starets said.

Sherone Price, a dance professor at App State, taught Costar in four classes her freshman year, two per semester. Costar said that before coming to App State, her dance teachers would disregard proper technique if it meant seeming more impressive, but Price always encourages the proper way of doing things in order to grow. Costar also said Price has become a major inspiration for her in regards to teaching.

“Something I love about his class is his energy,” Costar said. “He comes in ready to work every single class, and I think that is definitely how it should be.”

Similarly, Price said he has always valued Costar’s lively attitude, and that he appreciates her work ethic.

“She brings a lot of energy to class,” Price said. “She comes in with a big smile on her face no matter what the situation is, which I find very impressive.”

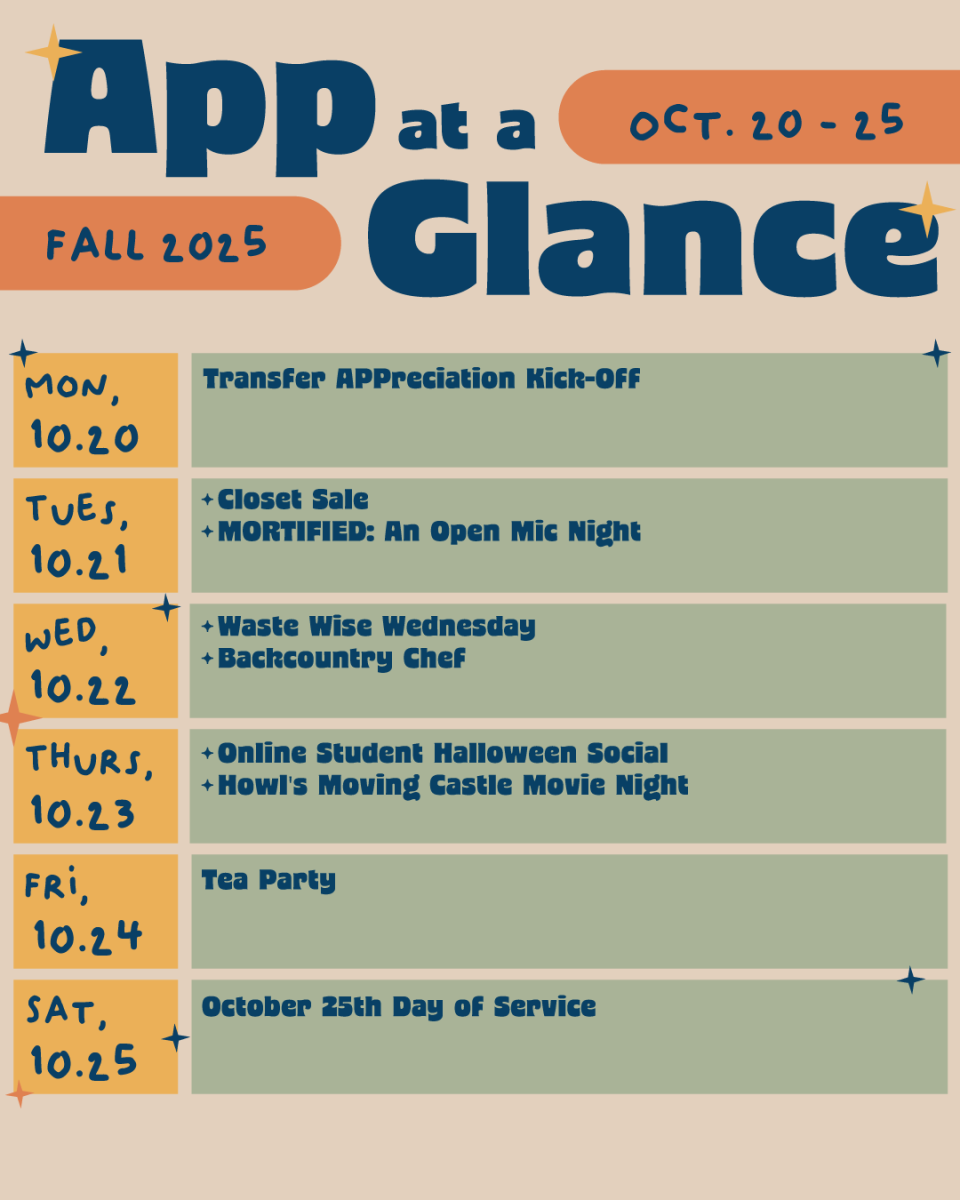

This year, when Costar auditioned for the Fall Appalachian Dance Ensemble, the results turned out quite different. She was cast in not one, but two pieces. Although there were scheduling conflicts with one piece, Costar said she was extremely honored at the prospect of being considered for both and looks forward to dancing on the main stage in Valborg Theatre. Performances will take place Nov. 15-19.

She said that when auditions for SADE took place, she believes she was over-compensating and in a worse mindset that affected the way she came across as a dancer.

She also mentioned that being a part of Starets’ piece helped her get out of her head, and so at this semester’s auditions, she didn’t feel as though she had something to prove: she just wanted to have fun.

“By being in tune with myself and not pushing myself to be a dancer that I’m not, I feel like I was more genuine,” Costar said. “I felt like I was dancing for me.”

Despite the initial disappointment and let down of not being cast in SADE, Costar said she was grateful for the opportunity to grow from the experience. She learned a lot from finding a new place in the dance department, and hopes that her story can be encouraging to others.

“Just know that if you don’t get this show, you’re going to get another one,” she said. “It’s going to work out, even if it’s not the way you wanted it to.”

After graduation, Costar hopes to move straight to New York to begin performing and taking classes with professionals. Post-performance career, she plans to open her own studio to create the welcoming environment she wishes she had. She also hopes to one day make it a non-profit, so that dance can reach people who normally wouldn’t be financially fit to participate.

Body dysmorphia, being bullied and rejection can be common experiences for people in the dance community. What sets a dancer apart is not having faced that adversity, but how they chose to respond to it. Through each of her struggles, Costar’s passion for dance never faded. Instead, she plans to use that passion to do good within the community.

“I want to make it collaborative, and I want dancers to feel like they can use their voice and their passions because for so long, I wasn’t able to use mine,” Costar said. “I want to show people that you can love dance and have that passion and not be torn down for it.”